|

![]()

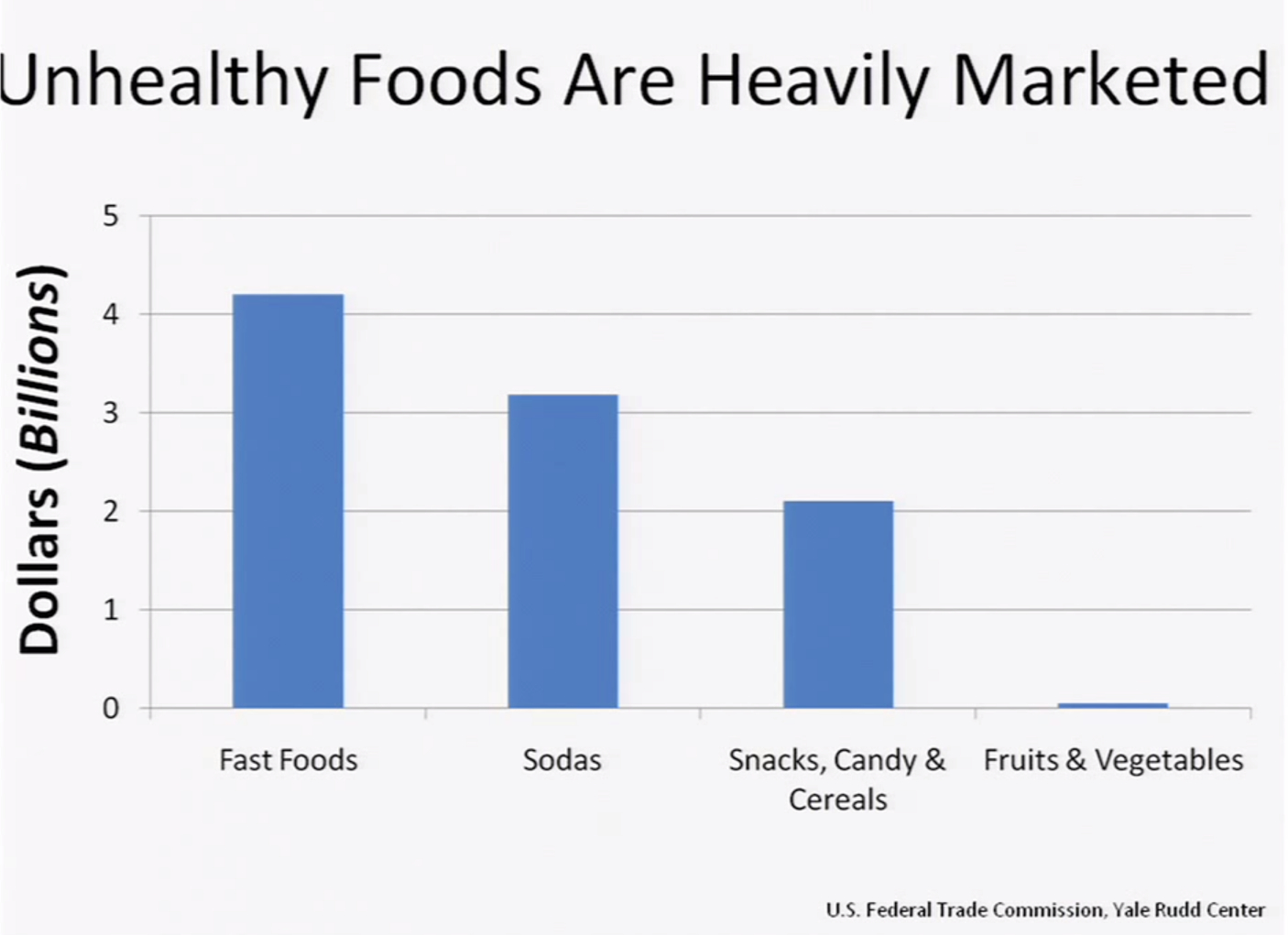

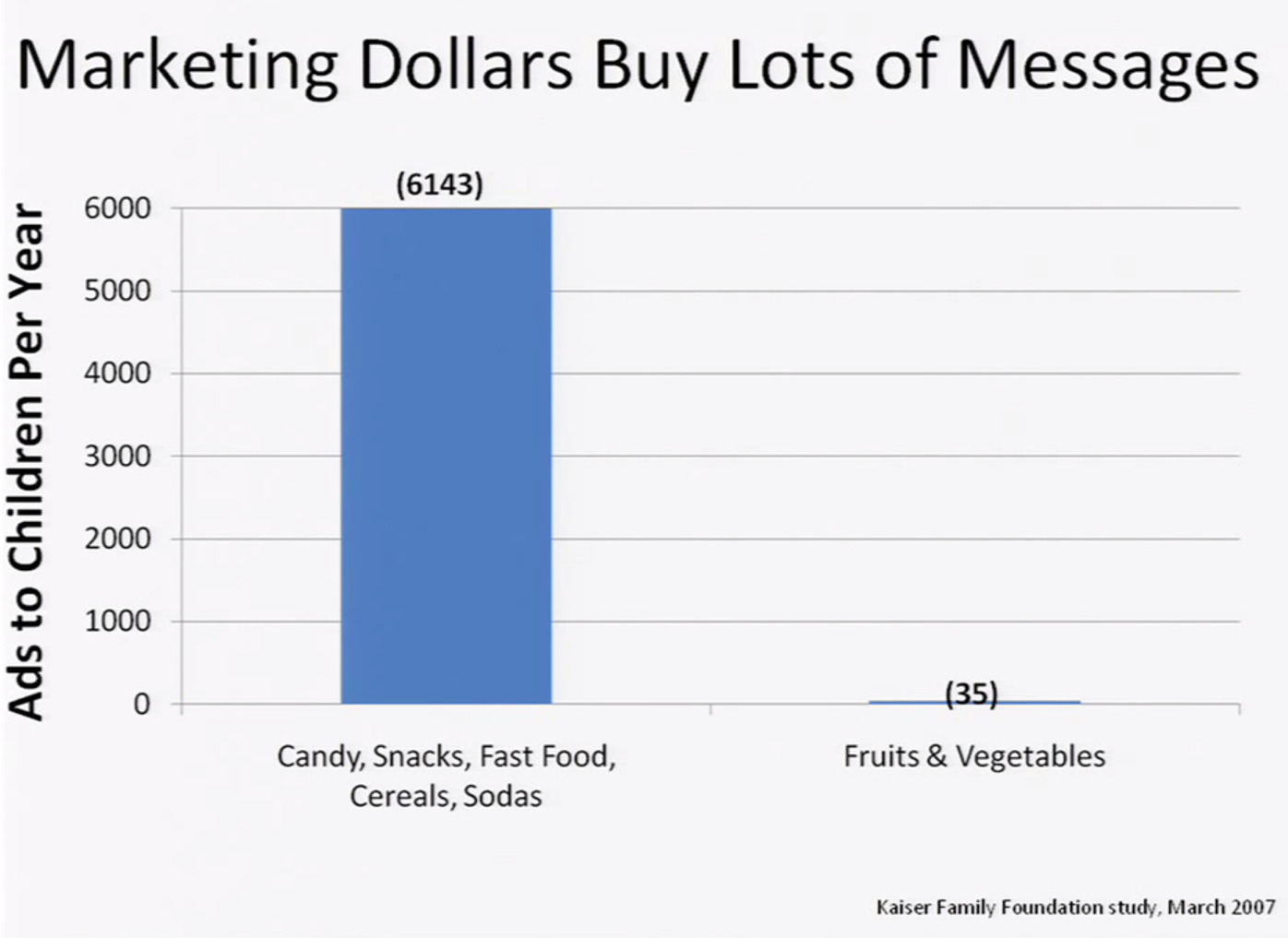

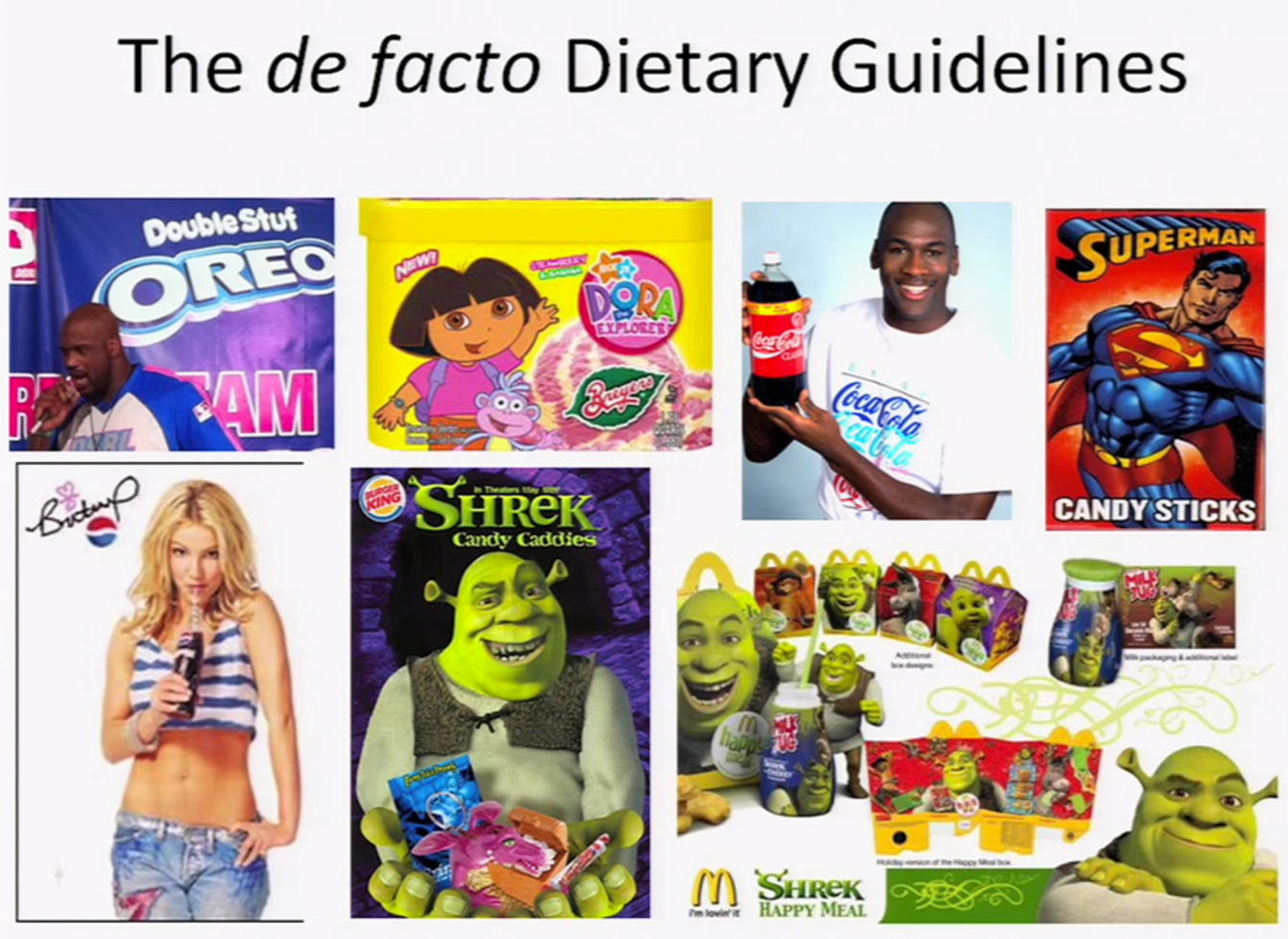

| Advertising and marketing reinforce new eating patterns Why1 #352388 Marketing and advertising instil and reinforce new cultural norms about what (e.g. fast food) and how to eat (e.g. snacking), and how much (e.g. larger portions) to eat. |

Sources: Scott Kahan, U.S. Federal Trade Commission, Yale Rudd Center, Kaiser Family Foundation |

+Citations (5) - CitationsAdd new citationList by: CiterankMapLink[1] The Extent, Nature and Effects of Food Promotion to Children: A Review of the Evidence to December 2008

Author: Georgina Cairns, Kathryn Angus, Gerard Hastings - WHO

Publication info: 2009 December

Cited by: David Price 12:58 PM 6 September 2014 GMT

Citerank: (1) 399917Advertising and marketing reinforce new eating patterns Marketing and advertising instil and reinforce new cultural norms about what (e.g. fast food) and how to eat (e.g. snacking), and how much (e.g. larger portions) to eat.555CD992

URL:

| | Excerpt / Summary In summary, the review confirms that in both developed and developing countries: there is a great deal of food promotion to children. Television advertising is the most dominant promotional channel but the full range of promotion and marketing techniques and strategies are used in, and integrated together, by the food and advertising industries. Children recall, enjoy and engage with the multiple promotions and evocative brand building initiatives they are exposed to. The emergence of new mass media channels such as website and mobile telephone SMS services offer less visible but highly direct targeted marketing opportunities. The evidence base for the effect and reach of these newer promotional channels is quite small, but to date, suggests it is gaining share rapidly and effectively.

The evidence reviewed confirms that the food products promoted continue to represent a very undesirable dietary profile, with heavy emphasis on energy dense, high fat, high salt and high sugar foods, and almost no promotion of foods that public health evidence encourages greater consumption of – for example fruit and vegetables.

Research that has examined associations between food promotion and food behaviours, determinants of behaviour and diet-related health outcomes, finds modest but consistent evidence that the link is causal. This evidence base is drawn from research conducted in the developed world. It is however, reasonable to assume these findings can be extrapolated to low and middle income countries because the research on extent and nature of promotion to children confirms that marketing activity in poorer countries mirrors the activity in more affluent economies. Furthermore, there is evidence that children in emerging markets are targeted both directly as consumers and as a bridgehead to wider society experiencing rapid cultural change. There is also a possibility that with a shorter history of exposure to sophisticated marketing techniques and less regulated marketing controls, children in developing and emerging economies may be more susceptible to the persuasive influences of food marketing and promotions. |

Link[3] Overcoming policy cacophony on obesity: an ecological public health framework for policymakers

Author: Tim Lang, Geoff Rayner

Publication info: 2007, Obesity Reviews 8 (Suppl. 1): 165.

Cited by: David Price 1:33 PM 6 September 2014 GMT

Citerank: (21) 348675Adopt a whole systems approach to obesityTackling obesity effectively—accomplishing a population wide-shift—requires a comprehensive and integrated whole systems approach, involving a range of measures focusing on individuals, social and other systems, including at the local and community level, and on the interrelated physical, physiological, social and cognitive factors that determine health outcomes.565CA4D9, 348693Stakeholders – Groups & ActionsExplore the map via the different stakeholder groups and the measures each group can take to help tackle the obesity crisis.58D3ABAB, 348702Individuals and FamiliesThe actions and choices of individuals and families are fundamental to the challenge of tackling obesity. 84E4A378, 348703Actions – Industry2794CAE1, 348780Causes of obesityUnderstanding the causes of obesity is critical to the success of prevention and treatment strategies. However, while (simply put) obesity occurs when energy intake from food and drink consumption is greater than energy expenditure through the body’s metabolism and physical activity over a prolonged period (resulting in the accumulation of excess body fat), in reality many complex behavioural and societal factors contribute systemically to the current crisis and no single influence dominates.555CD992, 352281Changes required across many different policy areasObesity has to be seen as not just a technical, food, physical activity or healthcare problem but a challenge for what sort of society is being built. Small, incremental, publicity-driven (i.e. social market-based) changes might suit the existing balance of policy interests, but a more extensive, co-ordinated, cross-sectoral action would be more effective.1198CE71, 352314Actions – Central Government2794CAE1, 352387Previous physical activities replaced by industrially generated energyIndustrial development allows many different aspects of life that previously involved daily physical activity to be accomplished through industrially generated energy instead; for example, the substitution of motorised transport for walking and cycling, a shift from manual and agricultural work towards office work, and a multitude of labour saving devices at work and in the home.555CD992, 352389Reluctance to talk about and address implications of own weightThe weight of the population continues to rise despite media imagery of thin models encouraging a slim ideal that is far out of reach for most of the public. In this context, “Fat” remains an emotive and stigmatic subject – and often perceived as an insult – which makes it harder for people to acknowledge, confront and address their own obesity (and harder for others including health professionals to encourage them to do so too).555CD992, 352391Industrial development changes what and how people eatEconomic and industrial development has tended to be accompanied by a historic shift in patterns of food consumption from diets high in cereal and fibre to diets high in sugars, fat, animal-source food and highly-processed foods – creating a socio-cultural environment in which obesity is more likely to emerge in the population.555CD992, 352399Successive governments have made counterproductive policy choicesThe growing prevalence of obesity in the UK is partly the result of well-intentioned but counterproductive policy choices made by successive governments over several decades.555CD992, 352400Many individuals are consuming more energy than they are expendingPublic Health England estimates that the average man in England is consuming around 300 calories a day more than they would need were they a healthy body weight.555CD992, 399547Adopt a whole systems approach to obesityTackling obesity effectively—accomplishing a population wide-shift—requires a comprehensive and integrated whole systems approach, involving a range of measures focusing on individuals, social and other systems, including at the local and community level, and on the interrelated physical, physiological, social and cognitive factors that determine health outcomes.565CA4D9, 399558Changes required across many different policy areasObesity has to be seen as not just a technical, food, physical activity or healthcare problem but a challenge for what sort of society is being built. Small, incremental, publicity-driven (i.e. social market-based) changes might suit the existing balance of policy interests, but a more extensive, co-ordinated, cross-sectoral action would be more effective.1198CE71, 399887Causes of obesityUnderstanding the causes of obesity is critical to the success of prevention and treatment strategies. However, while (simply put) obesity occurs when energy intake from food and drink consumption is greater than energy expenditure through the body’s metabolism and physical activity over a prolonged period (resulting in the accumulation of excess body fat), in reality many complex behavioural and societal factors contribute systemically to the current crisis and no single influence dominates.555CD992, 399890Successive governments have made counterproductive policy choicesThe growing prevalence of obesity in the UK is partly the result of well-intentioned but counterproductive policy choices made by successive governments over several decades.555CD992, 399891Many individuals are consuming more energy than they are expendingPublic Health England estimates that the average man in England is consuming around 300 calories a day more than they would need were they a healthy body weight.555CD992, 399896Industrial development changes what and how people eatEconomic and industrial development has tended to be accompanied by a historic shift in patterns of food consumption from diets high in cereal and fibre to diets high in sugars, fat, animal-source food and highly-processed foods – creating a socio-cultural environment in which obesity is more likely to emerge in the population.555CD992, 399907Reluctance to talk about and address implications of own weightThe weight of the population continues to rise despite media imagery of thin models encouraging a slim ideal that is far out of reach for most of the public. In this context, “Fat” remains an emotive and stigmatic subject – and often perceived as an insult – which makes it harder for people to acknowledge, confront and address their own obesity (and harder for others including health professionals to encourage them to do so too).555CD992, 399917Advertising and marketing reinforce new eating patterns Marketing and advertising instil and reinforce new cultural norms about what (e.g. fast food) and how to eat (e.g. snacking), and how much (e.g. larger portions) to eat.555CD992, 399923Previous physical activities replaced by industrially generated energyIndustrial development allows many different aspects of life that previously involved daily physical activity to be accomplished through industrially generated energy instead; for example, the substitution of motorised transport for walking and cycling, a shift from manual and agricultural work towards office work, and a multitude of labour saving devices at work and in the home.555CD992 URL:

| | Excerpt / Summary There are many competing diagnoses of what ‘really’ matters in obesity generation. Different analyses and policy solutions have been developed and proffered, each clamouring for support, funding and adoption. The increasing sophistication of different positions actually adds to the complexity of the policy challenge. For policymakers, now worried about the cost of obesity (and the spectrum of ailments linked to it, such as diabetes), there is a situation we describe as policy cacophony – noise drowning out symphony of effort. This cacophony is not helpful because policymakers need coherent directions on which they feel they can deliver. Obesity policy is already weighed down by complexity, accentuated by the multi-level (global, European, national, regional and local) nature of modern systems of governance. It is also shrouded by ideological fears such as interventions being interpreted as ‘nanny-ish’ or restricting ‘personal’ choices in food and lifestyle.

Compounding this policy cacophony are two other difficulties which this review sets out to address. The first is time frame. Obesity is a problem that has taken decades to develop. Bar sudden external shocks to society, such as a massive oil shortage or price rises that make walking a necessity, it is likely to take many years to bring it under control. Yet, the political timetable demands quick results. Second, there is a difficulty about evidence. No country has managed to reverse obesity trends, or at least not so far. To some extent, part of the obesity policy problem is the evidence, or lack of it. Yet, the rise of obesity is literally visible and the explanation and ways forward are hard to pinpoint. This does not mean we favour disregarding evidence, but rather that we see obesity as a test case for policy changes in advance of perfect evidence. Faint hearts privately muse that obesity is too complex. But we see obesity as akin to that of climate change – complex, yes – and demanding firm action, however hard that might be. |

Link[4] Why we eat the way we eat

Author: Scott Kahan

Publication info: 2011 June, 3

Cited by: David Price 10:13 AM 17 December 2014 GMT

Citerank: (15) 352390Industrial way of life is obesogenicRapid societal changes—for example, in food production, motorised transport and work/home lifestyle patterns—have placed human physiology (which has evolved to cope with an under-supply of food and high energy expenditure) under new stresses, and revealed an underlying genetic tendency to accumulate and conserve energy (i.e. gain weight) in a high proportion of the population. In this sense, obesity can be construed as a normal physiological response to an abnormal environment.555CD992, 368175Targeting advertising at childrenAdvertising and other marketing approaches are targeted at children and other vulnerable groups.62C78C9A, 370363Unhealthy foods are cheaper and getting cheaper555CD992, 370364Portions have grown larger555CD992, 370365Unhealthier foods are engineered to be tastierFood scientists have become adept at understanding how our brains respond to, and react to, and crave tastes, smells and textures, and have become adept at engineering and processing foods to take advantage of that – largely by adding lots of salt, sugar and fat – and to make these foods almost irresistible to our brains.555CD992, 370366Ready-to-eat food is more readily availableReady-to-eat food is increasingly available in industrial societies 24-hours a day and in places where food wasn't traditionally available (such as pharmacies and petrol stations), as well as via the growing number of fast food restaurants and coffee shops.555CD992, 371727Growth in restaurants and dining outThe restaurant industry has almost doubled its share of every dollar spent on food in the United States over the last 60 years from 25% in 1955 to 47% today. Much of this growth reflects the expansion in fast food restaurants (a trend observed in other countries including the UK).648CC79C, 399889Industrial way of life is obesogenicRapid societal changes—for example, in food production, motorised transport and work/home lifestyle patterns—have placed human physiology (which has evolved to cope with an under-supply of food and high energy expenditure) under new stresses, and revealed an underlying genetic tendency to accumulate and conserve energy (i.e. gain weight) in a high proportion of the population. In this sense, obesity can be construed as a normal physiological response to an abnormal environment.555CD992, 399917Advertising and marketing reinforce new eating patterns Marketing and advertising instil and reinforce new cultural norms about what (e.g. fast food) and how to eat (e.g. snacking), and how much (e.g. larger portions) to eat.555CD992, 399918Unhealthy foods are cheaper and getting cheaper555CD992, 399919Portions have grown larger555CD992, 399920Unhealthier foods are engineered to be tastierFood scientists have become adept at understanding how our brains respond to, and react to, and crave tastes, smells and textures, and have become adept at engineering and processing foods to take advantage of that – largely by adding lots of salt, sugar and fat – and to make these foods almost irresistible to our brains.555CD992, 399921Ready-to-eat food is more readily availableReady-to-eat food is increasingly available in industrial societies 24-hours a day and in places where food wasn't traditionally available (such as pharmacies and petrol stations), as well as via the growing number of fast food restaurants and coffee shops.555CD992, 399945Targeting advertising at childrenAdvertising and other marketing approaches are targeted at children and other vulnerable groups.62C78C9A, 399947Growth in restaurants and dining outThe restaurant industry has almost doubled its share of every dollar spent on food in the United States over the last 60 years from 25% in 1955 to 47% today. Much of this growth reflects the expansion in fast food restaurants (a trend observed in other countries including the UK).648CC79C URL: |

Link[5] Influence of licensed spokescharacters and health cues on children's ratings of cereal taste

Author: M.A. Lapierre, S.E. Vaala, D.L. Linebarger

Publication info: 2011 March, Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011 Mar;165(3):229-34. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.300

Cited by: David Price 10:23 AM 17 December 2014 GMT

Citerank: (3) 368175Targeting advertising at childrenAdvertising and other marketing approaches are targeted at children and other vulnerable groups.62C78C9A, 399917Advertising and marketing reinforce new eating patterns Marketing and advertising instil and reinforce new cultural norms about what (e.g. fast food) and how to eat (e.g. snacking), and how much (e.g. larger portions) to eat.555CD992, 399945Targeting advertising at childrenAdvertising and other marketing approaches are targeted at children and other vulnerable groups.62C78C9A

URL: | | Excerpt / Summary > OBJECTIVE: To investigate whether licensed media spokescharacters on food packaging and nutrition cues affect young children's taste assessment of products.

> DESIGN: In this experimental study, children viewed 1 of 4 professionally created cereal boxes and tasted a "new" cereal. Manipulations included presence or absence of licensed cartoon spokescharacters on the box and healthy or sugary cereal name.

> SETTING: Shopping center in a large northeastern city in December 2007.

> PARTICIPANTS: Eighty children (mean [SD] age, 5.6 [0.96] years; 53% girls) and their parents or guardians.

> MAIN EXPOSURE: Licensed cartoon characters and nutrition cues in the cereal name.

> OUTCOME MEASURES: Children rated the cereal's taste on a 5-point smiley face scale (1, really do not like; 5, really like).

> RESULTS: Children who saw a popular media character on the box reported liking the cereal more (mean [SD], 4.70 [0.86]) than those who viewed a box with no character on it (4.16 [1.24]). Those who were told the cereal was named Healthy Bits liked the taste more (mean [SD], 4.65 [0.84]) than children who were told it was named Sugar Bits (4.22 [1.27]). Character presence was particularly influential on taste assessments for participants who were told the cereal was named Sugar Bits.

> CONCLUSIONS: The use of media characters on food packaging affects children's subjective taste assessment. Messages encouraging healthy eating may resonate with young children, but the presence of licensed characters on packaging potentially overrides children's assessments of nutritional merit.

|

|

|