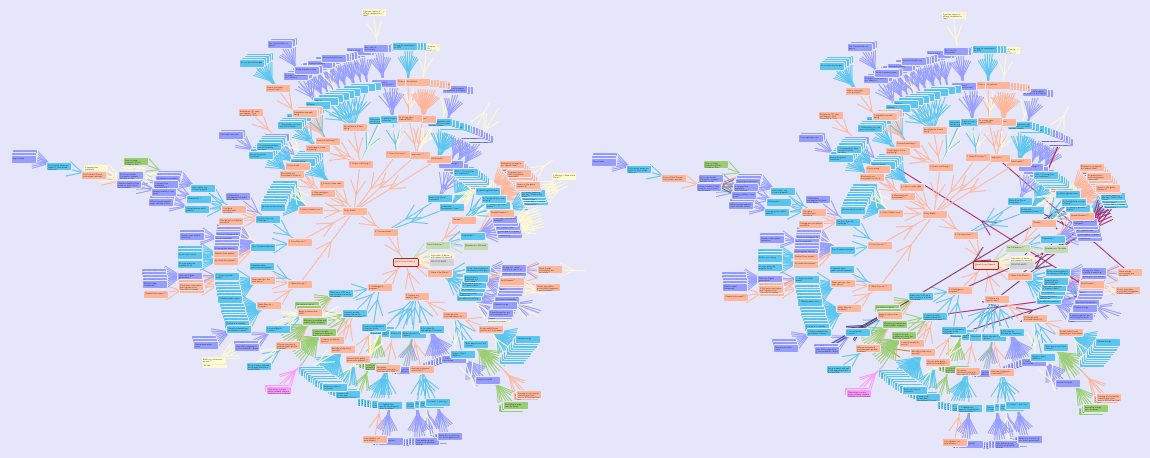

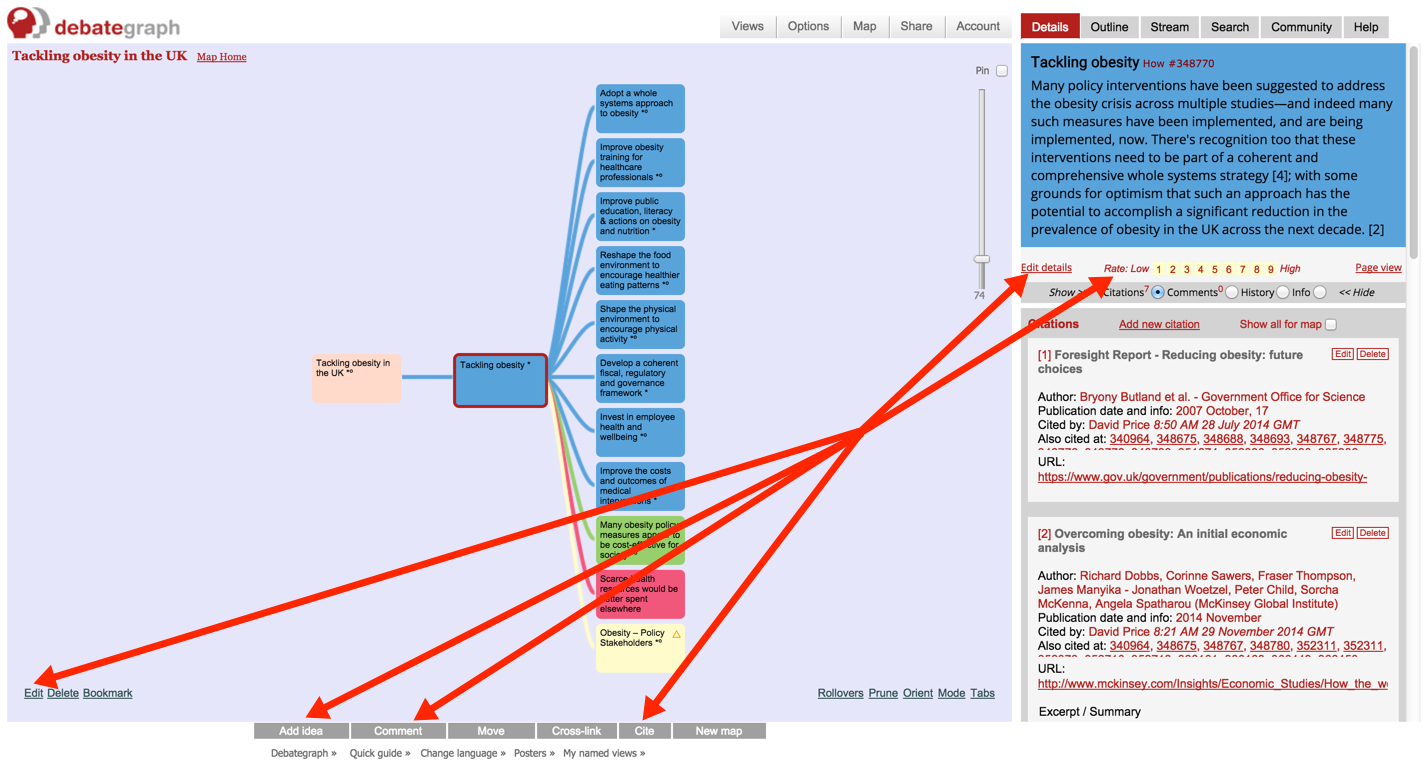

MAP TITLE: Tackling obesity in the UK(Node #340964)With concern growing that the Foresight analysis—that 50% of the UK population could be obese by 2050, at an annual cost to the nation of around £50 billion per year [2]—substantially underestimates the scale of the unfolding obesity crisis, the College of Contemporary Health is working with the wider policy community to develop a whole systems map of the obesity crisis and the potential responses.

Short Link: debategraph.org/obesity Register/log-in

Outline view ›› Document view ›› Radial view ›› Add a Comment or Link ››

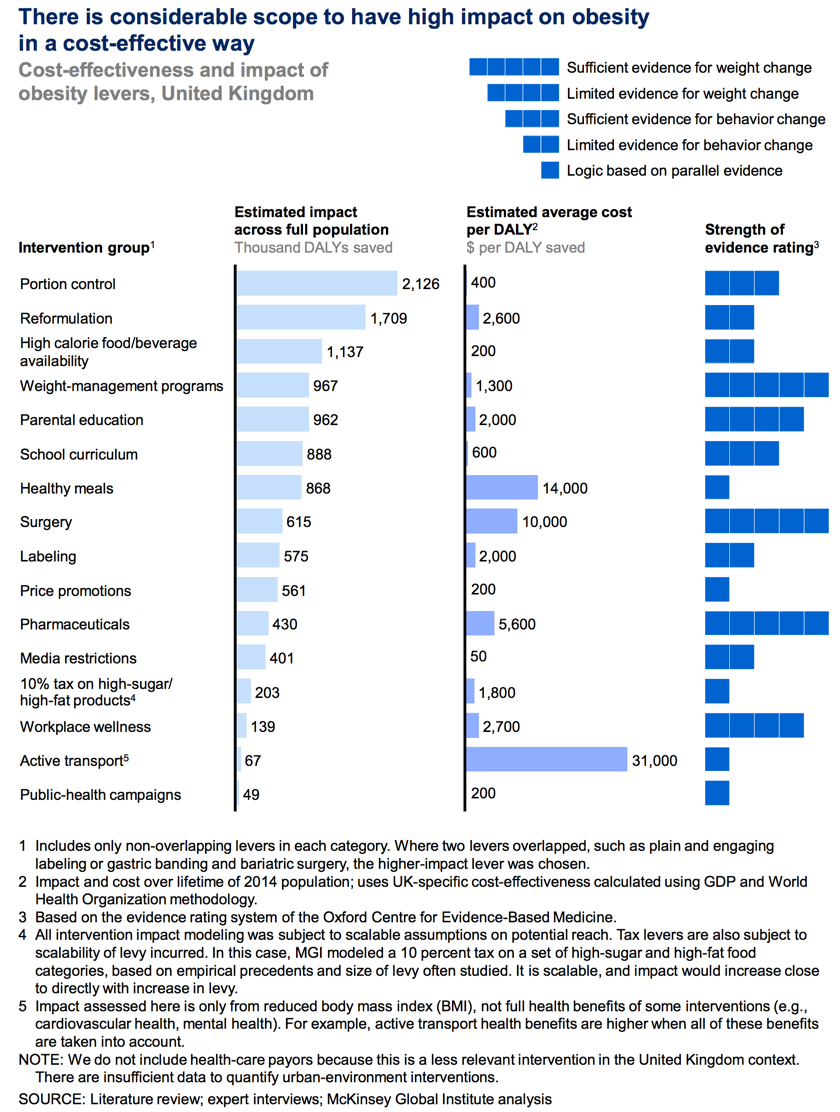

In introducing their excellent recent analysis [7] of the obesity challenge in the UK and beyond, the McKinsey Global Insight authors noted:

...our analysis is by no means complete. Rather, we see our work on a potential program to address obesity as the equivalent of the maps used by 16th-century navigators. Some islands were missing and some continents misshapen in these maps, but they were still helpful to the sailors of that era. We are sure that we have missed some interventions and over- or underestimated the impact of others. But we hope that our work will be a useful guide and a starting point for efforts in the years to come, as we and others develop this analysis and gradually compile a more comprehensive evidence base on this topic.

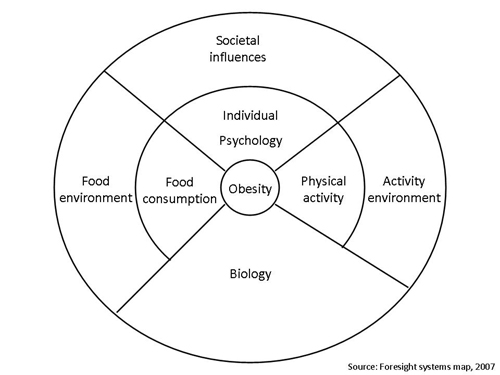

Similarly, the authors of the 2007 Foresight Report [2] engaged in extensive systems mapping work to develop a qualitative, causal loop model to:

- help us understand the complex systemic structure of obesity

- contribute to developing a tool that helps policy makers respond to obesity in the generation, definition and testing of possible policy options.

The obesity mapping project initiated here by The College of Contemporary Health [8] is grounded the same spirit and intent. It aims to create a comprehensive and coherent visual representation of the obesity governance space – including the causes, impacts, policy actors, proposed interventions, evidence, guidance, and barriers to change – that can help each stakeholder explore and understand the space as a systemic whole; that can be collaboratively and iteratively edited, refined, and evaluated by the policy community; and that provides a dynamic, open substrate for dialogue, learning and action across the policy community.

Obesity Mapping Project initiated by The College of Contemporary Health

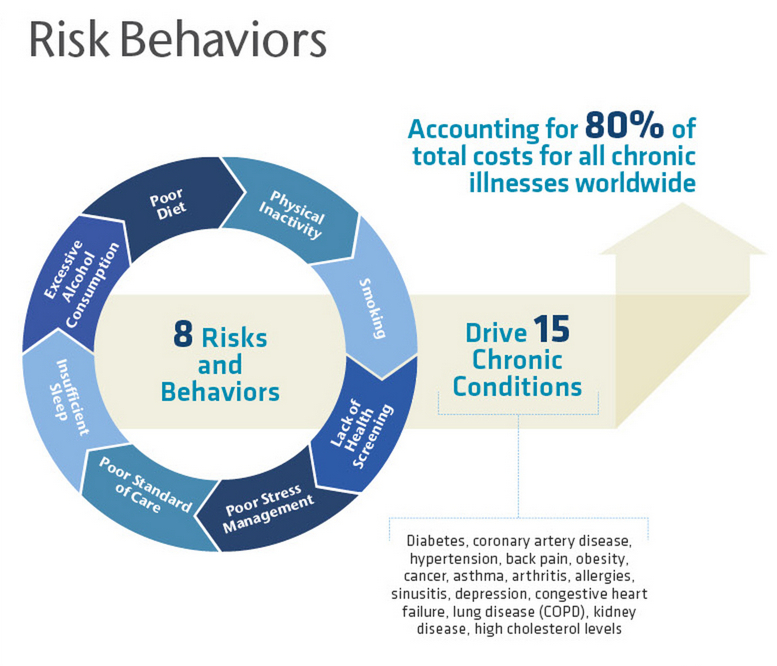

Causes of obesity(Node #348780)Understanding the causes of obesity is critical to the success of prevention and treatment strategies. However, while (simply put) obesity occurs when energy intake from food and drink consumption is greater than energy expenditure through the body’s metabolism and physical activity over a prolonged period (resulting in the accumulation of excess body fat), in reality many complex behavioural and societal factors contribute systemically to the current crisis and no single influence dominates.

View full size >>

The Foresight report [2] refers to a “complex web of societal and biological factors that have, in recent decades, exposed our inherent human vulnerability to weight gain”, and presents an obesity system map (above) with energy balance at its centre and over 100 variables directly or indirectly influencing this energy balance; grouped in 7 cross-cutting themes (below):

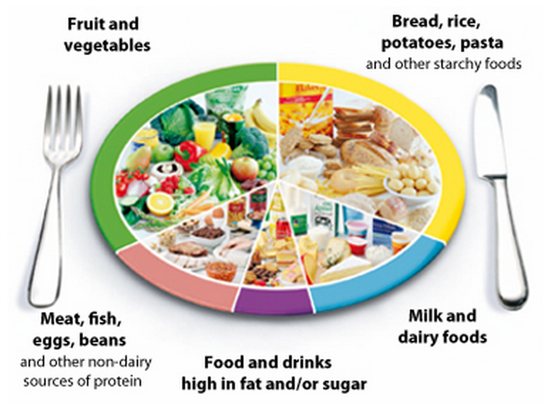

- Biology: an individual's starting point - the influence of genetics and ill health;

- Activity environment: the influence of the environment on an individual’s activity behaviour, for example a decision to cycle to work may be influenced by road safety, air pollution or provision of a cycle shelter and showers;

- Physical Activity: the type, frequency and intensity of activities an individual carries out, such as cycling vigorously to work every day;

- Societal influences: the impact of society, for example the influence of the media, education, peer pressure or culture;

- Individual psychology: for example a person’s individual psychological drive for particular foods and consumption patterns, or physical activity patterns or preferences;

- Food environment: the influence of the food environment on an individual’s food choices, for example a decision to eat more fruit and vegetables may be influenced by the availability and quality of fruit and vegetables near home; and,

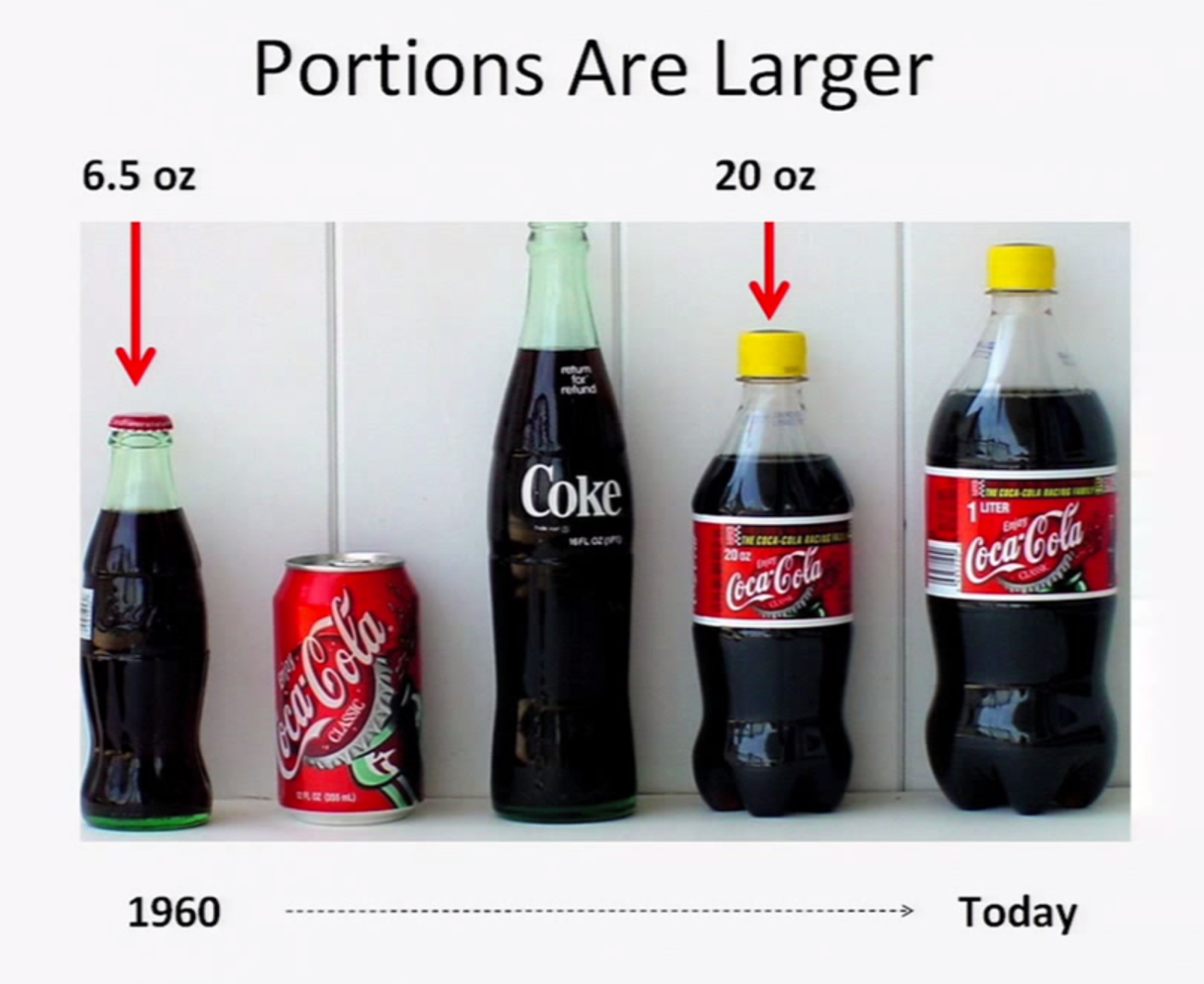

- Food consumption: the quality, quantity (portion sizes) and frequency (snacking patterns) of an individual’s diet.

The Government supports the Foresight view that while achieving and maintaining calorie balance is a consequence of individual decisions about diet and activity, our environment (and particularly the availability of calorie-rich food) now makes it much harder for individuals to maintain healthy lifestyles – and that it is for Government, local government and key partners to act to change the environment to support individuals in changing their behaviour.

Obesity takes time to develop and excess weight takes time to be lost. The risks of becoming obese may also start at an early stage. Growth patterns in the first few weeks and months of life affect the risk of later obesity and chronic disease. There is therefore a life-course component.

Tim Lang and Geof Rayner view the current obesity problem in the UK as the result of ‘societal, technical and ideological change' in the last half-century since the end of World War II and, while acknowledging that the present situation is partially a result of a culture in which highly calorific food is available at pocket money prices and technological advances that have made us a more sedentary nation, note also that:

‘the culture of clever and constant advertising flattering choice; the shift from meal-time eating to permanent grazing; the replacement of water by sugary soft drinks; [and] the rising influence of large commercial concerns framing what is available and what sells’ has powerfully contributed to the growing obesity problem.

Genetic susceptibility to an obesogenic environment(Node #373987)Roughly 70 percent of obesity risk is genetically inherited; however, this genetic inheritance is best understood as a susceptibility to a fattening environment––i.e. in a healthy environment, genes alone do not usually cause obesity: in an unhealthy environment, genetically susceptible people become obese, while others remain lean because they are not genetically susceptible. [1]

- The physical and psychological drivers inherent in human biology mean that the vast majority of people are predisposed to gaining weight. We evolved in a world of relative food scarcity and hard physical work rather than the modern world, where energy-dense food is abundant and labour-saving technologies and sedentary life patterns abound. [5]

- The predisposition (by phenotype) to lay down fat is an evolutionary genetic legacy; with the GAD2 gene (on chromosome 10, human genome) appearing to interact with, and speed up, brain neurotransmitters, which in turn activate part of the hypothalamus, stimulating people to eat more. [6]

- However, moving from a genetic predisposition to obesity itself generally requires some change in diet, lifestyle, or other environmental factors. [7]

Industrial way of life is obesogenic(Node #352390)Rapid societal changes—for example, in food production, motorised transport and work/home lifestyle patterns—have placed human physiology (which has evolved to cope with an under-supply of food and high energy expenditure) under new stresses, and revealed an underlying genetic tendency to accumulate and conserve energy (i.e. gain weight) in a high proportion of the population. In this sense, obesity can be construed as a normal physiological response to an abnormal environment.

"The unhealthiest foods have also become, systematically, the: tastiest, cheapest, largest portion-ed, most accessible, most available, most marketed, and most fun foods." [6]

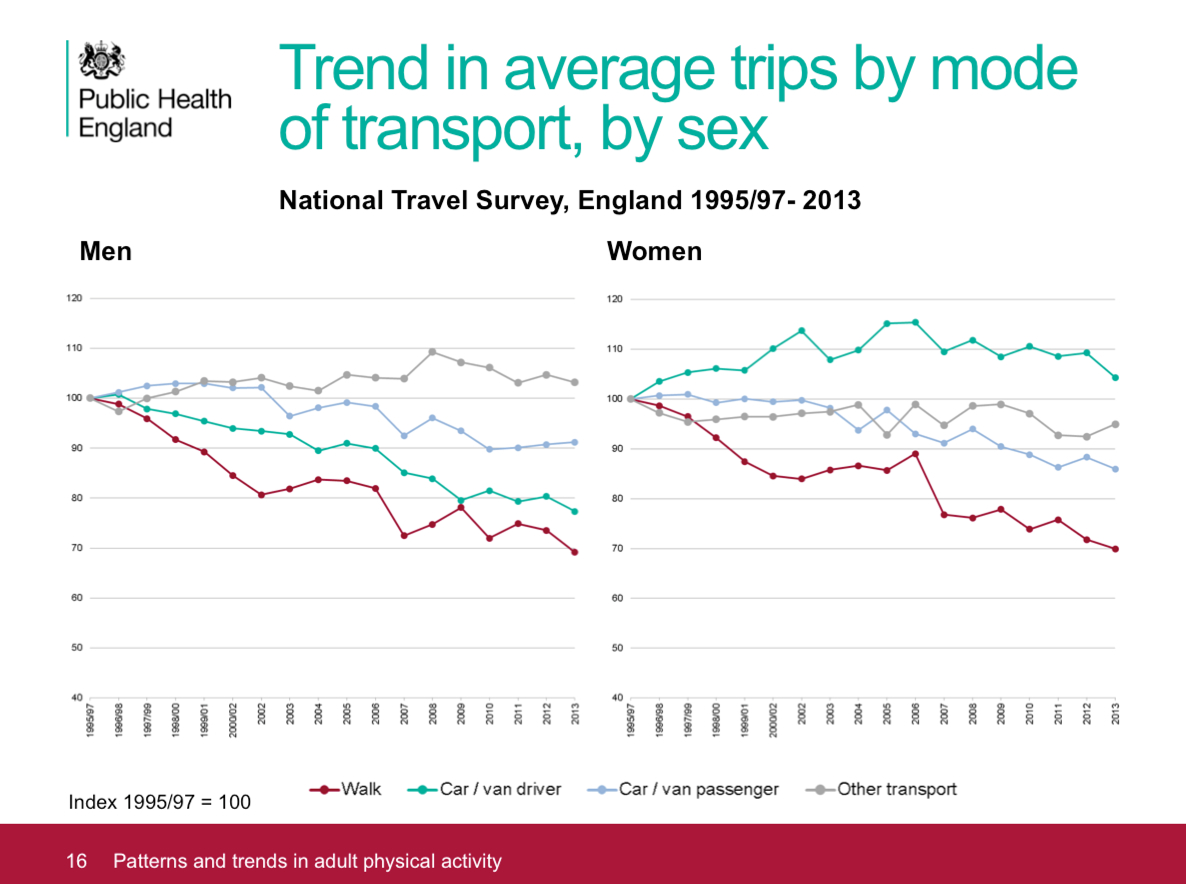

Changing patterns of physical activity(Node #371611)Technological development and urbanisation bring significant shifts in the patterns of daily activity that can reduce the amount of energy people expend in their normal daily routines.

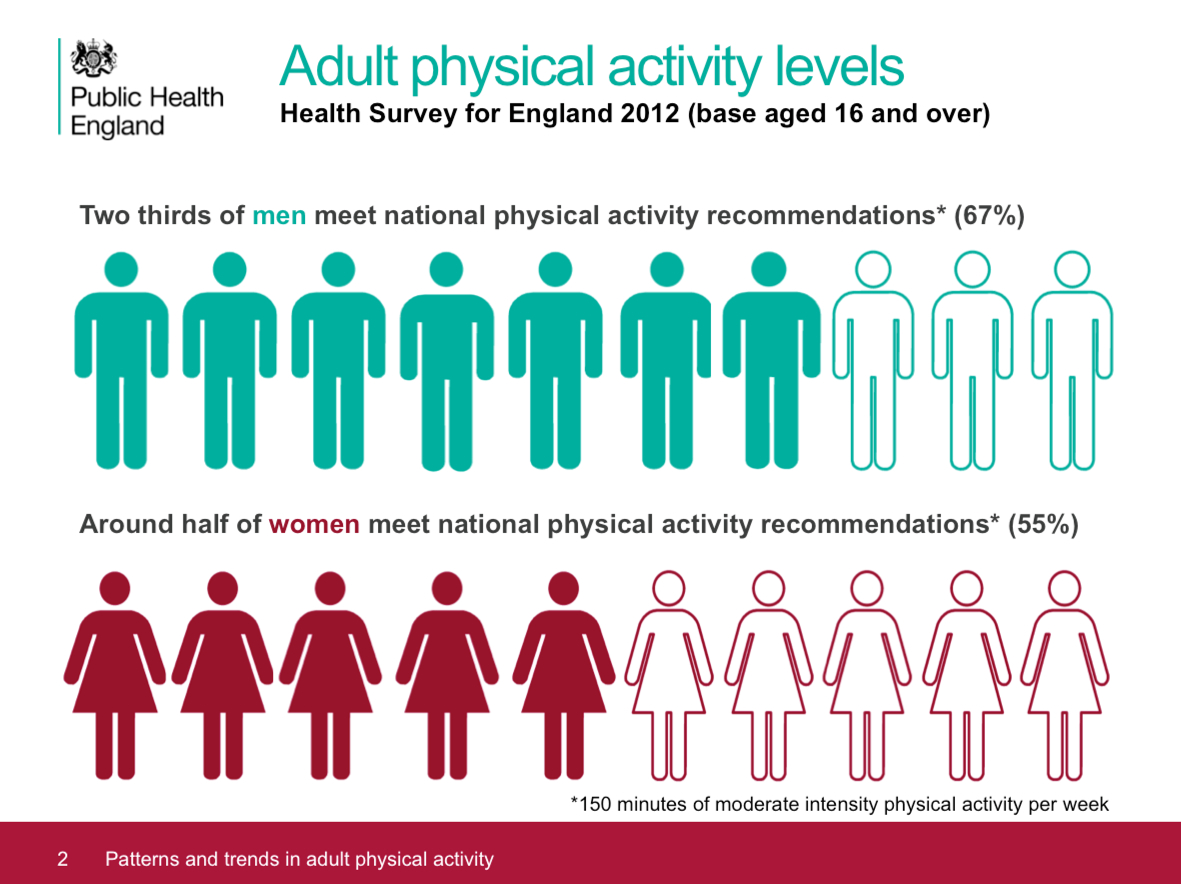

Slides: PHE Adult physical activity slide set – July 2015 [5]Snowdon [6] notes:

If one looks at day-to-day exercise and occupational physical activity, it becomes clear that lifestyles have become more sedentary. The transition from manual labour to office work saw jobs in agriculture decline from eleven to two per cent of employment in the twentieth century while manufacturing jobs declined from 28 to 14 per cent of employment (Lindsay, 2003) [4]. Britons are walking less (from 255 miles per year in 1976 to 179 miles in 2010) and cycling less (from 51 miles per year in 1976 to 42 miles in 2010).

Only 18 per cent of adults report doing any moderate or vigorous physical activity at work while 63 per cent never climb stairs at work and 40 per cent spend no time walking at work (British Heart Foundation, 2012b: 58-59) [3]. Outside of work, 63 per cent report spending less than ten minutes a day walking and 53 per cent do no sports or exercise whatsoever (ibid.: 52-4). Add to this the ubiquity of labour-saving devices and it is clear that Britons today have less need, and fewer opportunities, for physical activity both in the workplace and at home."

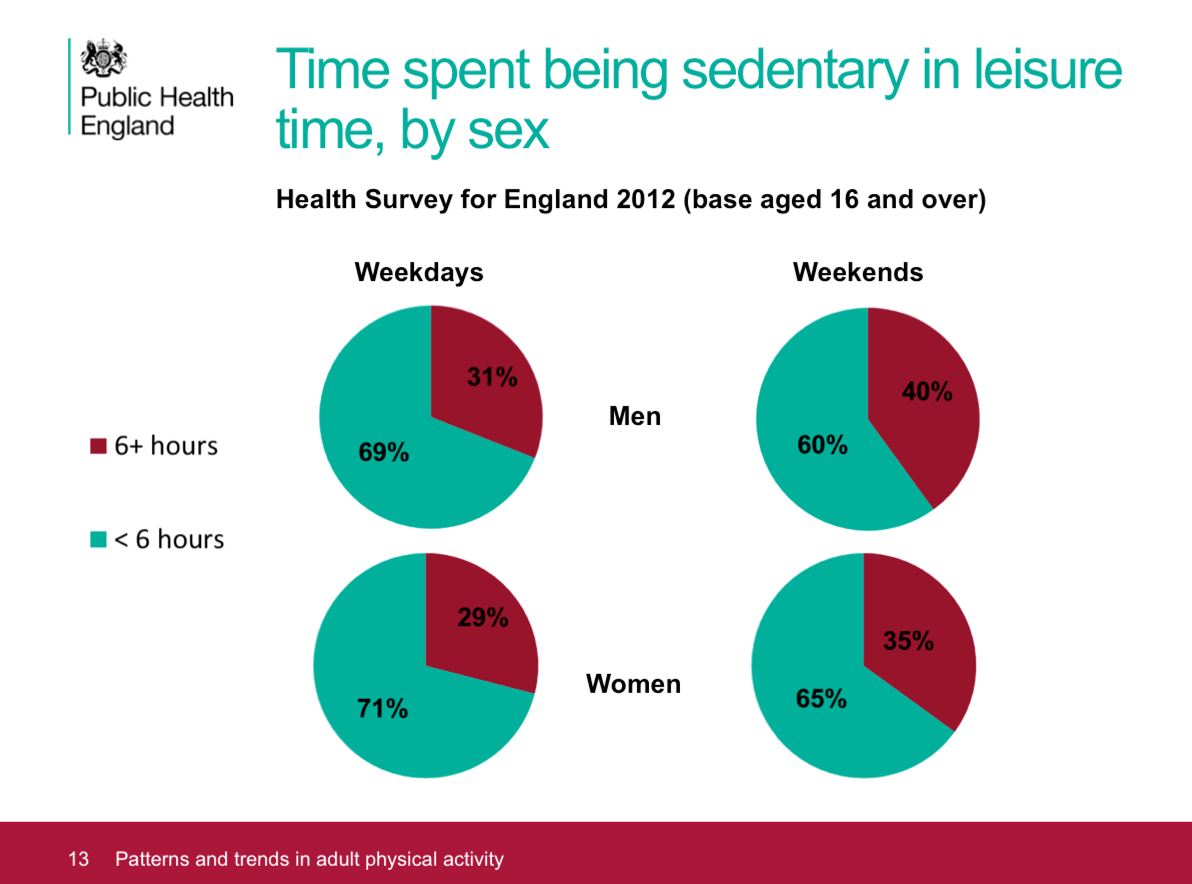

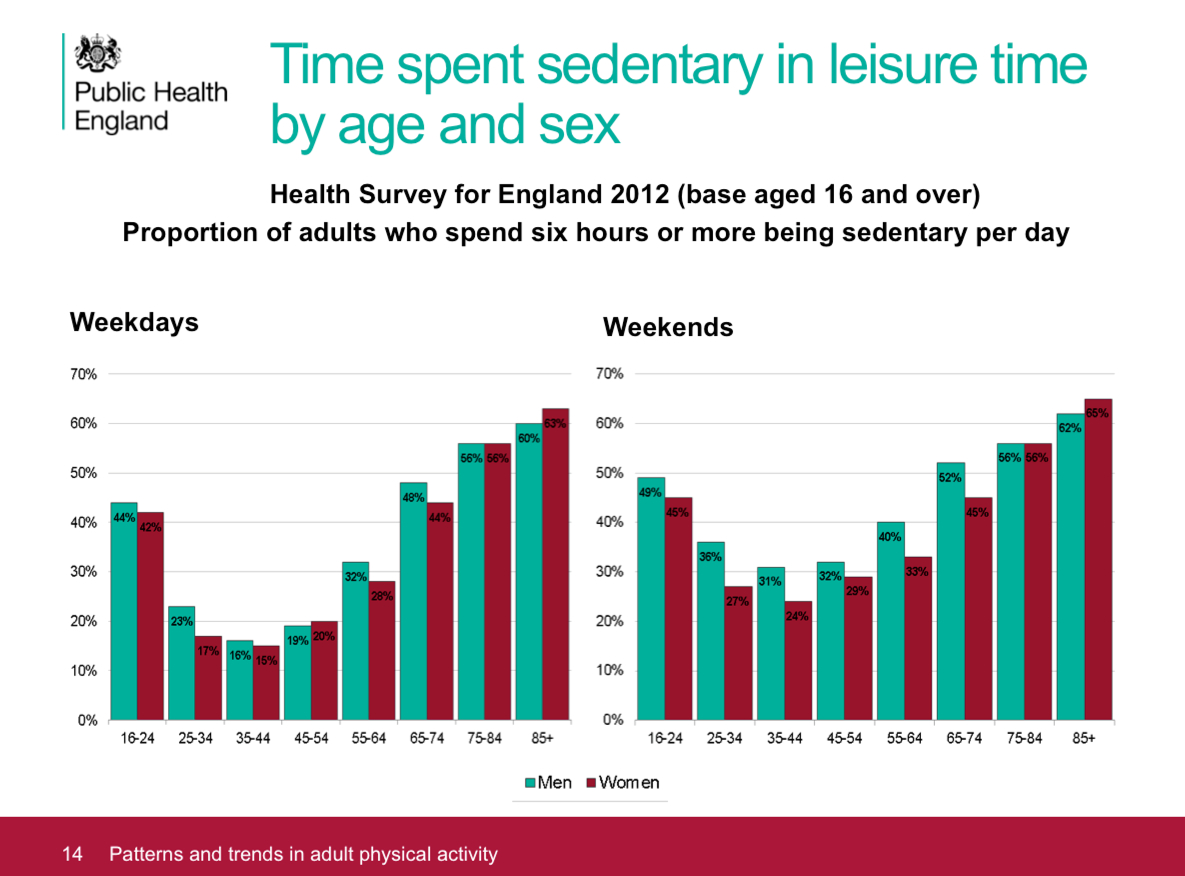

Increasingly sedentary lifestyles(Node #348699)Sedentary behaviour is not simply a lack of physical activity but is a cluster of individual behaviours in which sitting or lying is the dominant mode of posture and energy expenditure is very low. Research suggests that sedentary behaviour is associated with poor health in all ages independent of the level of overall physical activity. Spending large amounts of time being sedentary may increase the risk of some adverse health outcomes, even among people who are active at the recommended levels.

The Sedentary Behaviour and Obesity Expert Working Group [2] noted:

- Researchers have increasingly shown an interest in very low levels of movement and sitting, i.e., sedentary behaviour. While the obvious examples of such behaviours are TV viewing and playing computer games, there are many daily sitting behaviours, including car travel, socialising, reading, and listening to music, as well as long periods spent sitting at school or work. It is all of these sedentary behaviours that are of interest to health researchers and policy makers.

- However, the rise in the interest in sedentary behaviours is closely associated with the rapid increase in the availability and attractiveness of a wide range of screen-based behaviours, including school/work use of computers, leisure time computer use (games, online shopping, internet surfing etc), and TV viewing. While some of these behaviours will have replaced other sedentary pastimes (e.g., radio, reading) over the years, there is widespread belief that the ubiquitous nature of screens is a threat to health from the point of view of very low energy expenditure and hence a risk to the development of overweight and obesity.

Slides: PHE Adult physical activity slide set – July 2015 [5] TV viewing and obesity(Node #352523)

There’s strong evidence that the more television adults and children watch, the more likely they are to gain weight or become overweight or obese.

Previous physical activities replaced by industrially generated energy(Node #352387)Industrial development allows many different aspects of life that previously involved daily physical activity to be accomplished through industrially generated energy instead; for example, the substitution of motorised transport for walking and cycling, a shift from manual and agricultural work towards office work, and a multitude of labour saving devices at work and in the home.

Slides: PHE Adult physical activity slide set – July 2015 [5] Industrial development changes what and how people eat(Node #352391)

Economic and industrial development has tended to be accompanied by a historic shift in patterns of food consumption from diets high in cereal and fibre to diets high in sugars, fat, animal-source food and highly-processed foods – creating a socio-cultural environment in which obesity is more likely to emerge in the population.

Chronic stress(Node #371614)

The chronically stressful patterns and challenges of modern industrial life trigger bio-physical changes in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal system, which, in combination with more energy being consumed than expended, appear to be a contributor to the increased risk for obesity, especially upper body obesity, and other metabolic diseases.

Reduced sleep(Node #371707)Emerging evidence suggests that people who get insufficient sleep have a higher risk of weight gain and obesity than people who get seven to eight hours of sleep a night.

Reduced sleep may decrease energy expenditure(Node #371711)

Tiredness from reduced sleep may curb physical activity during the day(Node #371713)

People who have insufficient sleep are more tired during the day, and as a result may curb their physical activity.

Reduced sleep may increase energy intake(Node #371710)

Reduced sleep gives people more waking time to eat(Node #371712)

Fewer hours of sleep increases the waking time in which people have to eat.

Reduced sleep may increase hunger(Node #371709)

Sleep deprivation may alter the hormones that control hunger (increasing the appetite-stimulating hormone ghrelin and lowering the levels of the satiety-inducing hormone leptin).

Obesogenicity(Node #373989)

The obesogenicity of an environment is the sum of influences that the surroundings, opportunities, or conditions of life have on promoting obesity in individuals or populations’. [1], [2].

Many individuals are consuming more energy than they are expending(Node #352400)

Public Health England estimates that the average man in England is consuming around 300 calories a day more than they would need were they a healthy body weight.

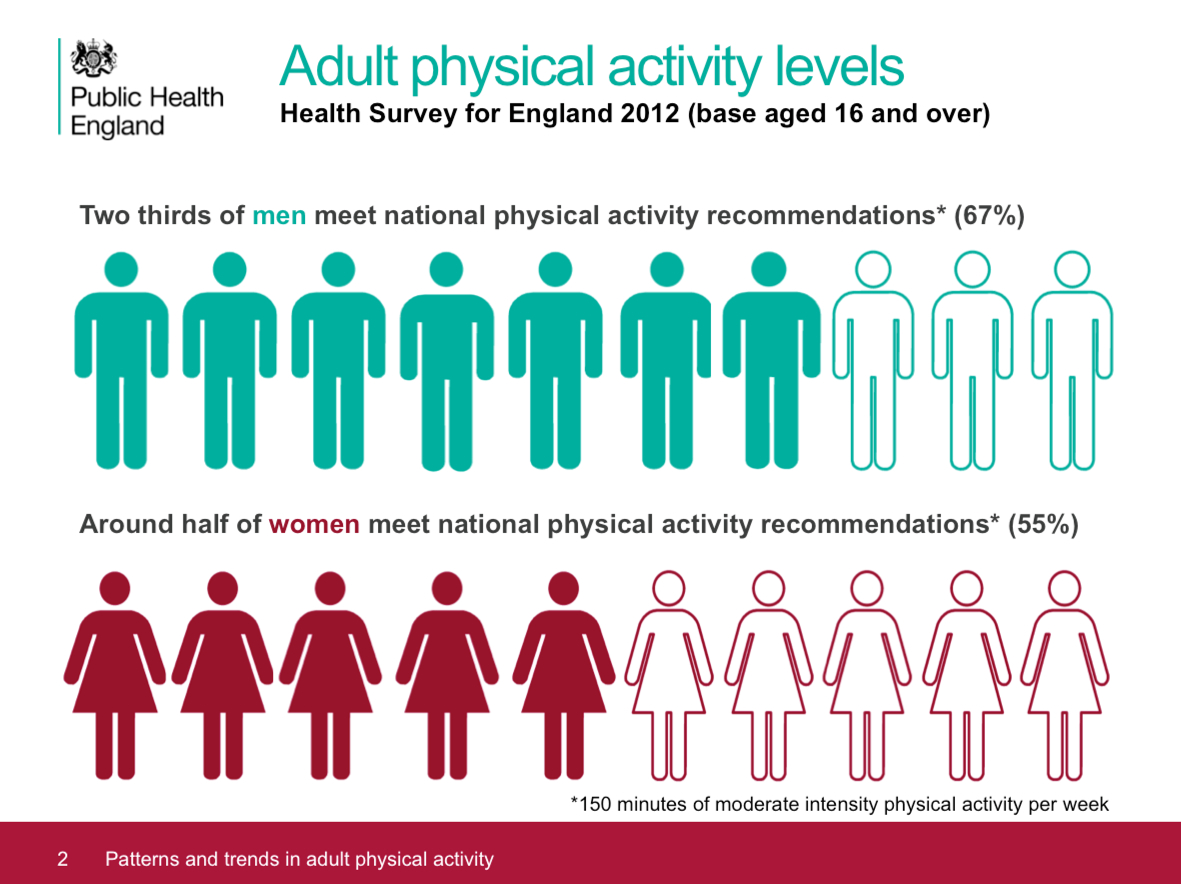

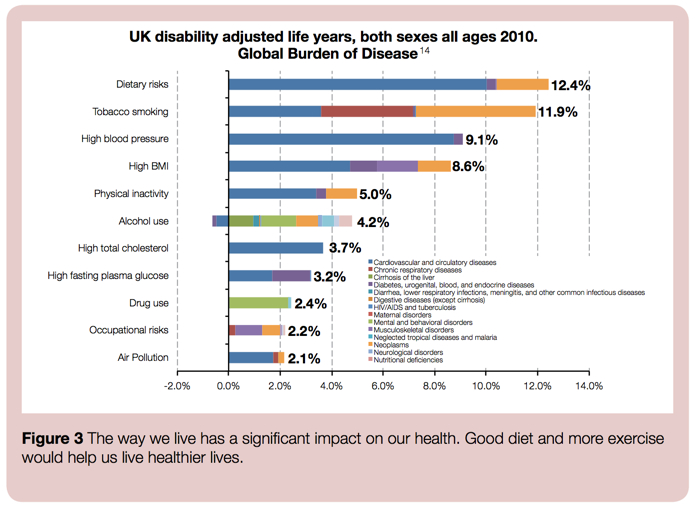

Not building exercise into daily life (Node #352521)A primary cause of the rise in obesity in the UK in recent decades has been a decline in energy expended rather than rise in energy intake; with the changing pattern towards more sedentary lifestyles appearing to be a key factor in this.

Slide: PHE Adult physical activity slide set – July 2015 [6]Around one in two women and a third of men in England are damaging their health through a lack of physical activity. [8]

- over one in four women and one in five men do less than 30 minutes of physical activity a week, so are classified as ‘inactive’. [2]

- physical inactivity is the fourth largest cause of disease and disability in the UK. [7]

Snowdon [1] notes:

If one looks at day-to-day exercise and occupational physical activity, it becomes clear that lifestyles have become more sedentary. The transition from manual labour to office work saw jobs in agriculture decline from eleven to two per cent of employment in the twentieth century while manufacturing jobs declined from 28 to 14 per cent of employment (Lindsay, 2003) [4]. Britons are walking less (from 255 miles per year in 1976 to 179 miles in 2010) and cycling less (from 51 miles per year in 1976 to 42 miles in 2010).

Only 18 per cent of adults report doing any moderate or vigorous physical activity at work while 63 per cent never climb stairs at work and 40 per cent spend no time walking at work (British Heart Foundation, 2012b: 58-59) [3]. Outside of work, 63 per cent report spending less than ten minutes a day walking and 53 per cent do no sports or exercise whatsoever (ibid.: 52-4). Add to this the ubiquity of labour-saving devices and it is clear that Britons today have less need, and fewer opportunities, for physical activity both in the workplace and at home."

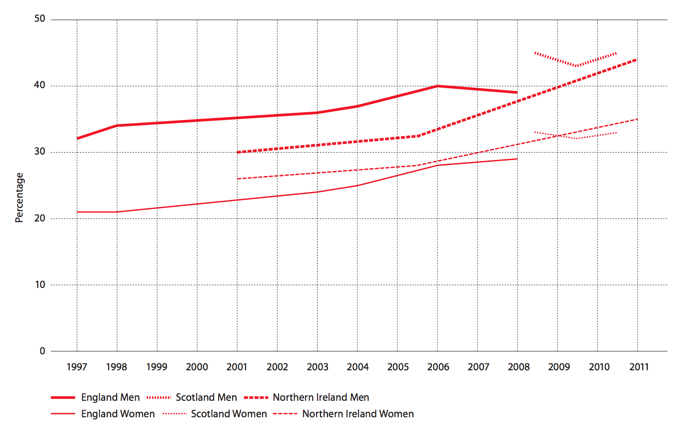

Self-reported physical activity is increasing(Node #371615)The number of people who are self-reporting as meeting the government's recommendation of taking 30 minutes vigorous exercise five times a week rose from 26.5 per cent to 37.5 per cent between 1997 and 2012. [3]

Self-reported percentage of adults meeting the physical activity recommendations, by sex, UK countries 1997 to 2011

Source: British Heart Foundation / University of Oxford [1]

A minority of people are meeting the recommendations(Node #371616)

Although the number of people self-reporting as meeting the government's recommendations is rising, the total number remains a minority of the population.

The recommendations relate only to leisure activities(Node #371617)

The government recommendations, on which people are self-reporting, relate only to leisure activities – and other lifestyle factors (especially the increasingly sedentary patterns of behaviour) may be more significant in this context.

Calorie consumption(Node #352522)

Public Health England estimates that the average man in England is consuming around 300 calories a day more than they would need were they a healthy body weight.

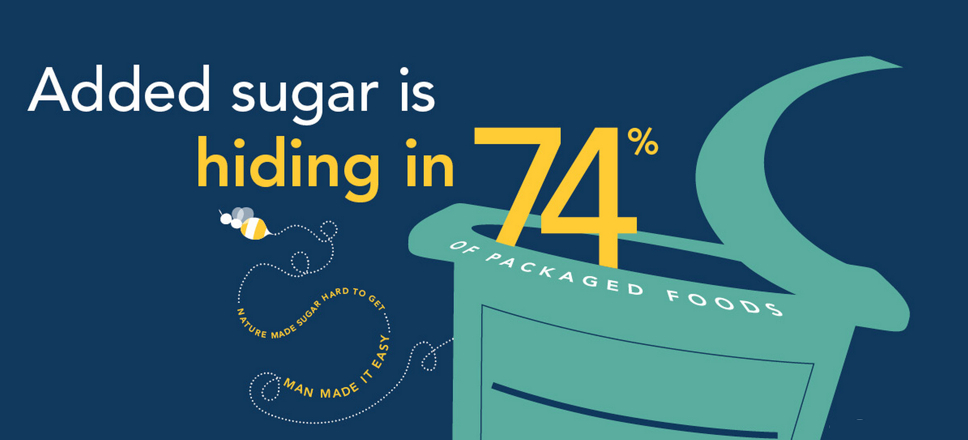

Consuming too much sugar(Node #351718)Many people are eating more sugar than they should. Current intakes of sugar for all population groups exceed recommendations set by the Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy (COMA) for the UK in 1991 (which recommended that, on a population basis, no more than 10% of the average total energy intake should be consumed as sugar). Energy dense diets, such as those that are high in sugar, can lead to an excess calorie intake (which, if sustained, leads to weight gain and obesity).

Consuming more sugar-sweetened beverages(Node #348698) - Drinking just one regular soda a day is the equivalent of consuming over 221,000 sugar cubes over an average lifetime.

- Evidence shows that SSBs are major contributors to childhood obesity [19], [20], as well as to long-term weight-gain, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [21], [22].

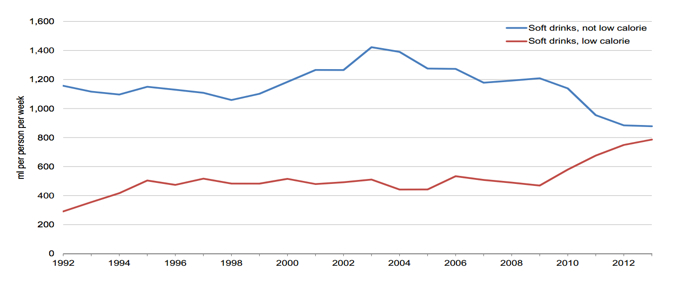

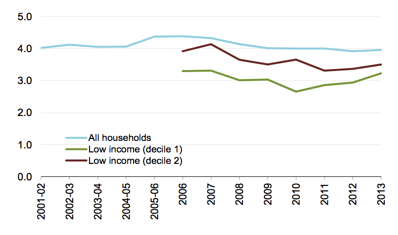

UK purchases of not-low calorie soft drinks are falling(Node #371569)Household purchases of soft drinks were 3.1 per cent lower in 2013 compared to 2010, a fall of 54 grams per person per week. Within this category, household purchases of ‘not low calorie soft drinks’ are on a downward trend since 2010 and fell by 23 per cent between 2010 and 2013 from 1139 to 878 grams per person per week.

UK purchases of soft drink (concentrated and unconcentrated), 1992–2013

Source: DEFRA

- This was mirrored by an upward trend in ‘low calorie soft drinks’ with household purchases 36 per cent higher in the same period up from 579 to 786 grams per person per week.

Sugar(Node #368236)

Definitions of sugar vary. For the purposes of the PHE paper cited, the term ‘sugar’ includes all sugars outside the cellular structure in foods and drinks excluding those naturally present in dairy products. This includes sugar added to foods, plus the sugar in fruit juice and honey. It does not include the sugars naturally present in intact fruit and vegetables or dairy products.

Per capita sugar consumption has fallen by 16% since 1992(Node #371563)

Evidence suggests that per capita consumption of sugar, salt, fat and calories has been falling in Britain for decades. Per capita sugar consumption has fallen by 16 per cent since 1992 and per capita calorie consumption has fallen by 21 per cent since 1974.

WHO recommendations on sugar consumption(Node #400395)The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends (2015) that both adults and children limit their intake of added sugar to less than 10% of total daily calories; with conditional guidance to keep added sugar below 5% of daily calories (i.e. 6 teaspoons – 25 grams – per day for a 2,000-calorie diet).

- WHO recommends a reduced intake of free sugars throughout the lifecourse (strong recommendation).

- In both adults and children, WHO recommends reducing the intake of free sugars to less than 10% of total energy intake (strong recommendation).

- WHO suggests a further reduction of the intake of free sugars to below 5% of

total energy intake (conditional recommendation).

How sugar affects the brain(Node #372888)Eating sugar spikes dopamine levels and leaves a person craving more.

Choosing short-term pleasure over long-term health(Node #352517)

Disconnecting appetite from need and satiety (Node #352515)

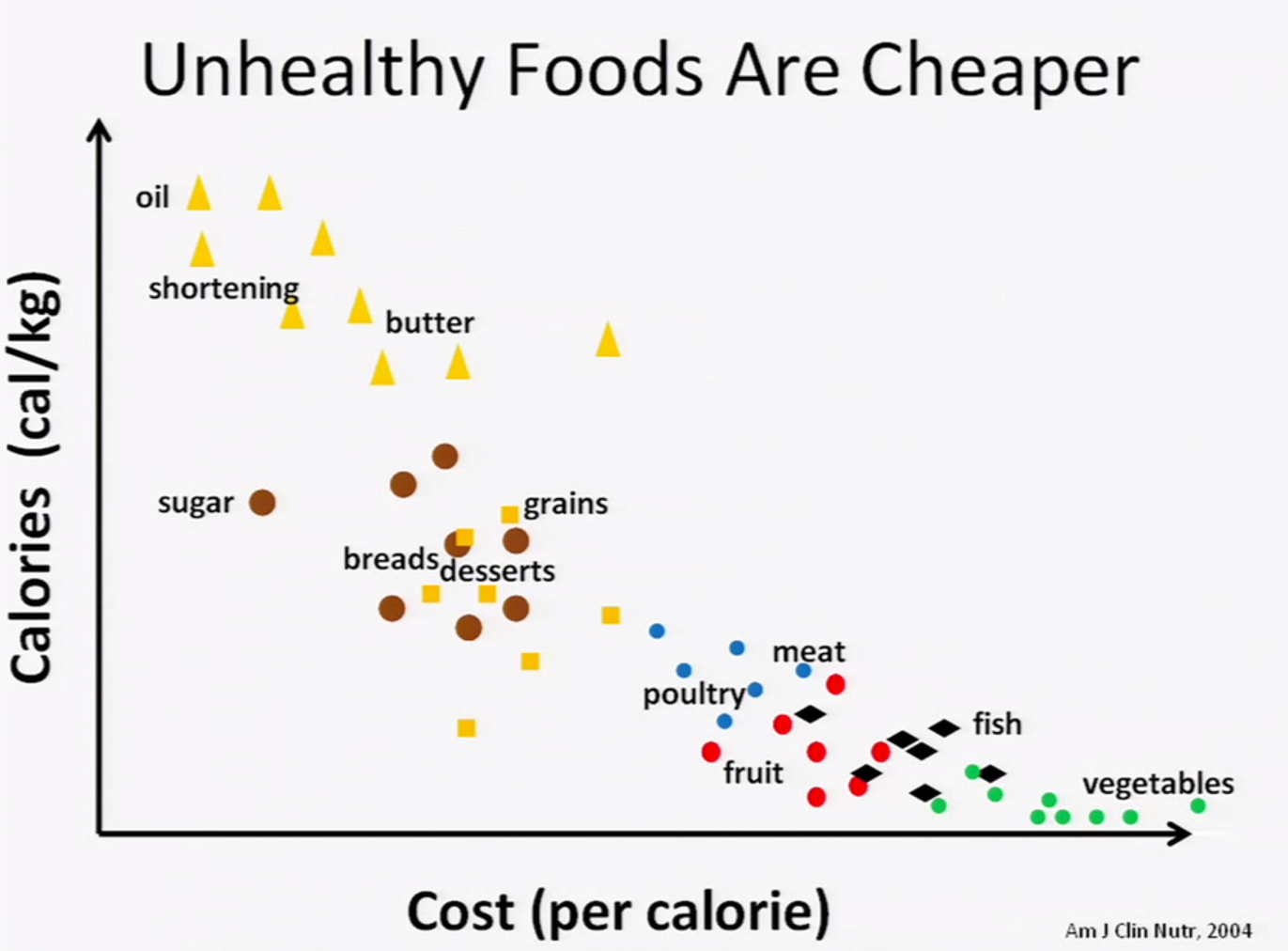

Eating a price-led rather than a nutrition-led diet (Node #352518)

Intake around 5% higher than Estimated Average Requirement for adults(Node #371566)

Total energy intake from all food and drink is around 5 per cent higher than the Estimated Average Requirement for adult intakes.

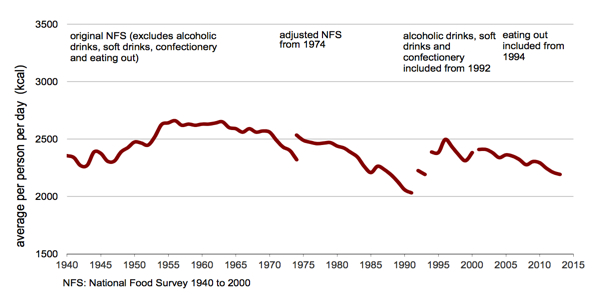

Long term downward trend in total energy intake from all food & drink(Node #371565)Total energy intake per person was an average of 2192 kcal per person per day in 2012, 4.4 per cent lower than in 2010. This is a statistically significant downward trend that confirms the longer term downward trend already apparent since the mid 1960s.

Average energy intake from food and drink since 1940

Source: DEFRA

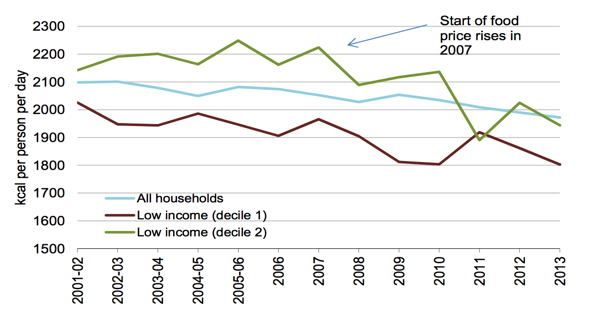

Energy derived from household food and drink 2001-2013

Source: DEFRA

Measuring diet at a societal level is an inexact science(Node #371570)

Measuring diet at a societal level is an inexact science – as researchers generally have to rely on people keeping track of what they eat over a period of several days – and people may be inclined to under report their consumption patterns. Evidence suggests that people may throw away about 10-20% of the food they buy and underreport how much they eat by around 20–40%.

Type of calories consumed is significant (as well the quantity)(Node #371621)

Emerging research suggests that some foods and eating patterns may also make it easier to keep calories in check, while others may make people more likely to overeat. Many of the foods that help prevent disease also seem to help with weight control—foods like whole grains, vegetables, fruits, and nuts. And many of the foods that increase disease risk—chief among them, refined grains and sugary drinks—are also factors in weight gain.

Reluctance to talk about and address implications of own weight(Node #352389)

The weight of the population continues to rise despite media imagery of thin models encouraging a slim ideal that is far out of reach for most of the public. In this context, “Fat” remains an emotive and stigmatic subject – and often perceived as an insult – which makes it harder for people to acknowledge, confront and address their own obesity (and harder for others including health professionals to encourage them to do so too).

Dieting can make lean people fatter(Node #392052)

Dieting to lose weight in people who are in the healthy normal range of body weight is a strong and consistent predictor of future weight gain. [1]

Fat mass / fat-free mass depletion feedback signals are more effective(Node #392175)Lean people regain fat faster because their feedback signals in response to the depletion of both fat mass (i.e. adipostats) and fat-free mass (i.e. proteinstats) – through the modulation of energy intake and adaptive thermogenesis – are more effective than in individuals with overweight or obesity, thus resulting in a faster rate of fat recovery relative to recovery of lean tissue (i.e. preferential catch-up fat) [1], [2]

"In fact, it appears that lean people overshoot in terms of weight gain because the state of hyperphagia (in response to weight loss) appears to persist well beyond complete recovery of fat mass and interestingly until fat free mass is fully recovered (which may take months during which time fat gain continues)." [1]

Obesity alters neurocircuitry to increase susceptibility to overeating(Node #371333)

Obese people have alterations in dopamine neurocircuitry that may increase their susceptibility to opportunistic overeating while at the same time making food intake less rewarding, less goal directed and more habitual. Whether or not the observed neurocircuitry alterations pre-existed or occurred as a result of obesity development, they may perpetuate obesity given the omnipresence of palatable foods and their associated cues.

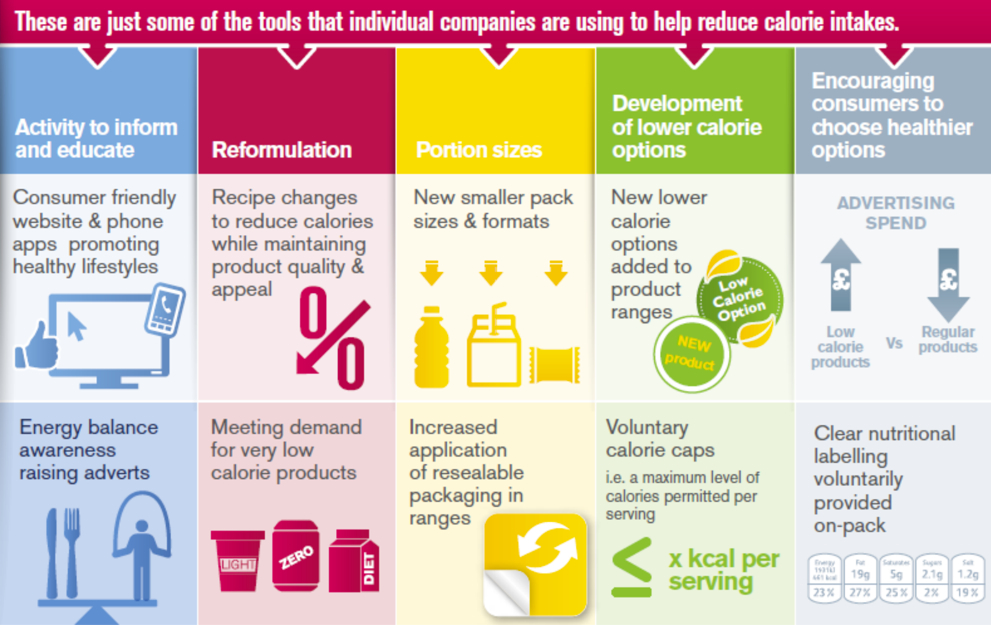

Strategies of some companies are fuelling the obesity crisis(Node #351042)

Some companies and industries are fuelling the obesity crisis, through a variety of strategies that prioritise profitability and corporate brand value over public health, and, in the process, externalise significant costs.

Production and marketing choices favour profit over diet optimisation(Node #368179)

Decisions made by many food and beverage companies tend to be shaped more by the immediate corporate financial interests of shareholders (and the associated interests of corporate officers) rather than the social goal of achieving optimal human diets; as reflected in, for example, the production and marketing a high volume of low-cost, highly processed foods that are rich in sugar, salt, and saturated fats.

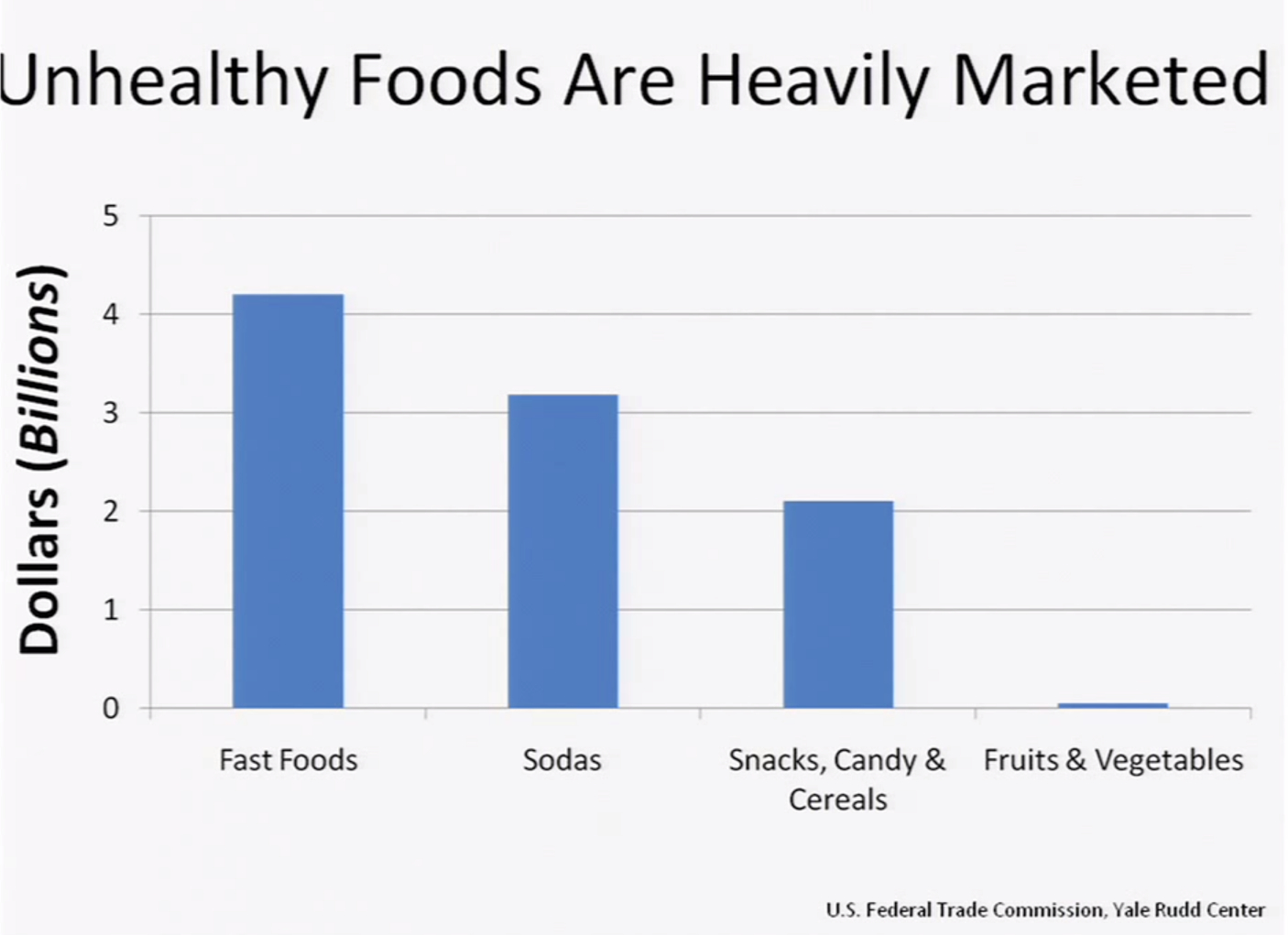

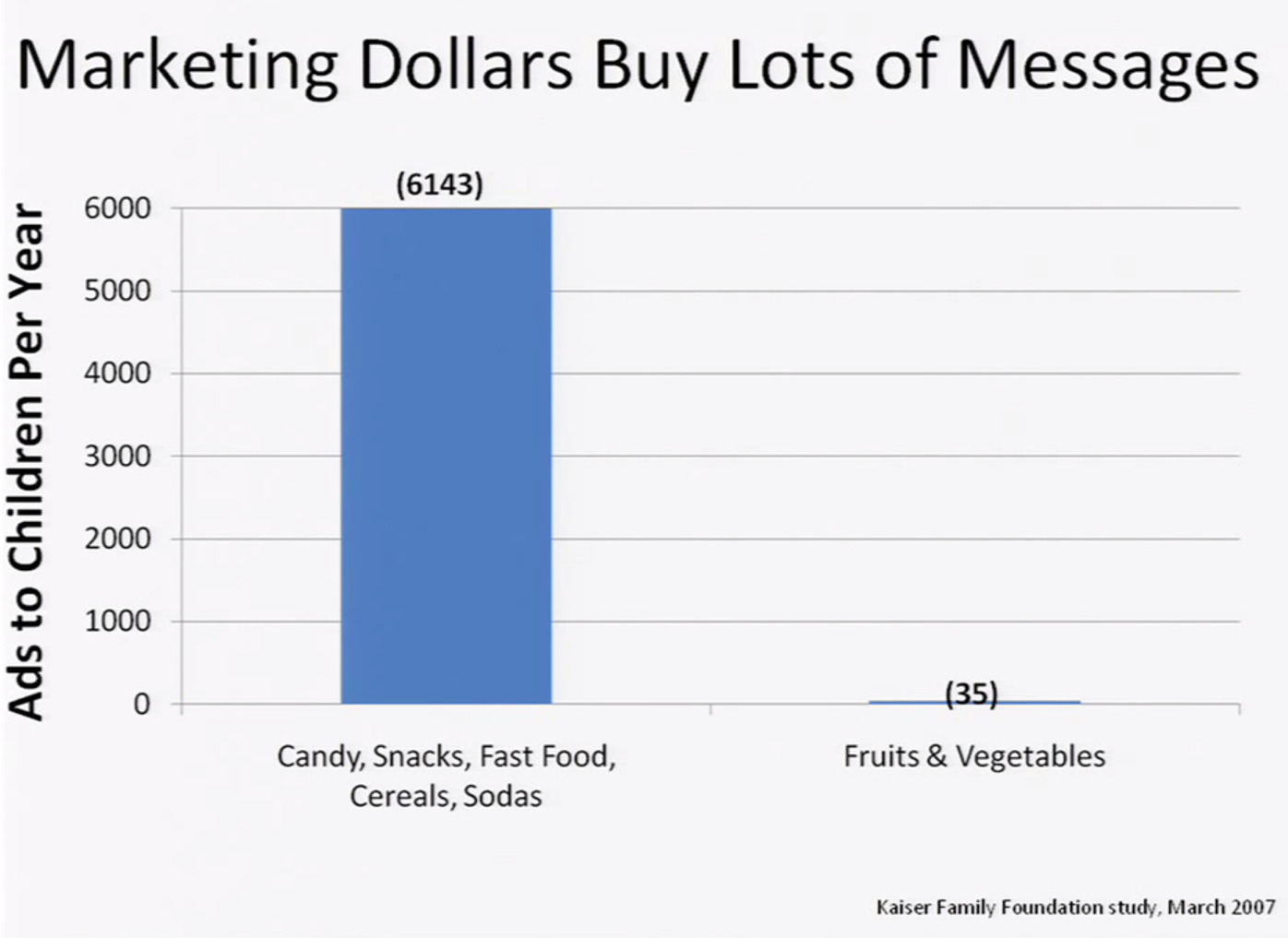

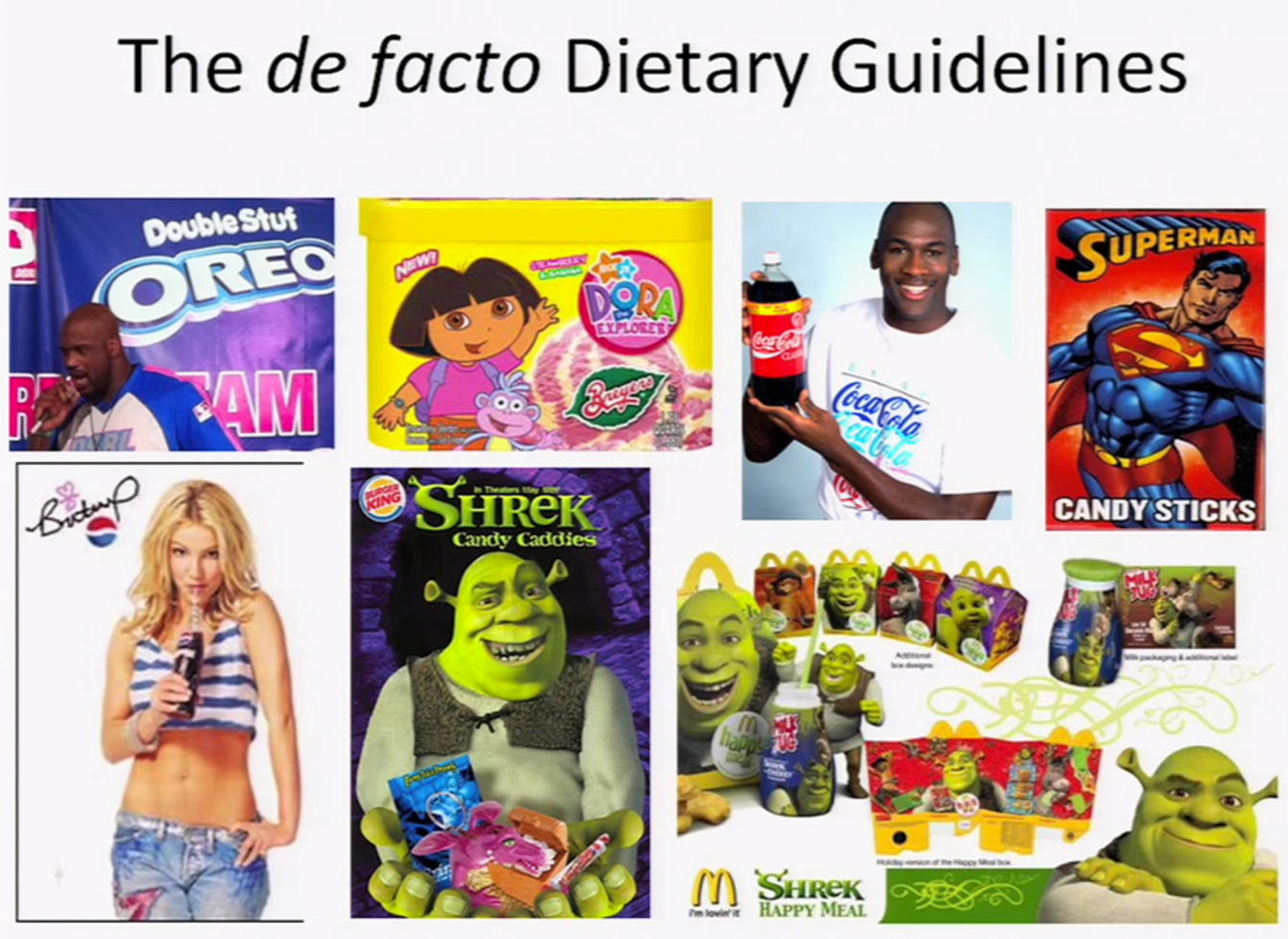

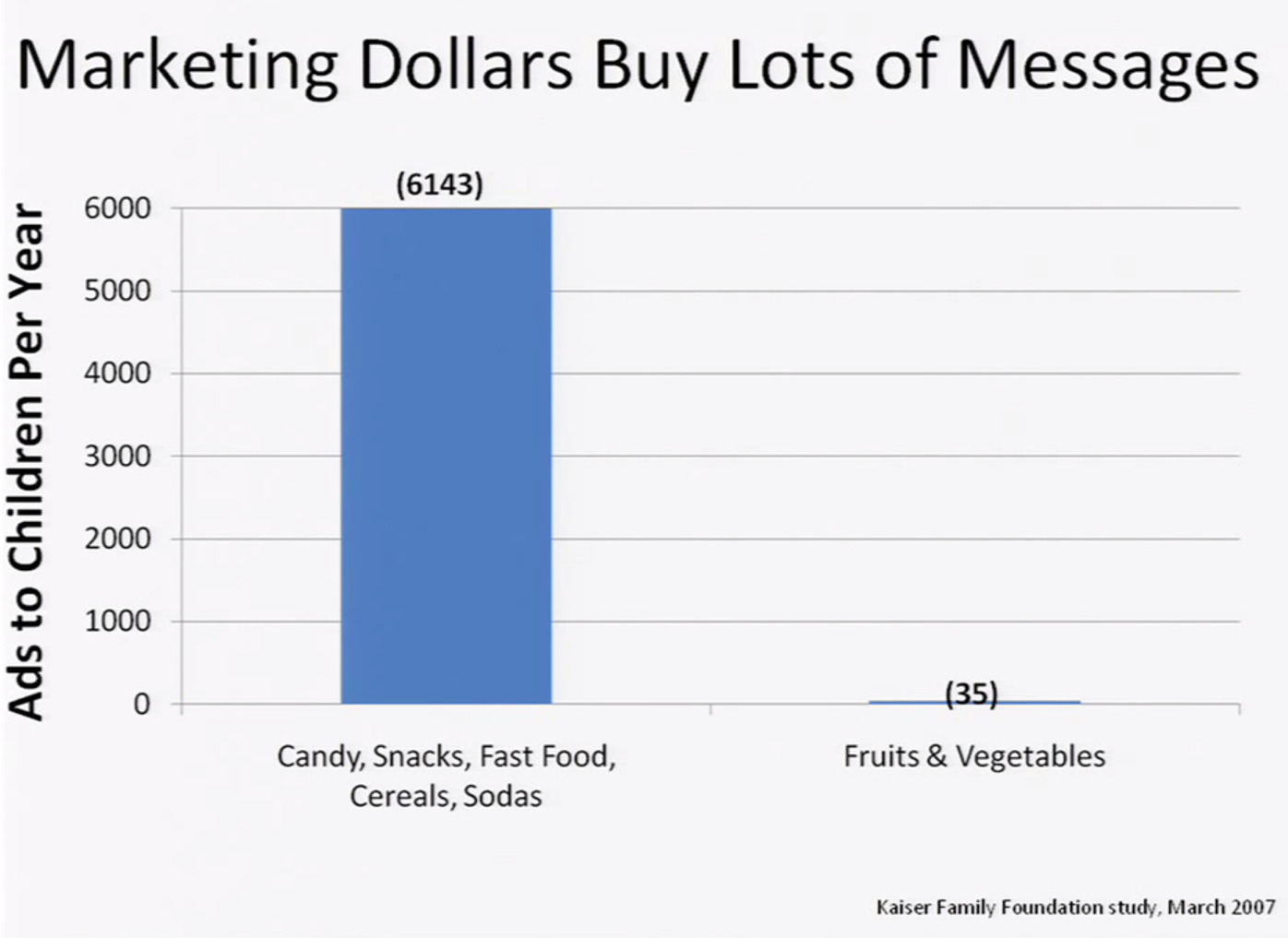

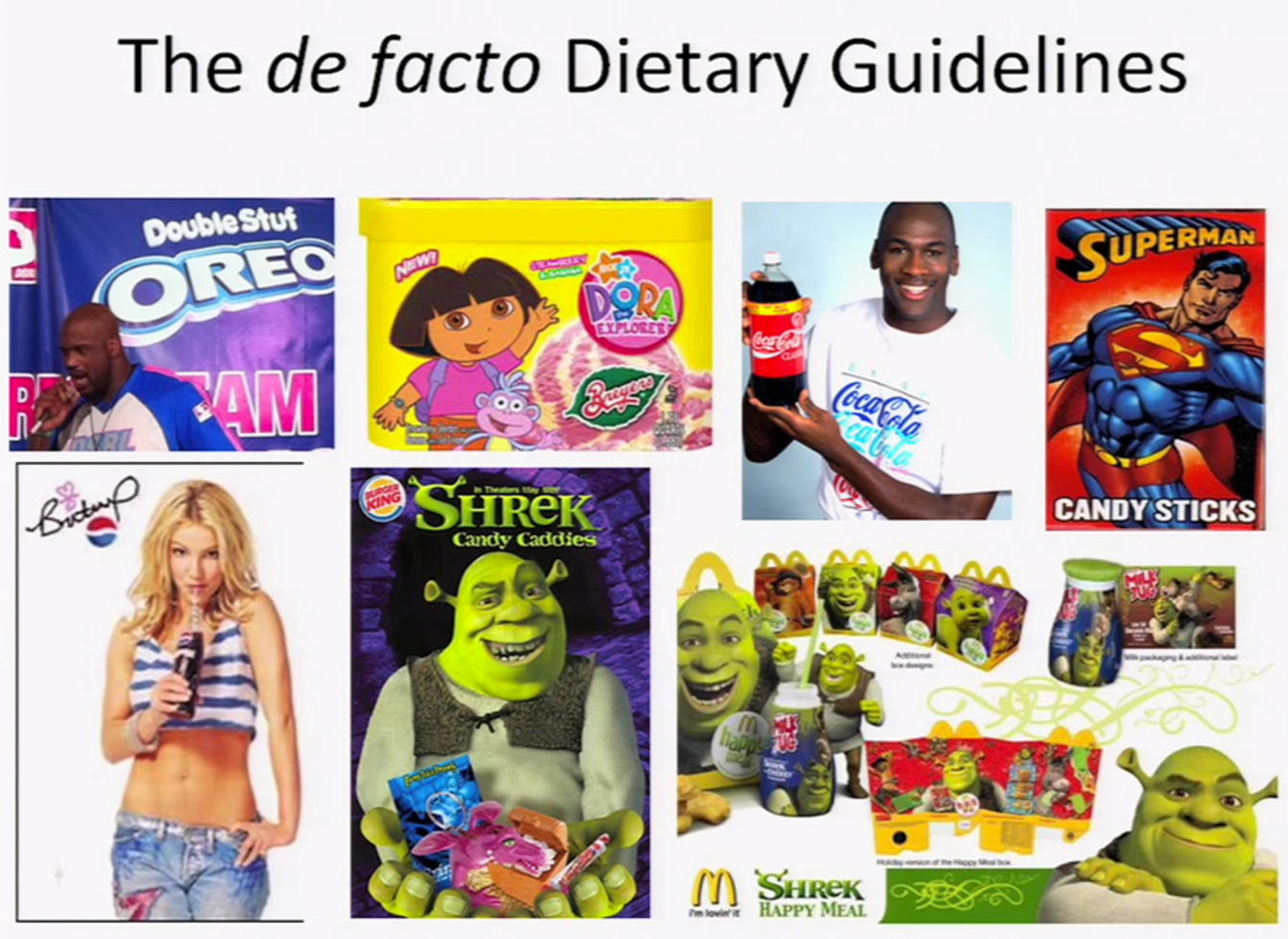

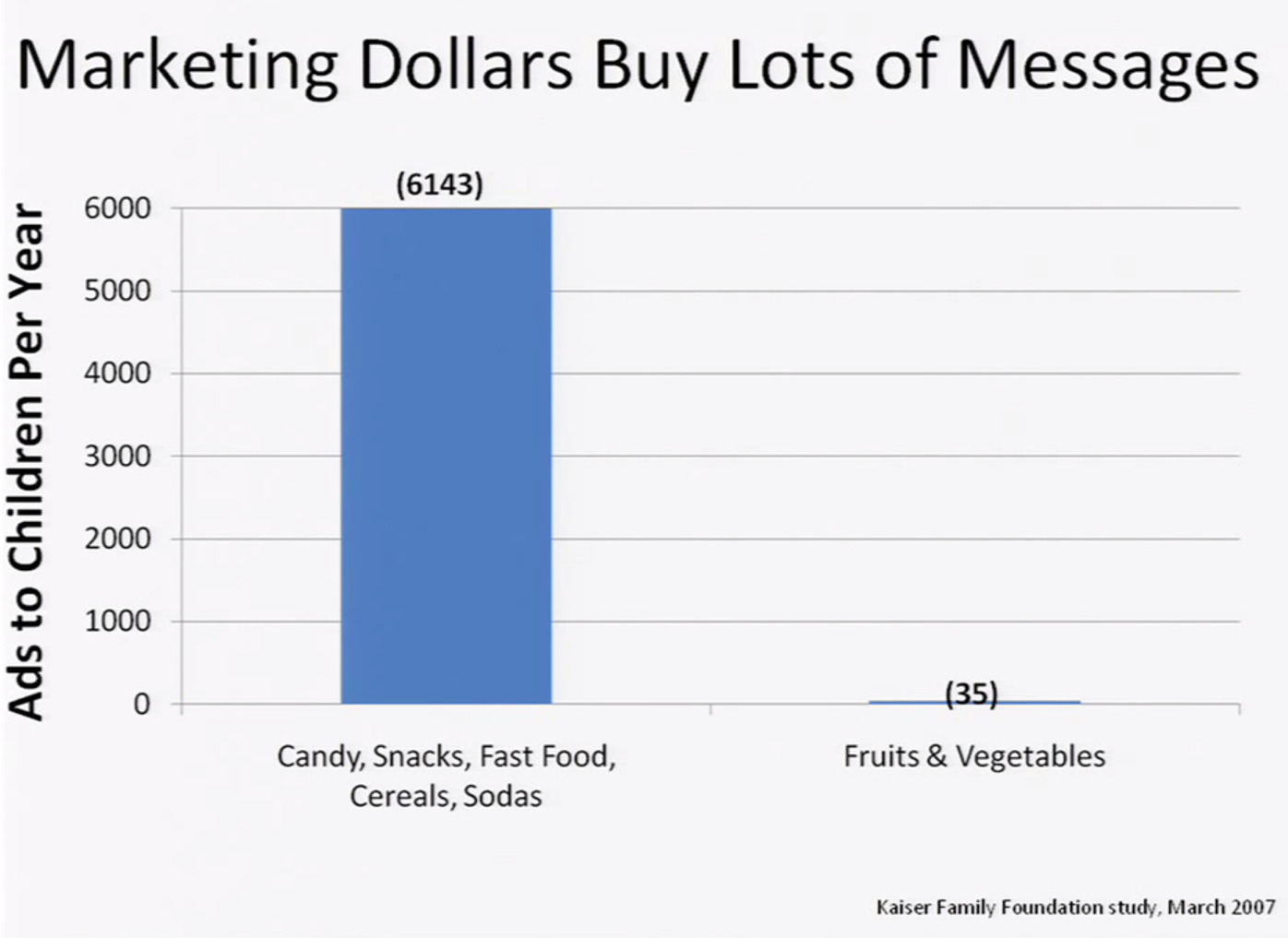

Advertising and marketing reinforce new eating patterns (Node #352388)Marketing and advertising instil and reinforce new cultural norms about what (e.g. fast food) and how to eat (e.g. snacking), and how much (e.g. larger portions) to eat.

Sources: Scott Kahan, U.S. Federal Trade Commission, Yale Rudd Center, Kaiser Family Foundation

Targeting advertising at children(Node #368175)Advertising and other marketing approaches are targeted at children and other vulnerable groups.

Sources: Scott Kahan, Kaiser Family Foundation

Impact of swapping away from sugary cereals(Node #371332)Swapping to plain cereals can cut your family's sugar intake by a quarter of a 1kg bag of sugar over 4-weeks.

Portions have grown larger(Node #370364)

Source: Scott Kahan

Ready-to-eat food is more readily available(Node #370366)

Ready-to-eat food is increasingly available in industrial societies 24-hours a day and in places where food wasn't traditionally available (such as pharmacies and petrol stations), as well as via the growing number of fast food restaurants and coffee shops.

Fast food outlets – England(Node #371775)The concentration of fast food outlets and takeaways varies by local authority in England. The scatter plot shows a strong association between deprivation and the density of fast food outlets, with more deprived areas having more fast food outlets per 100,000 population. [1]

Growth in restaurants and dining out(Node #371727)The restaurant industry has almost doubled its share of every dollar spent on food in the United States over the last 60 years from 25% in 1955 to 47% today. Much of this growth reflects the expansion in fast food restaurants (a trend observed in other countries including the UK).

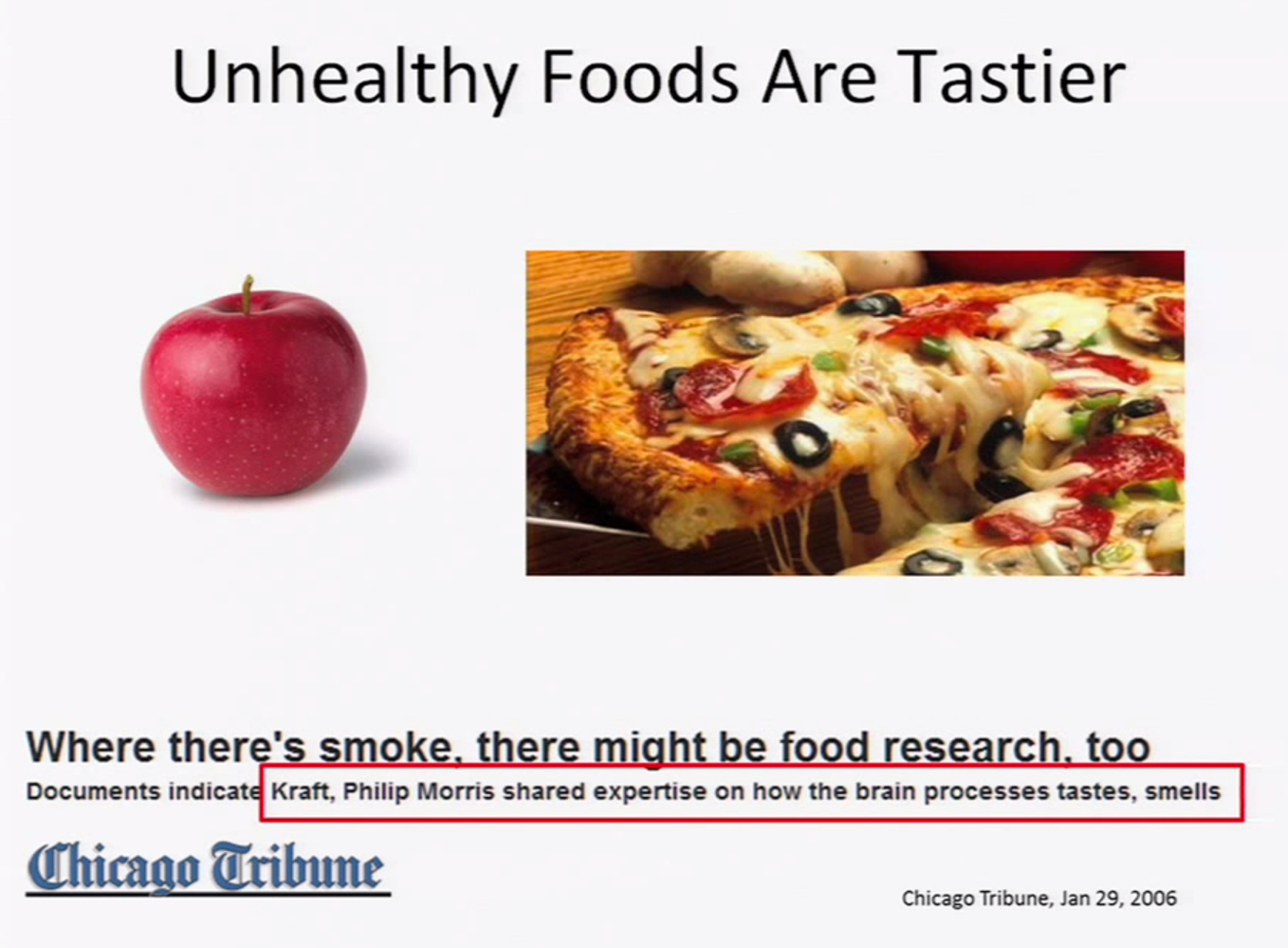

Unhealthier foods are engineered to be tastier(Node #370365)Food scientists have become adept at understanding how our brains respond to, and react to, and crave tastes, smells and textures, and have become adept at engineering and processing foods to take advantage of that – largely by adding lots of salt, sugar and fat – and to make these foods almost irresistible to our brains.

Sources: Scott Kahan, Chicago Tribune (2006)

- Although in theory minimal processing of foods can improve nutritional content, in practice most processing is done so to increase palatability, shelf-life, and transportability (and these processes tend to reduce nutritional quality). [2]

The addictiveness of sugar(Node #351120)Some companies are harnessing the addictiveness of sugar for commercial benefit and to the detriment of public health. Emerging science on the addictiveness and toxicity of sugar, especially when combined with the known addictive properties of caffeine found in many sugary beverages, points to a large-scale public health threat similar to addictiveness and harmful impacts of tobacco products.

Robert H. Lustig, MD, UCSF Professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Endocrinology, explores the damage caused by sugary foods. He argues that fructose (too much) and fiber (not enough) appear to be cornerstones of the obesity epidemic through their effects on insulin. Series: UCSF Mini Medical School for the Public [7/2009]

Fructose doesn't stimulate insulin or leptin or suppress ghrelin(Node #351139)

Fructose changes the way that the brain recognizes energy, so that the brain doesn't suppress appetite.

Fructose is 7 times more likely than glucose to form AGE's(Node #351137)

Fructose is 7 times more likely than glucose to form Advanced Glycation End-Products.

Fructose raises tryglicerides – a high sugar diet is a high fat diet(Node #351144)

Although fructose is a carbohydrate it is metabolized like a fat – a corollary of this is that a low fat diet isn't really low fat, because the fructose/sucrose doubles as fat.

HFCS products are sweeter and cheaper than cane sugar products(Node #366446)

Products with High Fructose Corn Syrup are sweeter and cheaper than products made with cane sugar.

Fructose is sweeter than glucose(Node #366444)

High fructose corn syrup is cheaper than cane sugar(Node #366445)

High fructose corn syrup is cheaper than sugar due to government farm bill corn subsidies in the US.

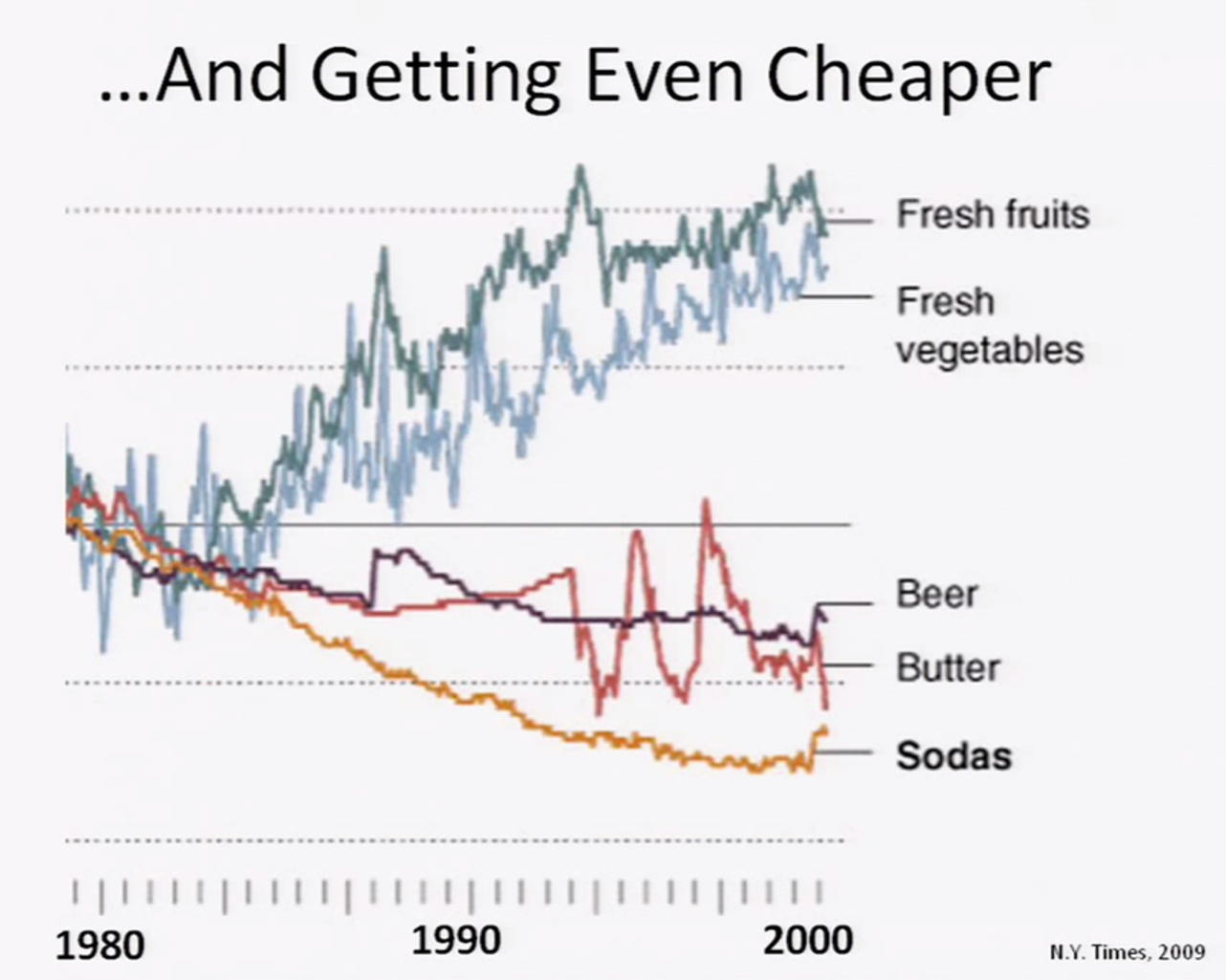

Unhealthy foods are cheaper and getting cheaper(Node #370363)

Sources: Scott Kahan, Am J Clin Nutr (2004), New York Times (2009)

Public health interventions are often resisted(Node #351043)Evidence suggests that, for example, some food and beverage companies are adopting similar tactics to those adopted earlier by the tobacco companies to avoid public health interventions (such as taxation and regulation) that might threaten their profits.

From Moodie et al. [6]:

- Transnational corporations are major drivers of non-communicable disease epidemics and profit from increased consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink (so-called unhealthy commodities).

- Alcohol and ultra-processed food and drink industries use similar strategies to the tobacco industry to undermine effective public health policies and programmes.

- Unhealthy commodity industries should have no role in the formation of national or international policy for non-communicable disease policy.

- Despite the common reliance on industry self-regulation and public–private partnerships to improve public health, there is no evidence to support their effectiveness or safety.

- In view of the present and predicted scale of non-communicable disease epidemics, the only evidence-based mechanisms that can prevent harm caused by unhealthy commodity industries are public regulation and market intervention

Adopting lessons from the Tobacco Playbook(Node #351113)The tobacco industry had a playbook, a script, that emphasized personal responsibility, paying scientists who delivered research that instilled doubt, criticizing the “junk” science that found harms associated with smoking, making self-regulatory pledges, lobbying with massive resources to stifle government action, introducing “safer” products, and simultaneously manipulating and denying both the addictive nature of their products and their marketing to children.

From Dorfman et al:

"Tobacco companies launched CSR campaigns to rehabilitate themselves with the public when their image had been tarnished [20]. Because the most comprehensive initiatives were introduced well after intense public outcry, however, their CSR efforts struggled to achieve their aims [42]. As soda denormalization is nascent, soda companies may enjoy benefits from CSR that Big Tobacco labored to accomplish. In addition to effectively preempting regulation and maintaining its favorable position with the public, the soda industry's CSR tactics may also entice today's young people to become brand-loyal lifetime consumers, an outcome that current social norms dictate Big Tobacco cannot explicitly seek.

Without sustained denormalization of soda, it will be harder for public health advocates to see why partnering with industry may further the companies' goals more than their own. While tobacco denormalization was facilitated by litigation, which used the discovery process to procure internal documents revealing the industry's duplicitous intent, it is possible to respond to the soda industry without a “smoking gun.”

For example, one instance of tobacco industry denormalization that did not rely on internal documents was the revelation that PM spent more on publicizing its charitable efforts than it spent on the charities itself, which exposed the cynical nature of Big Tobacco's CSR [114]. The Refresh Project's $20 million price tag, and the statements from company representatives, give public health advocates a similar opportunity to argue that this is marketing, not philanthropy [115].

Such criticism appeared in a Lancet editorial, which stated that the U.K.'s Change4Life should have avoided “ill-judged partnerships with companies that fuel obesity” [116]. Research on the health harms of sugary beverages can help advocates name these products as one of the “biggest culprits” [117] behind the obesity crisis.

Emerging science on the addictiveness [118] and toxicity [119] of sugar, especially when combined with the known addictive properties of caffeine found in many sugary beverages, should further heighten awareness of the product's public health threat similar to the understanding about the addictiveness of tobacco products.

Public health advocates must continue to monitor the CSR activities of soda companies, and remind the public and policymakers that, similar to Big Tobacco, soda industry CSR aims to position the companies, and their products, as socially acceptable rather than contributing to a social ill."

Shaping public understanding and scientific research(Node #371078)Well-resourced food companies are able to recruit leading nutritional scientist, experts and researchers to guide and justify product development, reformulation and health impact. Research suggests that studies funded by industry are 4- to 8-fold more likely to support conclusions favourable to the industry.

Successive governments have made counterproductive policy choices(Node #352399)

The growing prevalence of obesity in the UK is partly the result of well-intentioned but counterproductive policy choices made by successive governments over several decades.

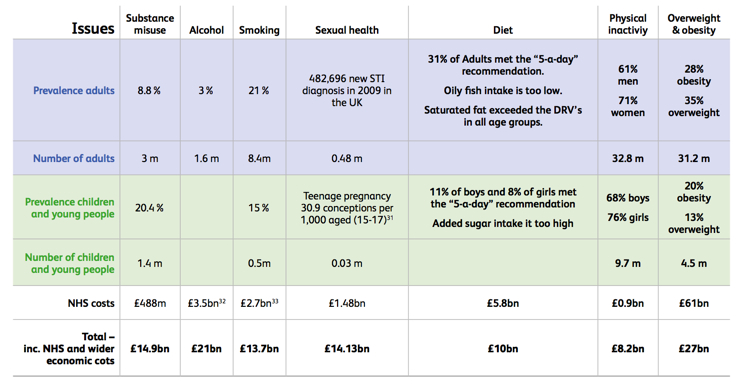

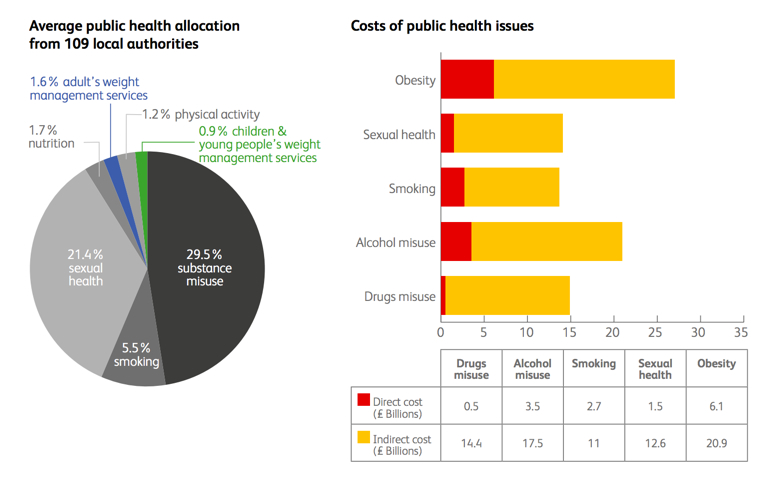

Giving obesity a disproportionately low public health priority(Node #352558)The table below (via HOOP) [1] provides a summary of each of the public health issues, the prevalence of the issue in adults and children and young people as well as the direct NHS and indirect social and economic costs, (where data is available):

View full size>>

- Despite the higher direct and indirect costs, the allocation of public health funds by local authorities to help overweight and obese people to lose weight is significantly lower than the allocation for other public health issues.

- This is short sighted and this lack of action is the primary reason we are not seeing progress on tackling obesity.

- Why central government funding for weight management services is not available whilst £2bn worth of central government funding has been made available for substance misuse (in addition to already high local authority investment).

- Evidence seems to suggest that both central and local governments are either not aware of the disparity or they are simply not taking the issue of obesity seriously when compared to other public health issues.

- Given evidence that weight management services are cost effective local and central governments should be prioritising investments that provide a positive return.

View full size>>

Inconsistent prioritisation of measures to protect population health(Node #352525)

Government patterns of interventions to protect the health of the population are inconsistent (e.g. interventions on smoking but not nutrition).

Paucity of investment in intervention measures(Node #366463)

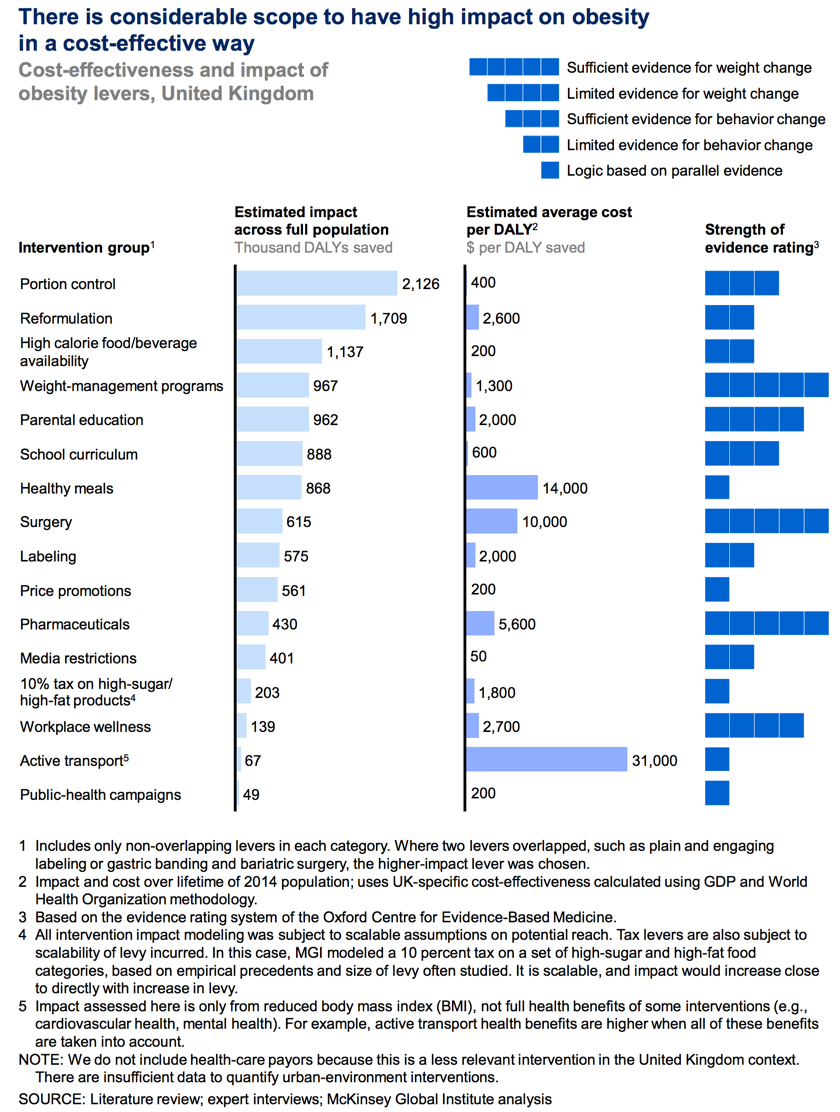

The UK invests less than $1 billion a year in prevention activities such as weight-management programs and public health campaigns – i.e. around 1% of the social cost of obesity in the UK. More investment is required.

Weight management services in the UK are poorly developed(Node #352559)Although the prevalence of obesity in adults and in children in the UK is amongst the highest in the developed world, the multidisciplinary services necessary to manage patients with an established problem of excess weight and its clinical consequences are poorly developed within the UK. Some prevention and intervention strategies are provided in primary care, but secondary care and specialist services remain underdeveloped or unavailable to meet the need.

- Some prevention and intervention strategies are provided in primary care, but secondary care and specialist services remain underdeveloped or unavailable to meet the need.

Overseeing a decline in physical activity(Node #352531)

Successive governments have overseen a decline of physical activity (e.g. due to policies on transport, public spaces, and sports facilities).

Prioritising car use in retail and transport planning(Node #352532)

Subsidising the production of sugar and fat(Node #352528)

Governments are subsidising production of fat and sugar compared with micronutrient-rich foods.

EU Common Agricultural Policy(Node #370190)

The burden of diet-related disease has grown considerably since the introduction of the common agricultural policy (CAP) – the overarching framework used by EU member countries to form their own agricultural policies – which has subsidised the production of dairy products, red meat and sugar, and resulted in the systematic destruction of large quantities of fruit and vegetables.

Allowing an asymmetry of information on food, nutrition and health(Node #352527)Health education is overwhelmed by other marketing messages – generating an asymmetry of information flow and education on nutrition and health.

Sources: Scott Kahan, Kaiser Family Foundation

WHO's total budget is less than half the marketing budget of McDonalds(Node #366896)

McDonald’s and Coca-Cola’s marketing budgets are each twice the World Health Organization’s full-year budget.

Insufficient countervailing checks to oligopoly in food supply chains(Node #351336)The majority of what most people eat is driven increasingly by the production and distribution decisions of a few multinational food companies, whose oligopolistic interest are not necessarily aligned with the public health interest. Successive governments have failed to establish sufficient countervailing public policy measures to ensure that, where these interests are not aligned, the oligopolistic interests of the companies don't impact negatively on public health.

Background on the oligopoly in the global food system: [2]

- In the United States, the ten largest food companies control over half of all food sales [4] and worldwide this proportion is about 15% and rising.

- More than half of global soft drinks are produced by large multinational companies, mainly Coca-Cola and PepsiCo. [5] Three-fourths of world food sales involve processed foods, for which the largest manufacturers hold over a third of the global market.

- Big Food is a driving force behind the global rise in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) and processed foods enriched in salt, sugar, and fat. [5]

Companies also deliver significant benefits(Node #368200)

Companies are source of food technology innovation(Node #368195)

Food companies are large employers(Node #368177)

Food companies are significant benefactors to political parties(Node #368178)

Food companies reduce the risk of undernutrition(Node #368194)

Advice to shift to low-fat diets may have been counterproductive(Node #371618)

Encouragement over the last 30 years to shift towards low-fat diets as the key to healthy weight and good health may have been misguided—as evidence suggests that low-fat diets don't make it easier to lose weight and don't appear to offer any special health benefits—and counterproductive as low-fat diets are often high in carbohydrates (especially from rapidly digested sources, such as white bread and white rice) which increase the risk of weight gain, diabetes, and heart disease.

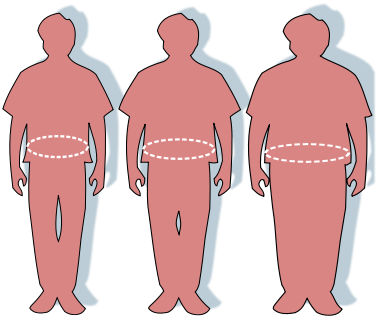

What is obesity?(Node #352454)Obesity is a medical condition in which excess body fat has accumulated to the extent that it may result in increased health problems and reduced life expectancy. As central obesity (excess ectopic fat stored around major organs and abdomen) is the most dangerous form to health, waist measurement can be a key indicator of risk. Generally, men with a waist circumference of 94cm or more (and women of 80cm or more) are more likely to develop obesity-related health problems.

Illustration of obesity and waist circumference From left to right, as labeled in the original image, the "healthy" man has a 33 inch (84 cm) waist, the "overweight" man a 45 inch (114 cm) waist, and the "obese" man a 60 inch (152cm) waist. (image source) (image reference) Source: Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2000. Infographic: FDA/Renée Gordon / Wikipedia

Body Mass Index (BMI) is also used as an indicator of healthy weight for height (although people who are very muscular can have a high BMI, without excess fat). For most adults:

- a BMI of 25 to 29.9 is considered overweight;

- a BMI of 30 to 39.9 is considered obese; and,

- a BMI of 40 or above is considered severely obese.

Older patients, in particular, may have a normal BMI while having a waist measurement which places them into the high risk category.

The Royal College of Physicians [4] notes that:

- Obesity is strongly heritable (60% of weight variance is attributed to heredity) yet currently known gene mutations and polymorphisms account for <5% of weight variability.

- Diagnosis by BMI requires measuring height and weight accurately; risk stratification in overweight and modest obesity requires measuring waist circumference and possibly the use of a clinical staging system (Edmonton Obesity Staging System (EOSS)).

- Prevention and long-term weight loss maintenance require sustained changes in diet and physical activity habits.

- Obesity is a major risk factor in diabetes (5 x), cancer (3 x the risk of colon cancer), and heart disease (2.5 x).

- Modest weight loss (~10 kg) helps to improve diabetes, improves quality of life and reduces morbidity.

- An energy deficit of only 100 calories per day predicts a 0.5 kg weight loss in a month.

- Cost-effective treatments in appropriate patients include weight loss programmes (commercial: e.g. WeightWatchers; GP delivered: eg Counterweight); pharmacotherapy (egorlistat); and bariatric surgery.

Assessing health risk and intervention(Node #370012)The latest guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence on the assessment of the health risk arising from obesity and associated interventions.

| BMI classification | Waist circumference |

| Low | High | Very high |

| Overweight | No increased risk | Increased risk | High risk |

| Obesity I | Increased risk | High risk | Very high risk |

- For men, waist circumference of less than 94 cm is low, 94–102 cm is high and more than 102 cm is very high.

- For women, waist circumference of less than 80 cm is low, 80–88 cm is high and more than 88 cm is very high.

| BMI classification | Waist circumference | Comorbidities present |

| Low | High | Very high |

| Overweight | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Obesity I | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Obesity II | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Obesity III | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

1 = General advice on healthy weight and lifestyle

2 = Diet and physical activity

3 = Diet and physical activity; consider drugs

4 = Diet and physical activity; consider drugs; consider surgery

Shortcomings of BMI?(Node #371489)

Although BMI is used widely as an indicator of obesity it has several shortcomings as an indicator.

Limited diagnostic accuracy(Node #371490)

The diagnostic accuracy of BMI to diagnose obesity is limited, particularly for individuals in the intermediate BMI ranges.

The BMI-mortality curve isn't constant for age(Node #371491)

BMI should be interpreted differently for different age groups.

The Obesity Paradox: higher BMI may not always be bad(Node #371492)

Research suggests that while being underweight and highly obese are both associated with increased mortality relative to the normal weight category, being overweight is not associated with excess mortality. Moreover, people with obesity who have preserved fitness and have no notable metabolic abnormalities have a very favourable prognosis; suggesting that improving fitness rather than weight loss per se should be emphasised in patients with overweight and class I obesity (BMI 30–35 kg/m2).

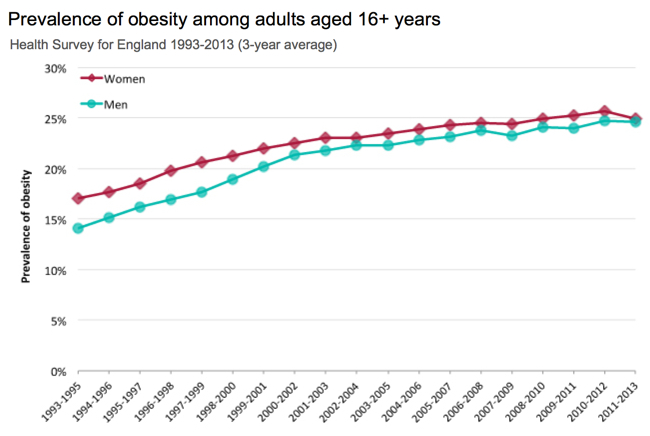

Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet – England 2014(Node #371564)Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet in England from the Health & Social Care Information Centre.

Obesity

- The proportion of adults with a normal Body Mass Index (BMI) decreased between 1993 and 2012 from 41.0% to 32.1% among men and from 49.5% to 40.6% among women.

- There was a marked increase in the proportion of adults that were obese between 1993 and 2012 from 13.2% to 24.4% among men and from 16.4% to 25.1% among women.

- The proportion of adults that were overweight including obese increased between 1993 and 2012 from 57.6% to 66.6% among men and from 48.6% to 57.2% among women.

- The proportion of adults with a raised waist circumference increased from 20% to 34% among men and from 26% to 45% among women between 1993 and 2012.

- In Reception class in 2012/13, the proportion of obese children (9.3%) was lower than in 2011/12 (9.5%) and also lower than in 2006/07 (9.9%) (when data was first published).

- In Year 6 in 2012/13, the proportion of obese children (18.9%) was lower than in 2011/12 (19.2%) but higher than in 2006/07 (17.5%).

Physical activity In 2012

- 67% of men and 55% of women aged 16 and over met the new recommendations for aerobic activity. 26% of women and 19% of men were classed as inactive.

- 46% of men and 37% of women reported walking of at least moderate intensity for 10 minutes or more on at least one day in the last four weeks.

- 52% of men and 45% of women had taken part in sports/exercise at least once during the past four weeks.

Diet

- While overall purchases of fruit and vegetables reduced between 2009 and 2012, consumers spent 8.3% more on fresh and processed vegetables and 11.7% more on fresh and processed fruit.

- Total expenditure on household food and non-alcoholic drink rose by 4.3% in 2012 from the previous year and was 8.9% higher than in 2009. There have been significant upward trends in household expenditure on total fats and oils, butter, sugar and preserves, fruit and fruit juice, soft drinks and beverages.

Impacts of obesity(Node #348688)Obesity presents a significant threat to the health of the UK population and a significant drain on the nation's financial resources. 24.9% of adults in England are obese—with a body mass index of over 30—62% of adults are either overweight or obese (with a BMI of over 25), and 32% of 10–11-year-olds are overweight or obese. The annual cost of obesity to the UK is estimated to be £27bn–£46bn [1], [2]; although international comparisons suggest that the true cost could be significantly higher.

Source: Public Health England – Obesity

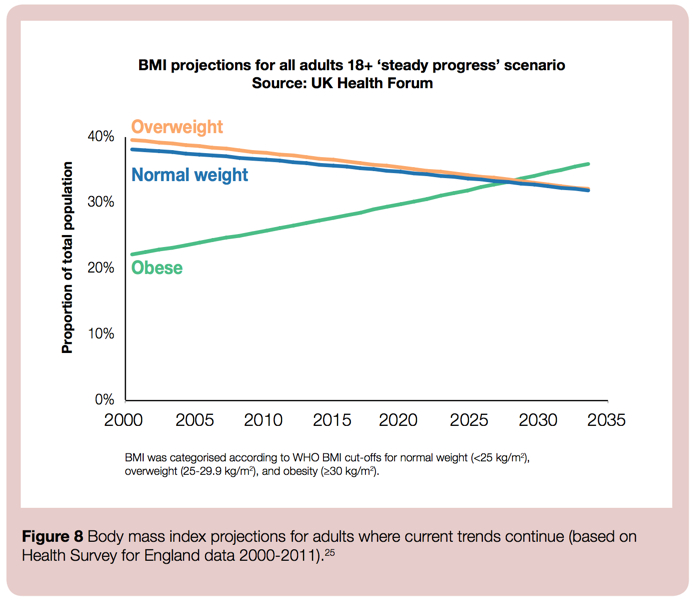

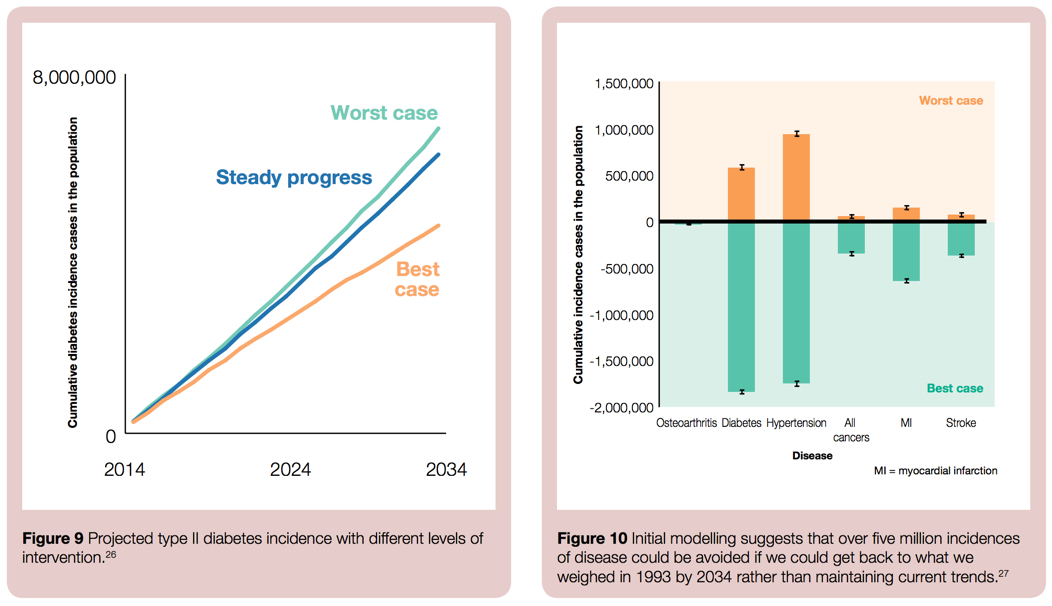

If the historic trends persist, one in three people will be obese by 2034 [6] (see chart below); although there are encouraging signs that the trend appears to have levelled off in children and may be levelling off among younger adults (reflecting, perhaps, the systemic progress being made in recent years). [8]

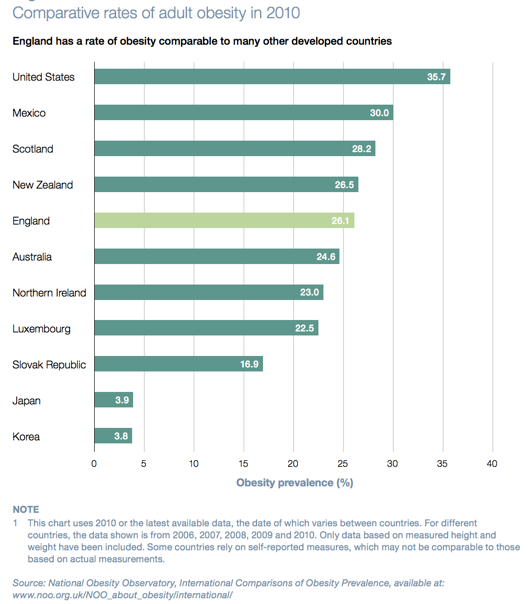

Nonetheless, the absolute level of obesity remains very high and England (along with the rest of the UK) ranks as one of the most obese nations in the world; there are no signs yet of a sustained decline, and (as obesity tends to increase with age) the UK's ageing population remains a concern.

A profound impact on the health of the population(Node #348776)Obesity is responsible for more than 9,000 premature deaths each year in England, reduces life expectancy on average by nine years, and is a major risk factor in wide range of serious health problems including Type 2 diabetes (5 x), cancer (3 x the risk of colon cancer), and heart disease (2.5 x).

Source: Public Health England [9]

Compared with a non-obese man, an obese man is:

- five times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes

- three times more likely to develop cancer of the colon

- more than two and a half times more likely to develop high blood pressure – a major risk factor for stroke and heart disease.

An obese woman, compared with a non-obese woman, is:

- almost thirteen times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes

- more than four times more likely to develop high blood pressure

- more than three times more likely to have a heart attack.

Risks of other diseases, including angina, gall bladder disease, liver disease, ovarian cancer, osteoarthritis and stroke, are also increased.

If current trends persist, one in three people will be obese by 2034 and one in ten will develop type II diabetes (Figure 9, below); whereas, reducing obesity back to 1993 levels, would avoid five million cases of disease (Figure 10, below).

Source: Public Health England [9]

- Around 58% of type 2 diabetes, 21% of heart disease and between 8% and 42% of certain cancers (endometrial, breast, and colon) are attributable to excess body fat.

- Obesity reduces life expectancy by an average 9 years and is responsible for 9,000 premature deaths a year in England.

- In addition, people who are obese can experience stigmatisation and bullying, which can lead to depression and low self-esteem. [1]

Increased risk of Type 2 diabetes (Node #352351)Obesity substantially raises the risk of Type 2 diabetes—with excess body fat estimated to underlie almost two-thirds of cases of diabetes in men and three quarters of cases in women—and people at risk of diabetes can cut their chances of getting diabetes by 60% if they lose between 5% and 7% of their body weight. Worldwide, the number of people with diabetes has tripled since 1985. [2]

Prevalence: Being overweight or obese is the main modifiable risk factor for type 2 diabetes. In England, obese adults are five times more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes than adults of a healthy weight. Currently 90% of adults with type 2 diabetes are overweight or obese. People with severe obesity are at greater risk of type 2 diabetes than obese people with a lower BMI.

Health impact: People with diabetes are at a greater risk of a range of chronic health conditions including cardiovascular disease, blindness, amputation, kidney disease and depression than people without diabetes. Diabetes leads to a two-fold excess risk for cardiovascular disease, and diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of preventable sight loss among people of working age in England and Wales. Diabetes is a major cause of premature mortality with around 23,300 additional deaths in 2010-11 in England attributed to the disease.

Economic impact: It is estimated that in 2010-11 the cost of direct patient care (such as treatment, intervention and complications) for those living with type 2 diabetes in the UK was £8.8 billion and the indirect costs (such productivity loss due to increased death and illness and the need for informal care) were approximately £13 billion. Prescribing for diabetes accounted for 9.3% of the total cost of prescribing in England in 2012-13.

Type 2 diabetes

- The underlying disorder for type 2 diabetes is usually insulin insensitivity combined with a failure of pancreatic insulin secretion to compensate for increased glucose levels. The insulin insensitivity is usually evidenced by excess body weight or obesity, and exacerbated by over-eating and inactivity.

- It is commonly associated with raised blood pressure and a disturbance of blood lipid levels. The insulin deficiency is progressive over time, leading to a need for lifestyle change often combined with blood glucose lowering therapy.

- Factors which influence someone's risk of type 2 diabetes include: weight, waist circumference, age, physical activity and whether or not they have a family history of type 2 diabetes.

- Particular conditions can increase the risk of type 2 diabetes. These include: cardiovascular disease, hypertension, obesity, stroke, polycystic ovary syndrome, a history of gestational diabetes and mental health problems. In addition, people with learning disabilities and those attending accident and emergency, emergency medical admissions units, vascular and renal surgery units and ophthalmology departments may be at high risk.

- In addition to these individual risk factors, people from certain communities and population groups are particularly at risk. This includes people of South Asian, African-Caribbean, black African and Chinese descent and those from lower socioeconomic groups.

Metabolic Syndrome

- Metabolic syndrome is a combination of disorders including high blood glucose, high blood pressure and high cholesterol and triglyderide levels, that is more common in obese individuals and is associated with significant risks of coronary heart disease and Type 2 diabetes. There is also a greater risk of dyslipidemia (for example, high total cholesterol or high levels of triglycerides), which also contributes to the risk of circulatory disease by speeding up atherosclerosis (fatty changes to the linings of the arteries).

Diabesity(Node #387636)

Diabetes caused by overweight or obesity (and synonymous with the usual form of type 2 diabetes). UCLA started a Diabesity Research Program in 1998. [4]

Increased risk of several cancers(Node #351181)The risk of several cancers is higher in obese people, including endometrial, breast and colon cancers. BMI is associated with cancer risk, with substantial population-level effects (although the heterogeneity in the effects suggests that different mechanisms are associated with different cancer sites and different patient subgroups).

- The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has found that around 7,000 male and 13,000 female cancer cases in the UK each year could be attributed to obesity –and that over four in 10 cancers in the UK could be prevented through lifestyle changes that encourage healthy eating and exercise. [5]

- Research has suggested that body-mass index (BMI) is an important predictor of cancer risk, 2 and a Norwegian cohort study reported associations with several cancer sites, including the thyroid 3 and ovaries; 4 and the UK Million Women Study showed associations between BMI and ten of 17 sites investigated.5

- Two large reviews brought these and many smaller studies together.6, 7 In a meta-analysis of 221 datasets, strong associations were recorded between BMI and cancers of the oesophagus, thyroid, colon, kidneys, endometrium, and gallbladder, and weaker associations were shown for several other sites. 7

- Increased BMI was negatively associated with lung cancer.

Increased risk of heart disease(Node #352349)

Raised BMI increases the risk of hypertension (high blood pressure), which is itself a risk factor for coronary heart disease and stroke and can contribute to other conditions such as renal failure. The risk of coronary heart disease (including heart attacks and heart failure) and stroke are both substantially increased. Risks of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism are also increased.

Increased risk of musculoskeletal disability(Node #352344)Raised body weight puts strain on the body's joints, especially the knees, increasing the risk of osteoarthritis (degeneration of cartilage and underlying bone within a joint). There is also an increased risk of low back pain.

- There is a two-way relationship between obesity and disability in adults.

- Obesity is associated with the four most prevalent disabling conditions in the UK: arthritis, back pain, mental health disorders and learning disabilities.

- One third of obese adults in England have a limiting long term illness or disability compared to a quarter of adults in the general population.

- The prevalence of obesity-related disabilities among adults is increasing.

- Adults with disabilities have higher rates of obesity than adults without disabilities.

- For those adults who are disabled and obese, social and health inequalities relating to both conditions may be compounded. This can lead to socioeconomic disadvantage and discrimination.

- The combination of rising obesity and disability has significant implications for health and social care services in England.Obesity may lead to disability as a consequence of increased body weight, associated co-morbidities, environmental factors, or a combination of these.

- Obesity places mechanical stress on joints, increasing the risk of back pain and osteoarthritis which may in turn limit mobility. Some obese people may face difficulties in performing tasks such as walking, climbing steps, driving or dressing. This in turn can lead to physical inactivity, pain and discomfort, functional limitations and mental distress.

- Older people who are obese are at particular risk of joint pain and arthritis and may be less motivated to engage in physical activity if they are concerned about falls and bone fractures.

- Among people with severe obesity, limitations in mobility-related activities have been reported to be between five and nine times greater than for healthy weight subjects.

- A recent UK cohort study of adults with severe obesity found that the prevalence of self-reported disability was strongly associated with BMI, age, the presence of type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome and clinical depression.

Increased risk of gastrointestinal disease(Node #352356)

Obesity is associated with: increased risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux and increased risk of gall stones.

Increased risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease(Node #352355)The term ‘non-alcoholic fatty liver disease’ (NAFLD) refers to a range of conditions resulting from the accumulation of fat in cells inside the liver. It is one of the commonest forms of liver disease in the UK. If left untreated, it may progress to severe forms such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis and cirrhosis. It has also been linked to liver cancer.

- Obesity is an important risk factor for the condition: over 66% of overweight people, and over 90% of obese individuals are at risk of NAFLD.

- As levels of obesity have risen, so has the prevalence of NAFLD. There is a lack of high quality data related to the prevalence of NAFLD in the UK. This is due to a number of factors including variations in diagnostic criteria, the invasive nature of diagnosis, and the lack of symptoms in people with mild forms of the condition.

- Approaches to tackling the condition focus on weight reduction through a combination of diet and physical activity, but there is no specific evidence-based treatment for NAFLD.

- Scientific understanding of the condition is limited, and there is a lack of high quality data on it. The impact of rising obesity levels on the prevalence and severity of NAFLD is not known, nor are the natural history or optimal management of the condition. There is a lack of scientific consensus on just how significant a threat to health NAFLD presents. In order to explore these issues in more detail we held an initial expert workshop in October 2013, and are continuing to develop this work in PHE and with external partners.

- Improvements in outcomes from NAFLD will require better data collection through primary and secondary care, death certification, and transplant registers, as well as research into the causes and treatment of the condition.

Increased risk of psychological and social problems(Node #352357)There are bi-directional associations between mental health problems and obesity, with levels of obesity, gender, age and socioeconomic status being key risk factors. Overweight and obese people can suffer from stress, low self-esteem, social disadvantage, depression and reduced libido.

- The mental health of women is more closely affected by overweight and obesity than that of men.

- There is strong evidence to suggest an association between obesity and poor mental health in teenagers and adults. This evidence is weaker for younger children.

- The perception of being obese appears to be more predictive of mental disorders than actual obesity in both adults and children (although the relationships between actual body weight, self-perception of weight and weight stigmatisation are complex and vary across cultures, age and ethnic groups).

- Weight stigma increases vulnerability to depression, low self-esteem, poor body image, maladaptive eating behaviours and exercise avoidance.

- There is an urgent need for evaluations of weight management interventions, both in terms of weight loss and psychological benefits.

- Intervention strategies should consider both the physical and mental health of patients. It has been recommended that care providers should monitor the weight of depressive patients and, similarly, in overweight or obese patients, mood should be monitored. This awareness could lead to prevention, early detection, and co-treatment for people at risk, ultimately reducing the burden of both conditions.

Blaming people living with obesity can be counterproductive(Node #391400)Blaming people living with obesity creates counterproductive tension between prevention and clinical care.

Increased risk of reproductive and urological problems(Node #352353)

Obesity is associated with greater risk of stress incontinence in women. Obese women are at greater risk of menstrual abnormalities, polycystic ovarian syndrome and infertility. Obese men are at higher risk of erectile dysfunction. Maternal obesity is associated with health risks for both the mother and the child and after pregnancy.

Increased risk of sleep apnoea and asthma(Node #352354)

Overweight and obese people are at increased risk of sleep apnoea (interruptions to breathing while asleep) and other respiratory problems such as asthma.

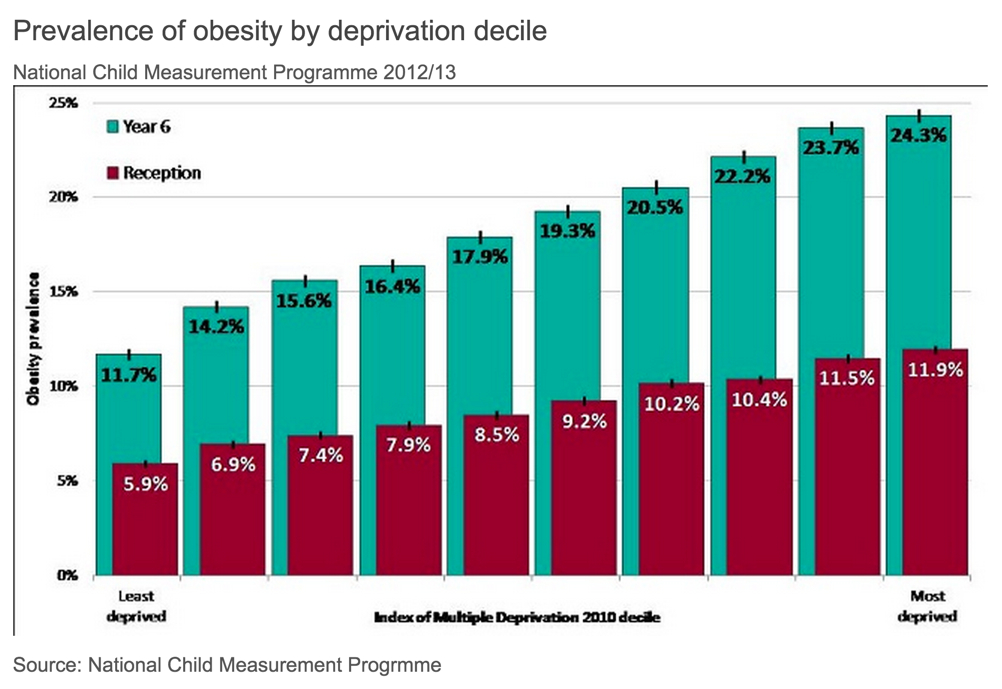

Inequality of impact(Node #351674)Although obesity occurs across all population groups, it impacts disproportionately on the socially and economically disadvantaged and some ethnic minorities. [8]

More Details – PHE Obesity >>

- Obesity is related to social disadvantage among adults [6], [8] and children [7], [8].

- It is also linked to ethnicity: it is most prevalent among African-Caribbean and Irishmen and least prevalent among Chinese women [7], [8].

Individual tragedy(Node #400252)Systemic problems like obesity involve many individual tragedies that touch many families' lives; some become symbolic of the national challenge but most are hidden in private pain and grief.

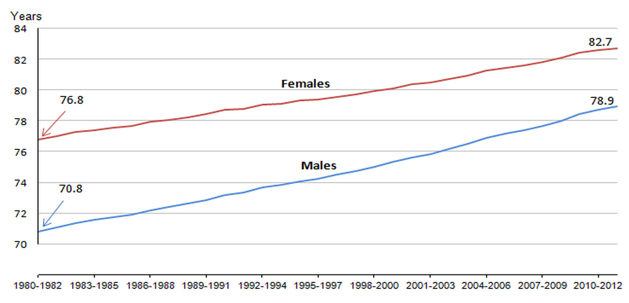

Life expectancy at birth has increased over the last 30 years(Node #371548)Life expectancy at birth, UK (1980-1982 to 2011-2013)

Source: ONS

The health consequences of rising obesity are not clear(Node #371553)

Although the incidence of overweight and obesity are increasing, the health consequences of the increasing incidence are not clear.

Body fat's role in excess mortality and morbidity remains uncertain(Node #371554)

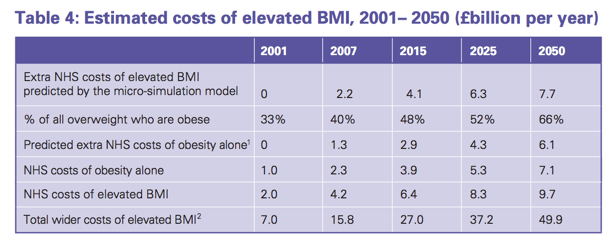

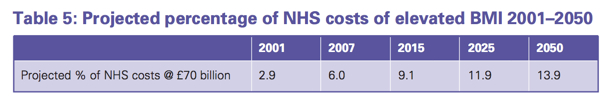

A potentially unsustainable financial burden on the health system(Node #348767)The range of obesity's impacts makes accurate economic analysis challenging; however, a November 2014 study from the McKinsey Global Institute placed the annual economic impact on the UK at around $73bn (£46bn). Earlier analysis and modelling for the 2007 Foresight Report suggested a cost to the NHS of around £4.2bn annually to treat people with health problems related to elevated BMI and a total wider cost to the economy of around £15.8bn (rising to £27bn by 2015 and £49.9bn by 2050).

Simon Stevens, Chief Executive of NHS England warned in September 2014 of the need to get serious about obesity or bankrupt the NHS (with the cost of treating the health consequences of obesity escalating as the prevalence of obesity spreads in the population):

Obesity is the new smoking, and it represents a slow-motion car crash in terms of avoidable illness and rising health care costs... If as a nation we keep piling on the pounds around the waistline, we’ll be piling on the pounds in terms of future taxes needed just to keep the NHS afloat. [13]

The McKinsey Global Institute analysis [11] found that obesity generated an economic loss in the UK of more than $70 billion a year in 2012, or 3.0 percent of GDP (see below); the second biggest impact – within the analysis as defined (covering the loss of productive life, direct health-care costs, and investment to mitigate the cost) – of 14 human generated burdens:

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

A 2010 review by the National Obesity Observatory of previous economic analyses of the burden of obesity in the UK noted: [2]

- Estimates of the direct NHS costs of treating overweight and obesity, and related morbidity in England have ranged from £479.3m in 1998 [4] to £4.2bn in 2007. [1]

- Estimates of the indirect costs (those costs arising from the impact of obesity on the wider economy such as loss of productivity) from these studies ranged between £2.6bn [4] and £15.8 billion.[1] Modelled projections suggest that indirect costs could be as much as £27bn by 2015. In 2006/07, obesity and obesity-related illness was estimated to have cost £148 million in inpatient stays in England. [10]

Source: Foresight Report, 2007

- Premature deaths attributable to obesity lead to the annual loss of around 45,000 years of working life. Sickness absence attributable to obesity is estimated at between 15.5 million and 16 million days per year.Obese people are much less likely to be in employment than those of healthy weight, with associated welfare costs estimated at between £1 billion and £6 billion. The total cost to the economy of being overweight or obese has been estimated as some £16 billion in 2007, rising to £50 billion per year by 2050 if left unchecked.

- It is estimated that 23% of spending on all drugs is attributable to overweight and obesity. The minimum annual cost of any drug prescriptions at BMI 20 rose from £50.71 for men and £62.59 for women by £5.27 and £4.20, respectively, for each unit increase in BMI to a BMI of 25.3 Increases for each BMI unit were greater to BMI 30, and greater still, £8.27 (men) and £4.95 (women), to BMI 40.

Source: Foresight Report, 2007

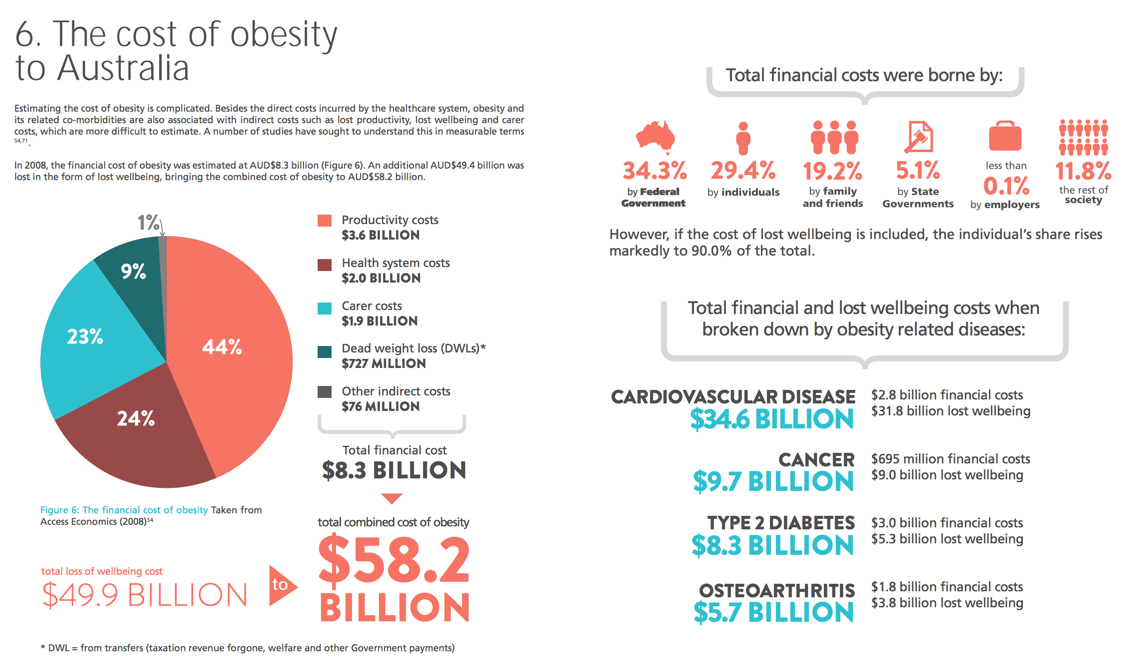

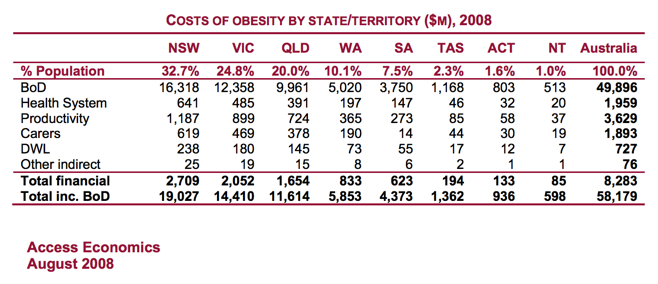

Financial cost of obesity – international comparisons(Node #370359) Financial cost of obesity – Australia(Node #362029)The overall annual cost of obesity to Australian society and governments was estimated to be $58.2 billion in 2008 – which, when adjusted for relative population, suggests that the actual overall annual cost of obesity to the UK may closer to £100m per year.

- The total direct financial cost of obesity for the Australian community was estimated to be $8.3 billion in 2008. Of these costs, the Australian Government bears over one-third (34.3% or $2.8 billion per annum), and state governments 5.1%.

- This estimate includes productivity costs of $3.6 billion (44%), including short- and long-term employment impacts, as well as direct financial costs to the Australian health system of $2 billion (24%) and carer costs of $1.9 billion (23%).

- The net cost of lost wellbeing (the dollar value of the burden of disease, netting out financial costs borne by individuals) was valued at $49.9 billion.

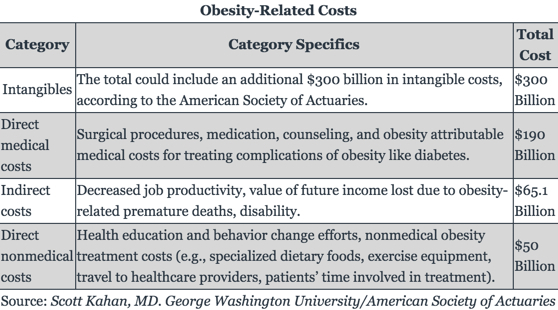

Financial cost of obesity – USA(Node #362031)Analysis [6] prepared for The Fiscal Times by Scott Kahan—director of the National Center for Weight & Wellness at George Washington University—puts the total national cost of obesity (including direct medical and non-medical services, decreased worker productivity, disability and premature death) at $305.1bn annually. Including the intangible costs associated with pain and suffering from obesity and obesity-associated conditions would add at least a further $300bn a year (Society of Actuaries).

- Direct medical costs (including counselling, outpatient and hospital visits, a range of bariatric surgical procedures, new treatment, nursing home care, rehabilitation and hospice) account for $190 billion of the annual costs. [5]

- Non-medical costs (including health education and behavioural change) add $50 billion per year.

- Absenteeism and sub-par productivity in the workplace costs an additional $65.1 billion a year.

Earlier Analysis of the Economic Impact of Obesity on the US

- In 2010, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office reported that nearly 20 percent of the increase in U.S. health care spending (from 1987-2007) was caused by obesity.

- Annual health costs related to obesity in the U.S. is nearly $200 billion, and nearly 21 percent of medical costs in the U.S. can be attributed to obesity.

- Researchers estimate that if obesity trends continue, obesity related medical costs, alone, could rise by $43 to $66 billion each year in the United States by 2030.

- Per capita medical spending is $2,741 higher for people with obesity than for normal weight individuals.

View full size >>

Obesity's Impact on the US Workforce

- Full-time workers in the U.S. who are overweight or obese and have other chronic health conditions miss an estimated 450 million additional days of work each year compared with healthy workers-- resulting in an estimated cost of more than $153 billion in lost productivity annually, according to a 2011 Gallup Poll.

- Medical expenses for obese employees are 42% than for a person with a healthy weight, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

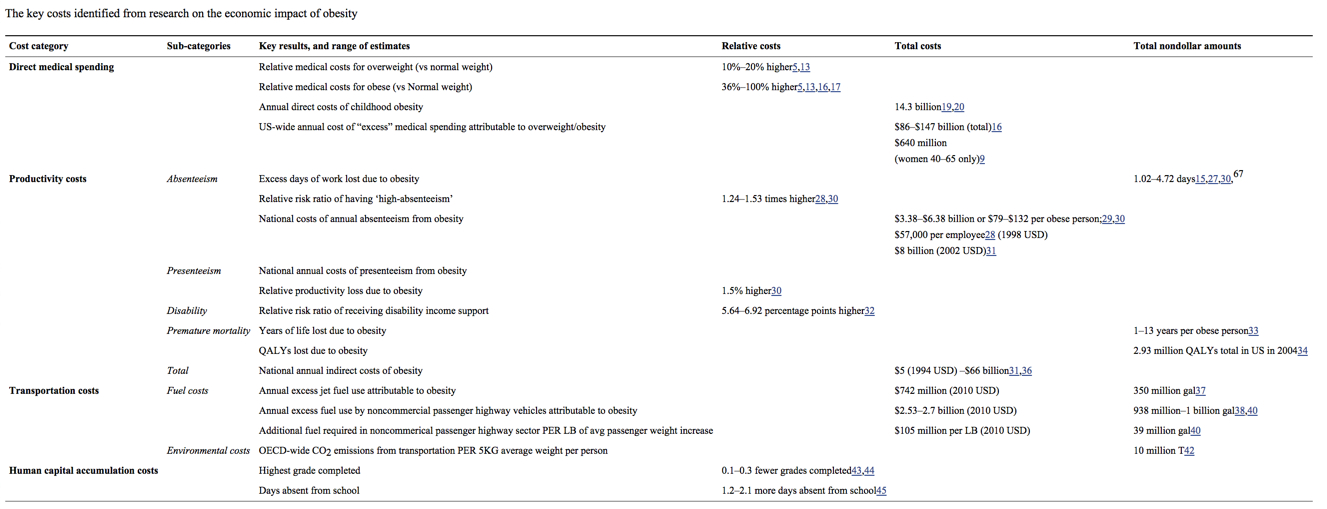

What costs should be included in the financial analysis?(Node #366990)What cost factors should be included in the assessment of the overall financial impact of obesity on the UK economy?

Direct healthcare costs of obesity(Node #362119)

The direct costs of obesity are those that result from outpatient and inpatient health services (including surgery), laboratory and radiological tests, and drug therapy. [1]

Hospital Inpatient Visits(Node #362116)

Hospital Outpatient Visits(Node #362117)

Obesity Drug Costs(Node #362118)

Obesity Research Costs(Node #362127)

Indirect financial costs of obesity(Node #362121)

The indirect costs of obesity are the resources forgone as a result of an obesity-related health condition. [1]

Lost productivity(Node #352311)Obesity has as a serious impact on UK economic development – constraining economic productivity and increasing business costs – affecting individuals’ ability to get and hold down work, their self-esteem and their underlying mental health.

Absenteeism(Node #362122)

Obese employees miss more days from work due to short-term absences and long-term disability, than nonobese employees. [2]

Early retirement(Node #362124)

Obese employees are more likely, in general, to retire early than non-obese employees.

Human capital accumulation costs(Node #362140)

Days absent from school(Node #362141)

Highest grade completed(Node #362142)

Premature mortality(Node #362125)

Premature death is more likely, in general, among obese employees than non-obese employees.

QALYs lost due to obesity(Node #362139)

Years of life lost due to obesity(Node #362138)

Presenteeism(Node #362123)

Obese employees are more likely, in general, to work at less than full capacity than non-obese employees.

Costs of carers(Node #362128)

Lost taxation(Node #362130)

Transportation costs(Node #362131)

Environmental costs(Node #362132)

OECD-wide CO2 emissions from transportation(Node #362137)

OECD-wide CO2 emissions from transportation PER 5KG average weight per person

Fuel costs(Node #362133)

Additional fuel required in noncommerical passenger highway sector(Node #362136)

Additional fuel required in noncommerical passenger highway sector PER LB of avg passenger weight increase.

Annual excess fuel use by noncommercial passenger highway vehicles(Node #362135)

Annual excess fuel use by noncommercial passenger highway vehicles attributable to obesity.

Annual excess jet fuel use attributable to obesity(Node #362134)

Welfare costs(Node #362129)

Intangible costs of obesity(Node #370536)

The intangible costs associated with pain and suffering from obesity and obesity-associated conditions.

Mitigation costs(Node #367012)

Cost implications of deeming obesity to be a disability?(Node #370904)The European Court of Justice ruled in December 2014 that if obesity could hinder "full and effective participation" at work then it could count as a disability – and be covered by the protection provided for in EU Council Directive 2000/78/EC of 27 November 2000, which establishes a general framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation, and offers protection by the prohibition of discrimination on grounds of that disability.

Clive Coleman, BBC's legal correspondent

"Today's ruling was of great interest to employers across Europe. The judgement makes no direct link between Body Mass Index and obesity, but is a powerful statement that an obese worker whose weight hinders their performance at work is entitled to disability protection.

That will mean employers must, on a case by case basis, make reasonable adjustments such as providing larger chairs or special car parking, and protect such employees from verbal harassment.

But there are wider implications. Providers of goods and services such as shops, cinemas and restaurants will also have to make reasonable adjustments for their customers, which might include things like special seating arrangements.

The key concept here is that adjustments must be "reasonable" - so it may be deemed reasonable for a Premier League football club to make two seats available for someone disabled through obesity, but not for a small, non-league club.

Obesity, particularly what is sometimes known as morbid or severe and complex obesity, can be a particularly sensitive subject.

Employers and service providers will have to take care not to make assumptions about the needs of an obese worker or customer."

How to estimate the costs?(Node #371756)

What methods can be used to estimate the financial costs of obesity?

Incidence-based estimations(Node #371766)

Incidence-based estimations follow individuals in a study population, record their healthcare expenses over time, and compare the expenses of obese individuals with those of their normal-weight counterparts.

Enables statistical adjustment for multiple causes of observed costs(Node #371768)

Difficulty of tracking costs across lifetime to identify total costs(Node #371770)

Prevalence-based estimations(Node #371759)

Identify the prevalence of diseases incurred by obese individuals, the proportion of these diseases attributable to obesity (population attributable risk, or PAR), and their associated costs (direct costs attributable to obesity = PAR x average medical expenditure among all cases).

Data is readily available(Node #371760)

Results offer a snapshot of the annual cost of obesity(Node #371761)

Risk of double counting costs(Node #371763)

The overlap between different medical conditions introduce the risk of double counting costs.

Risk of omitting emerging costs from new obesity-related diseases(Node #371765)

UK figures may substantially underestimate the cost of obesity(Node #362028)Per capita comparisons with the estimated costs of obesity in Australia and the US, for example, suggest that the current UK estimates may substantially underestimate the financial cost of obesity to the nation.

Per capita comparison with Australia's obesity cost estimates(Node #371549)

Per capita comparisons with the estimated costs of obesity in Australia suggest that the current UK estimates may substantially underestimate the financial cost of obesity to the nation.

Per capita comparisons with the US's obesity cost estimates(Node #371550)

Per capita comparisons with the estimated costs of obesity in the United States of America suggest that the current UK estimates may substantially underestimate the financial cost of obesity to the nation.

Modelling suggests the majority of UK population may be obese by 2050(Node #348775)

The prevalence of obesity in the UK more than doubled in the 25 years to 2007. In England, nearly a quarter of adults and about 10% of children were obese in 2007, with a further 20–25% of children overweight. The Foresight report extrapolated that 40% of Britons might be being obese by 2025, with Britain being a mainly obese society by 2050.

Financial cost of obesity grows as the prevalence of obesity rises(Node #371552)

The cost of treating the health consequences of obesity, and productivity losses due to obesity, increase as the prevalence of obesity spreads in the population.

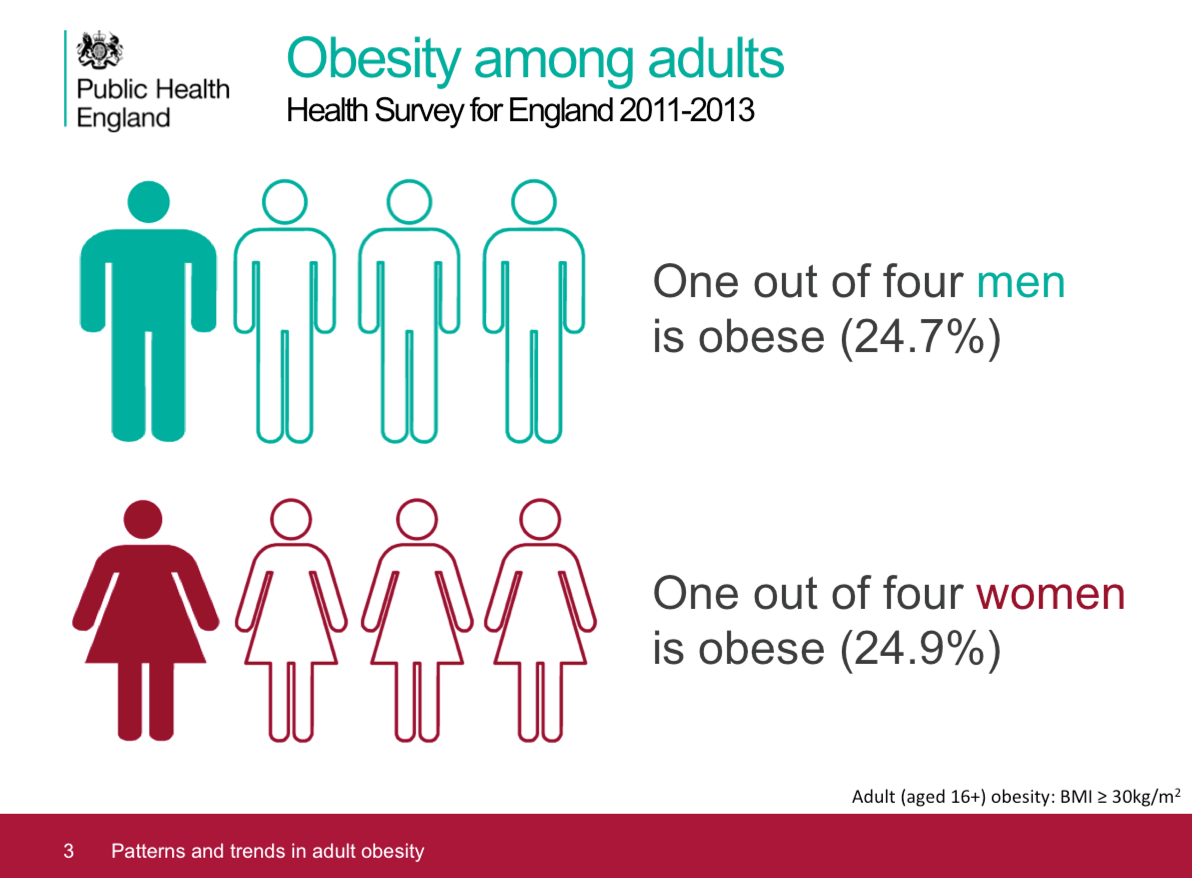

1 in 4 UK adults are obese(Node #366906)24.7 per cent of British adults are obese (compared with an average of 16.7 per cent in the rest of Europe) [1], [2] – and one out of four men (24.7%) and one of four women (24.9%) is obese in England. [4], [5]

Source: PHE Adult obesity slide set (updated March 2015) [4] 1 in 5 UK children aged 10-11 are obese(Node #352358)The National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) figures for 2013/14, show that 19.1% of children in Year 6 (aged 10-11) were obese and a further 14.4% were overweight. Obese children and adolescents are at an increased risk of developing various health problems—such as asthma, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes (as well as low self-esteem and depression)—and are also more likely to become obese adults.

- The National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) measures the height and weight of around one million school children in England every year, providing a detailed picture of the prevalence of child obesity.