|

![]()

| Not building exercise into daily life Why1 #352521 A primary cause of the rise in obesity in the UK in recent decades has been a decline in energy expended rather than rise in energy intake; with the changing pattern towards more sedentary lifestyles appearing to be a key factor in this. |

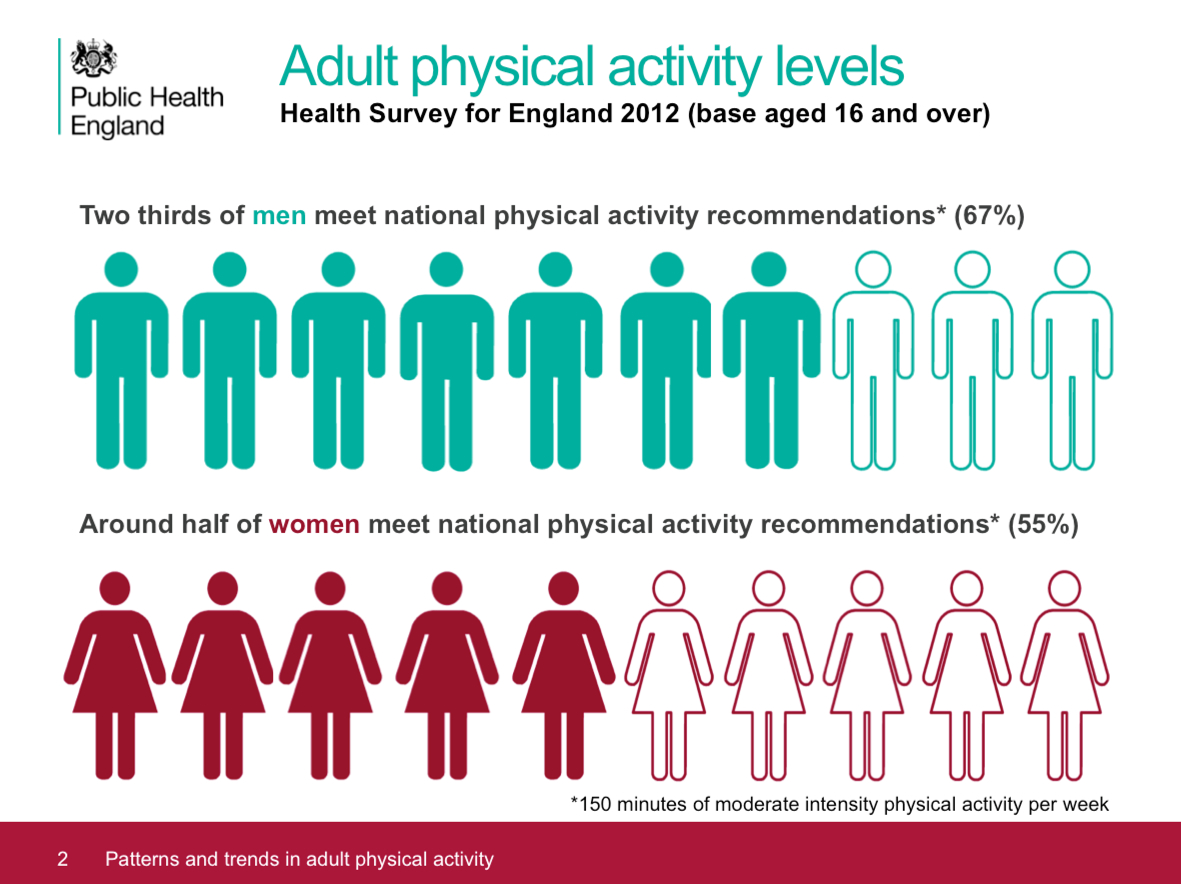

Slide: PHE Adult physical activity slide set – July 2015 [6]Around one in two women and a third of men in England are damaging their health through a lack of physical activity. [8] - over one in four women and one in five men do less than 30 minutes of physical activity a week, so are classified as ‘inactive’. [2]

- physical inactivity is the fourth largest cause of disease and disability in the UK. [7]

Snowdon [1] notes: If one looks at day-to-day exercise and occupational physical activity, it becomes clear that lifestyles have become more sedentary. The transition from manual labour to office work saw jobs in agriculture decline from eleven to two per cent of employment in the twentieth century while manufacturing jobs declined from 28 to 14 per cent of employment (Lindsay, 2003) [4]. Britons are walking less (from 255 miles per year in 1976 to 179 miles in 2010) and cycling less (from 51 miles per year in 1976 to 42 miles in 2010). Only 18 per cent of adults report doing any moderate or vigorous physical activity at work while 63 per cent never climb stairs at work and 40 per cent spend no time walking at work (British Heart Foundation, 2012b: 58-59) [3]. Outside of work, 63 per cent report spending less than ten minutes a day walking and 53 per cent do no sports or exercise whatsoever (ibid.: 52-4). Add to this the ubiquity of labour-saving devices and it is clear that Britons today have less need, and fewer opportunities, for physical activity both in the workplace and at home." |

+Citations (9) - CitationsAdd new citationList by: CiterankMapLink[1] The Fat Lie

Author: Christopher Snowdon

Publication info: 2014 August

Cited by: David Price 11:36 PM 4 January 2015 GMT

Citerank: (12) 371563Per capita sugar consumption has fallen by 16% since 1992Evidence suggests that per capita consumption of sugar, salt, fat and calories has been falling in Britain for decades. Per capita sugar consumption has fallen by 16 per cent since 1992 and per capita calorie consumption has fallen by 21 per cent since 1974.13EF597B, 371570Measuring diet at a societal level is an inexact scienceMeasuring diet at a societal level is an inexact science – as researchers generally have to rely on people keeping track of what they eat over a period of several days – and people may be inclined to under report their consumption patterns. Evidence suggests that people may throw away about 10-20% of the food they buy and underreport how much they eat by around 20–40%.8FFB597, 371611Changing patterns of physical activityTechnological development and urbanisation bring significant shifts in the patterns of daily activity that can reduce the amount of energy people expend in their normal daily routines.555CD992, 371615Self-reported physical activity is increasingThe number of people who are self-reporting as meeting the government's recommendation of taking 30 minutes vigorous exercise five times a week rose from 26.5 per cent to 37.5 per cent between 1997 and 2012. [3]13EF597B, 371616A minority of people are meeting the recommendationsAlthough the number of people self-reporting as meeting the government's recommendations is rising, the total number remains a minority of the population.13EF597B, 371617The recommendations relate only to leisure activitiesThe government recommendations, on which people are self-reporting, relate only to leisure activities – and other lifestyle factors (especially the increasingly sedentary patterns of behaviour) may be more significant in this context.13EF597B, 399908Not building exercise into daily life The primary cause of the rise in obesity in the UK in recent decades has not been a decline in energy expended rather than rise in energy intake; with the changing pattern towards more sedentary lifestyles appearing to be a key factor in this.555CD992, 399933Self-reported physical activity is increasingThe number of people who are self-reporting as meeting the government's recommendation of taking 30 minutes vigorous exercise five times a week rose rose from 26.5 per cent to 37.5 per cent between 1997 and 2012. [3]13EF597B, 399957A minority of people are meeting the recommendationsAlthough the number of people self-reporting as meeting the government's recommendations is rising, the total number remains a minority of the population.13EF597B, 399958The recommendations relate only to leisure activitiesThe government recommendations, on which people are self-reporting, relate only to leisure activities – and other lifestyle factors (especially the increasingly sedentary patterns of behaviour) may be more significant in this context.13EF597B, 399961Per capita sugar consumption has fallen by 16% since 1992Evidence suggests that per capita consumption of sugar, salt, fat and calories has been falling in Britain for decades. Per capita sugar consumption has fallen by 16 per cent since 1992 and per capita calorie consumption has fallen by 21 per cent since 1974.13EF597B, 399963Measuring diet at a societal level is an inexact scienceMeasuring diet at a societal level is an inexact science – as researchers generally have to rely on people keeping track of what they eat over a period of several days – and people may be inclined to under report their consumption patterns. Evidence suggests that people may throw away about 10-20% of the food they buy and underreport how much they eat by around 20–40%.8FFB597 URL:

| | Excerpt / Summary The rise in obesity has been primarily caused by a decline in physical activity at home and in the workplace, not an increase in sugar, fat or calorie consumption. |

Link[3] Physical Activity Statistics 2012

Author: British Heart Foundation

Publication info: 2013 June, 29

Cited by: David Price 1:35 AM 5 January 2015 GMT

Citerank: (9) 348689Encourage physical activity in daily lifeThe Chief Medical Officer’s report (2011) recommends that adults aged 19-64 years undertake 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week in bouts of 10 minutes or more. [1]565CA4D9, 348699Increasingly sedentary lifestylesSedentary behaviour is not simply a lack of physical activity but is a cluster of individual behaviours in which sitting or lying is the dominant mode of posture and energy expenditure is very low. Research suggests that sedentary behaviour is associated with poor health in all ages independent of the level of overall physical activity. Spending large amounts of time being sedentary may increase the risk of some adverse health outcomes, even among people who are active at the recommended levels.555CD992, 371611Changing patterns of physical activityTechnological development and urbanisation bring significant shifts in the patterns of daily activity that can reduce the amount of energy people expend in their normal daily routines.555CD992, 371615Self-reported physical activity is increasingThe number of people who are self-reporting as meeting the government's recommendation of taking 30 minutes vigorous exercise five times a week rose from 26.5 per cent to 37.5 per cent between 1997 and 2012. [3]13EF597B, 399668Encourage physical activity in daily lifeBuild exercise into daily life to promote energy balance. Adults are recommended to take part in 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity every week.565CA4D9, 399897Changing patterns of physical activityTechnological development and urbanisation bring significant shifts in the patterns of daily activity that can reduce the amount of energy people expend in their normal daily routines.555CD992, 399908Not building exercise into daily life The primary cause of the rise in obesity in the UK in recent decades has not been a decline in energy expended rather than rise in energy intake; with the changing pattern towards more sedentary lifestyles appearing to be a key factor in this.555CD992, 399922Increasingly sedentary lifestylesSedentary behaviour is not simply a lack of physical activity but is a cluster of individual behaviours in which sitting or lying is the dominant mode of posture and energy expenditure is very low. Research suggests that sedentary behaviour is associated with poor health in all ages independent of the level of overall physical activity. Spending large amounts of time being sedentary may increase the risk of some adverse health outcomes, even among people who are active at the recommended levels.555CD992, 399933Self-reported physical activity is increasingThe number of people who are self-reporting as meeting the government's recommendation of taking 30 minutes vigorous exercise five times a week rose rose from 26.5 per cent to 37.5 per cent between 1997 and 2012. [3]13EF597B URL:

|

Link[4] A century of labour market change: 1900 to 2000

Author: Craig Lindsay - ONS

Publication info: 2003 March, Labour Market Trends

Cited by: David Price 1:46 AM 5 January 2015 GMT

Citerank: (5) 352387Previous physical activities replaced by industrially generated energyIndustrial development allows many different aspects of life that previously involved daily physical activity to be accomplished through industrially generated energy instead; for example, the substitution of motorised transport for walking and cycling, a shift from manual and agricultural work towards office work, and a multitude of labour saving devices at work and in the home.555CD992, 371611Changing patterns of physical activityTechnological development and urbanisation bring significant shifts in the patterns of daily activity that can reduce the amount of energy people expend in their normal daily routines.555CD992, 399897Changing patterns of physical activityTechnological development and urbanisation bring significant shifts in the patterns of daily activity that can reduce the amount of energy people expend in their normal daily routines.555CD992, 399908Not building exercise into daily life The primary cause of the rise in obesity in the UK in recent decades has not been a decline in energy expended rather than rise in energy intake; with the changing pattern towards more sedentary lifestyles appearing to be a key factor in this.555CD992, 399923Previous physical activities replaced by industrially generated energyIndustrial development allows many different aspects of life that previously involved daily physical activity to be accomplished through industrially generated energy instead; for example, the substitution of motorised transport for walking and cycling, a shift from manual and agricultural work towards office work, and a multitude of labour saving devices at work and in the home.555CD992

URL:

| | Excerpt / Summary A summary of labour market conditions in the twentieth

century. |

Link[5] Obesity, Abdominal Obesity, Physical Activity, and Caloric Intake in U.S. Adults: 1988-2010

Author: Uri Ladabaum, M.S. Ajitha Mannalithara, - Parvathi A. Myer, M.H.S. Gurkirpal Singh

Publication info: 2014 February, 20, The American Journal of Medicine (2014), doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.02.026

Cited by: David Price 1:51 AM 5 January 2015 GMT

Citerank: (1) 399908Not building exercise into daily life The primary cause of the rise in obesity in the UK in recent decades has not been a decline in energy expended rather than rise in energy intake; with the changing pattern towards more sedentary lifestyles appearing to be a key factor in this.555CD992

URL:

| | Excerpt / Summary Average body-mass index (BMI) and waist circumference, obesity and abdominal obesity prevalence, and the population fraction reporting no leisure-time physical activity increased substantially in U.S. adults from 1998-2010. BMI and waist circumference trends were associated with physical activity level, but not daily caloric intake.

Although U.S. obesity rates may be stabilizing, our results lend support to the emphasis placed on physical activity in the Institute of Medicine report on Obesity. |

Link[7] UK health performance: findings of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

Author: Chritopher J.L. Murray et al.

Publication info: 2013 March, 2013, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60355-4

Cited by: David Price 4:50 PM 9 August 2015 GMT

URL:

| | Excerpt / Summary For both mortality and disability, overall health has improved substantially in absolute terms in the UK from 1990 to 2010. Life expectancy in the UK increased by 4·2 years (95% UI 4·2–4·3) from 1990 to 2010. However, the UK performed significantly worse than the EU15+ for age-standardised death rates, age-standardised YLL rates, and life expectancy in 1990, and its relative position had worsened by 2010. Although in most age groups, there have been reductions in age-specific mortality, for men aged 30–34 years, mortality rates have hardly changed (reduction of 3·7%, 95% UI 2·7–4·9). In terms of premature mortality, worsening ranks are most notable for men and women aged 20–54 years. For all age groups, the contributions of Alzheimer's disease (increase of 137%, 16–277), cirrhosis (65%, −15 to 107), and drug use disorders (577%, 71–942) to premature mortality rose from 1990 to 2010. In 2010, compared with EU15+, the UK had significantly lower rates of age-standardised YLLs for road injury, diabetes, liver cancer, and chronic kidney disease, but significantly greater rates for ischaemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lower respiratory infections, breast cancer, other cardiovascular and circulatory disorders, oesophageal cancer, preterm birth complications, congenital anomalies, and aortic aneurysm. Because YLDs per person by age and sex have not changed substantially from 1990 to 2010 but age-specific mortality has been falling, the importance of chronic disability is rising. The major causes of YLDs in 2010 were mental and behavioural disorders (including substance abuse; 21·5% [95 UI 17·2–26·3] of YLDs), and musculoskeletal disorders (30·5% [25·5–35·7]). The leading risk factor in the UK was tobacco (11·8% [10·5–13·3] of DALYs), followed by increased blood pressure (9·0 % [7·5–10·5]), and high body-mass index (8·6% [7·4–9·8]). Diet and physical inactivity accounted for 14·3% (95% UI 12·8–15·9) of UK DALYs in 2010. |

Link[9] The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases

Author: Ding Ding, Kenny D Lawson, Tracy L Kolbe-Alexander, Eric A Finkelstein, Prof Peter T Katzmarzyk, Willem van Mechelen, Michael Pratt

Publication date: 27 July 2016

Publication info: The Lancet

Cited by: David Price 4:47 PM 2 August 2016 GMT

URL:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X

| | Excerpt / Summary Background: The pandemic of physical inactivity is associated with a range of chronic diseases and early deaths. Despite the well documented disease burden, the economic burden of physical inactivity remains unquantified at the global level. A better understanding of the economic burden could help to inform resource prioritisation and motivate efforts to increase levels of physical activity worldwide.

Methods: Direct health-care costs, productivity losses, and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) attributable to physical inactivity were estimated with standardised methods and the best data available for 142 countries, representing 93·2% of the world's population. Direct health-care costs and DALYs were estimated for coronary heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, breast cancer, and colon cancer attributable to physical inactivity. Productivity losses were estimated with a friction cost approach for physical inactivity related mortality. Analyses were based on national physical inactivity prevalence from available countries, and adjusted population attributable fractions (PAFs) associated with physical inactivity for each disease outcome and all-cause mortality.

Findings: Conservatively estimated, physical inactivity cost health-care systems international $ (INT$) 53·8 billion worldwide in 2013, of which $31·2 billion was paid by the public sector, $12·9 billion by the private sector, and $9·7 billion by households. In addition, physical inactivity related deaths contribute to $13·7 billion in productivity losses, and physical inactivity was responsible for 13·4 million DALYs worldwide. High-income countries bear a larger proportion of economic burden (80·8% of health-care costs and 60·4% of indirect costs), whereas low-income and middle-income countries have a larger proportion of the disease burden (75·0% of DALYs). Sensitivity analyses based on less conservative assumptions led to much higher estimates.

Interpretation: In addition to morbidity and premature mortality, physical inactivity is responsible for a substantial economic burden. This paper provides further justification to prioritise promotion of regular physical activity worldwide as part of a comprehensive strategy to reduce non-communicable diseases. |

|

|