Conditional random fields (CRFs) are a class of statistical modelling method often applied in pattern recognition andmachine learning, where they are used for structured prediction. Whereas an ordinary classifier predicts a label for a single sample without regard to "neighboring" samples, a CRF can take context into account; e.g., the linear chain CRF popular in natural language processing predicts sequences of labels for sequences of input samples.

CRFs are a type of discriminative undirected probabilistic graphical model. It is used to encode known relationships between observations and construct consistent interpretations. It is often used for labeling or parsing of sequential data, such as natural language text or biological sequences[1] and in computer vision.[2] Specifically, CRFs find applications inshallow parsing,[3] named entity recognition[4] and gene finding, among other tasks, being an alternative to the relatedhidden Markov models. In computer vision, CRFs are often used for object recognition and image segmentation.

Description[edit]

Lafferty, McCallum and Pereira[1] define a CRF on observations  and random variables

and random variables  as follows:

as follows:

Let  be a graph such that

be a graph such that

, so that

, so that  is indexed by the vertices of

is indexed by the vertices of  . Then

. Then  is a conditional random field when the random variables

is a conditional random field when the random variables  , conditioned on

, conditioned on  , obey the Markov property with respect to the graph:

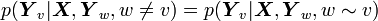

, obey the Markov property with respect to the graph:  , where

, where  means that

means that  and

and are neighbors in

are neighbors in  .

.

What this means is that a CRF is an undirected graphical model whose nodes can be divided into exactly two disjoint sets and

and  , the observed and output variables, respectively; the conditional distribution

, the observed and output variables, respectively; the conditional distribution  is then modeled.

is then modeled.

Inference[edit]

For general graphs, the problem of exact inference in CRFs is intractable. The inference problem for a CRF is basically the same as for an MRF and the same arguments hold.[5] However there exist special cases for which exact inference is feasible:

- If the graph is a chain or a tree, message passing algorithms yield exact solutions. The algorithms used in these cases are analogous to the forward-backward and Viterbi algorithm for the case of HMMs.

- If the CRF only contains pair-wise potentials and the energy is submodular, combinatorial min cut/max flow algorithms yield exact solutions.

If exact inference is impossible, several algorithms can be used to obtain approximate solutions. These include:

- Loopy belief propagation

- Alpha expansion

- Mean field inference

- Linear programming relaxations

Parameter Learning[edit]

Learning the parameters  is usually done by maximum likelihood learning for

is usually done by maximum likelihood learning for  . If all nodes have exponential family distributions and all nodes are observed during training, this optimization is convex.[5] It can be solved for example using gradient descent algorithms, or Quasi-Newton methods such as the L-BFGS algorithm. On the other hand, if some variables are unobserved, the inference problem has to be solved for these variables. Exact inference is intractable in general graphs, so approximations have to be used.

. If all nodes have exponential family distributions and all nodes are observed during training, this optimization is convex.[5] It can be solved for example using gradient descent algorithms, or Quasi-Newton methods such as the L-BFGS algorithm. On the other hand, if some variables are unobserved, the inference problem has to be solved for these variables. Exact inference is intractable in general graphs, so approximations have to be used.

Examples[edit]

In sequence modeling, the graph of interest is usually a chain graph. An input sequence of observed variables  represents a sequence of observations and

represents a sequence of observations and  represents a hidden (or unknown) state variable that needs to be inferred given the observations. The

represents a hidden (or unknown) state variable that needs to be inferred given the observations. The  are structured to form a chain, with an edge between each

are structured to form a chain, with an edge between each  and

and  . As well as having a simple interpretation of the

. As well as having a simple interpretation of the  as "labels" for each element in the input sequence, this layout admits efficient algorithms for:

as "labels" for each element in the input sequence, this layout admits efficient algorithms for:

- model training, learning the conditional distributions between the

and feature functions from some corpus of training data.

and feature functions from some corpus of training data. - inference, determining the probability of a given label sequence

given

given  .

. - decoding, determining the most likely label sequence

given

given  .

.

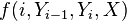

The conditional dependency of each  on

on  is defined through a fixed set of feature functions of the form

is defined through a fixed set of feature functions of the form  , which can informally be thought of as measurements on the input sequence that partially determine the likelihood of each possible value for

, which can informally be thought of as measurements on the input sequence that partially determine the likelihood of each possible value for  . The model assigns each feature a numerical weight and combines them to determine the probability of a certain value for

. The model assigns each feature a numerical weight and combines them to determine the probability of a certain value for  .

.

Linear-chain CRFs have many of the same applications as conceptually simpler hidden Markov models (HMMs), but relax certain assumptions about the input and output sequence distributions. An HMM can loosely be understood as a CRF with very specific feature functions that use constant probabilities to model state transitions and emissions. Conversely, a CRF can loosely be understood as a generalization of an HMM that makes the constant transition probabilities into arbitrary functions that vary across the positions in the sequence of hidden states, depending on the input sequence.

Notably in contrast to HMMs, CRFs can contain any number of feature functions, the feature functions can inspect the entire input sequence  at any point during inference, and the range of the feature functions need not have a probabilistic interpretation.

at any point during inference, and the range of the feature functions need not have a probabilistic interpretation.

Higher-order CRFs and semi-Markov CRFs[edit]

CRFs can be extended into higher order models by making each  dependent on a fixed number

dependent on a fixed number  of previous variables

of previous variables  . Training and inference are only practical for small values of

. Training and inference are only practical for small values of  (such as o ≤ 5),[citation needed] since their computational cost increases exponentially with

(such as o ≤ 5),[citation needed] since their computational cost increases exponentially with  . Large-margin models for structured prediction, such as the structured Support Vector Machine can be seen as an alternative training procedure to CRFs.

. Large-margin models for structured prediction, such as the structured Support Vector Machine can be seen as an alternative training procedure to CRFs.

There exists another generalization of CRFs, the semi-Markov conditional random field (semi-CRF), which models variable-length segmentations of the label sequence  .[6] This provides much of the power of higher-order CRFs to model long-range dependencies of the

.[6] This provides much of the power of higher-order CRFs to model long-range dependencies of the  , at a reasonable computational cost.

, at a reasonable computational cost.

Software[edit]

This is a partial list of software that implement generic CRF tools.