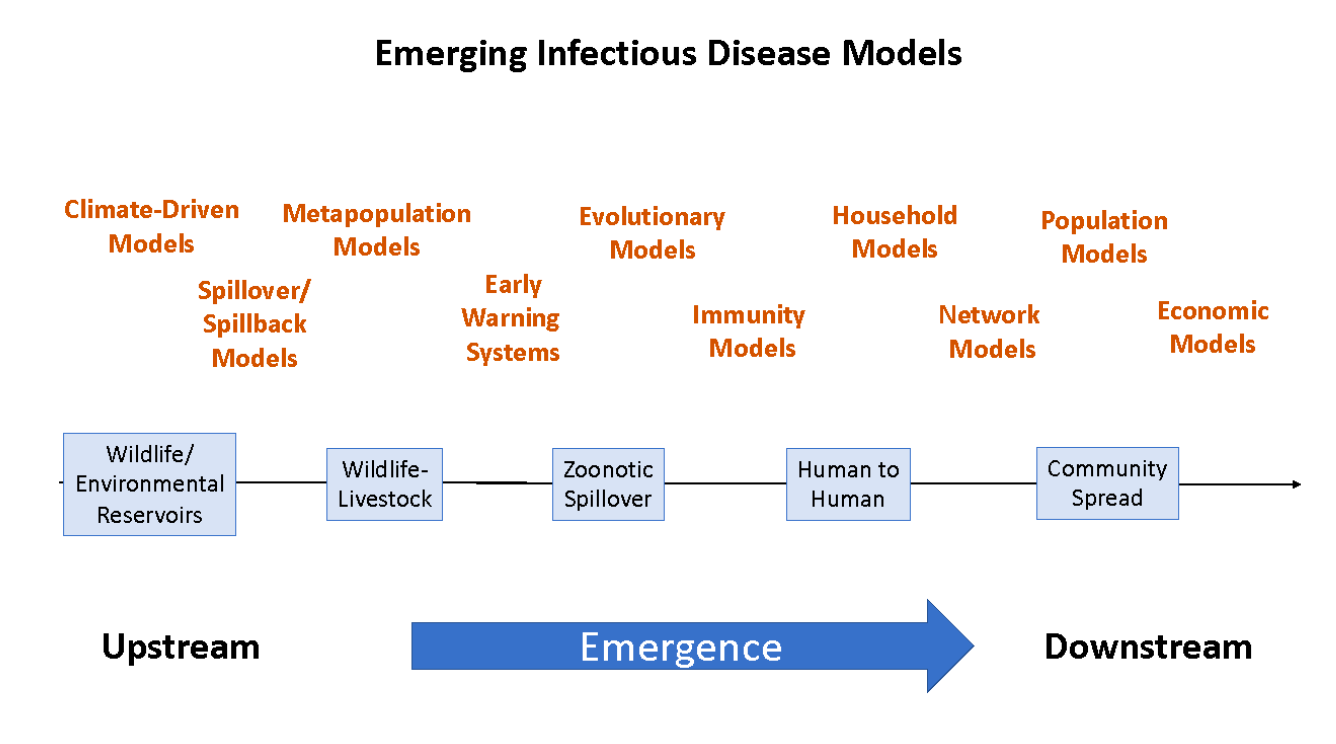

Figure 2. Emerging infectious disease models from emergence to economics.

When the pandemic hit Canada in March of 2020, there was a desperate need from public health decision-makers for information about what might happen, and the outcomes associated with possible responses. Those working in infectious disease modelling jumped to answer these questions but found that they could not work in isolation. By seeking input from colleagues working in disparate areas – epidemiology, immunology, virology, health, economics, sociology – they were able to make more sophisticated models and to answer more complicated questions. Issues raised by different jurisdictions—territorial, regional, provincial, federal—led to development of more targeted models addressing local conditions and concerns.

Interactions between modellers led to sharing of techniques and avoidance of duplication, as well as the development of a dynamic knowledge graph (http://eidm-mmie.net), which became a resource for finding expertise.

Recognizing the need for modelling efforts, the Emerging Infectious Disease Modelling (EIDM) program was created through a joint effort between PHAC and NSERC in 2021. There are now well over 100 primary investigators from across Canada who are part of this program through the network structure. The EIDM program has provided funding of $10M over two years to five key networks: Mathematics for Public Health (http://www.fields.utoronto.ca/activities/public-health), Canadian Network for Modelling Infectious Disease (https://canmod.net/), Statistical Methods for Managing Emerging Infectious Diseases (https://www.cghr.org/projects/statistical-methods-for-managing-emerging-infectious-diseases/), One Health Modelling Network for Emerging Infections (focusing on human-wildlife-domestic animal disease, https://omni-reunis.ca/), and the One Society Network (mathematical modelling of multi-sectoral impact of pandemics and control policies, https://onesocietynetwork.ca/). With a one-year, no-cost extension in place, the networks in this program are now entering their final year of funding.

The EIDM program has fostered linkages between academic teams, Indigenous groups, government organizations, as well as experts in several non-health sectors (e.g., agriculture, education), both within and outside the modelling community. Having these partnerships in place has reduced the length of the chain between modellers and policymakers, allowing for more rapid response to decision-maker needs. The past three years of collaboration has also established an environment of trust between the EIDM community and these partners. Such groups across Canada, including, for example the National Advisory Committee on Immunization, Health Canada, and PHAC, continue to turn to the EIDM program with their policy and research questions. The values and objectivity of the EIDM program meant these are open and transparent collaborations, where results are presented publicly and are open to criticism and commentary. These collaborations have also spurred research partnerships outside of infectious disease, including research into homeless populations and supply chain management (http://www.scanhealth.ca).

Building Canada’s knowledge capacity by training a new generation of researchers and practitioners is a key objective of the EIDM program. The large majority of the EIDM budget has gone to salaries for Highly Qualified Personnel (HQP)s. Trainees were attracted to the network s’ links with the government, and the potential for having an impact on Canada’s COVID-19 response. The networks recruited a very strong cohort of trainees from a range of academic backgrounds, many of whom belong to groups under-represented in the mathematical sciences. Several of these have since been employed as infectious disease modelling specialists in public health agencies and/or as university faculty. Network members integrated infectious disease modelling into their graduate and undergraduate teaching, in one case developing an upper-year undergraduate course dedicated to methods for emerging infectious disease management. Short courses on advanced topics in infectious disease modelling, such as one-health approaches, were delivered to a broad range of attendees.

The research generated by the EIDM program has resulted in an arsenal of new models (Figure 2), including compartmental epidemiological models to evaluate jurisdictions of different size and populations with different characteristics (e.g., vulnerable populations) (Wang et al. 2022; Hurford et al. 2023), in-host models to evaluate immunity, seroprevelance models to evaluate protective effects in individuals (Dick et al. 2021)), contact-mixing models to assess different feasible combinations of social distancing measures (McCarthy et al. 2020), and new models associated with emerging data (e.g., genome sequencing; pathogen sequences and concentrations in wastewater) (Nourbakhsh et al. 2022; Dean et al. 2023). Important features include sub-models for evolution (Day et al. 2020, Day et al. 2022) and competition of multiple variants, and sub-models for waning immunity from both infections and vaccinations (Childs et al. 2022; Dick et al. 2021; Korosec et al. 2022; Korosec et al. 2022; Farhang-Sardroodi et al. 2021). The EIDM networks have also been central in the development of hybrid epidemiologic-economic models that more completely assess the health impacts, costs, and trade-offs inherent in alternative policy options (Mulberry et al. 2021; Cotton et al. 2022). Some of these tools have been incorporated into provincial and federal pipelines that connect data collection to policy options. The partnerships that emerged from undertaking collaborative research with public health and health agencies and between researchers in different disciplines made the science better. While focused on COVID-19, research from the EIDM program has also provided significant new insights regarding other emerging diseases such as the 2022 outbreak of mpox (formerly monkeypox) (Yuan et al. 2023; Yuan et al. 2022c).

Funding for EIDM networks has facilitated the creation of research infrastructure that, with continued support, could continue to serve the public health community in Canada going forward. The goal of the EIDM projects was to support and promote research and public health service by EID modellers––as opposed to supporting specific research agendas as typically funded by tri-council grants––and could not have been envisioned without substantial, dedicated support for EIDM. For example, one of the EIDM networks (CANMOD) has so far scanned, digitized, and cleaned all the weekly historical infectious disease notification data from Canadian provinces and territories for the period from 1924 to 2000, much of which was handwritten. These data can now be used to test modelling methodologies on historical epidemics. Other infrastructure includes a suite of R packages for visualization and analysis including an R interface for constructing and fitting complex compartmental epidemiological models without having to code many of the details (https://mac-theobio.github.io/McMasterPandemic/). This software is used by the Public Health Agency of Canada for its regular COVID-19 forecasts, as well as for modelling other emerging diseases, such as mpox, avian influenza and pandemic influenza.

Researchers from the EIDM networks have been consulted by a variety of public health and health organisations to use their modelling expertise to quickly answer urgent questions during the COVID-19 crisis. They volunteered their time in response to the emergency and engaged extensively in public outreach efforts. The funding for the EIDM network allowed researchers to support postdocs and graduate students and to dedicate the time needed to answer the urgent questions. For example, one researcher writes:

While unfunded and volunteering my time, I co-authored a technical report (later published as (Hurford et al. 2021)) that was included in witness testimony when Newfoundland and Labrador’s travel restrictions were challenged in provincial court. It was only through funding from the EIDM program that I was able to recover my research career from this voluntary time investment.

— Dr. Amy Hurford, Memorial University.

As a group of networks, there is a potential for long-lasting impact through maintaining and growing the infrastructure of people, partnerships, innovative research, data curation and advanced modelling tools that have been developed.