This article is about decision trees in machine learning. For the use of the term in decision analysis, see

Decision tree.

Decision tree learning uses a decision tree as a predictive model which maps observations about an item to conclusions about the item's target value. It is one of the predictive modelling approaches used in statistics, data mining and machine learning. More descriptive names for such tree models are classification trees or regression trees. In these tree structures, leavesrepresent class labels and branches represent conjunctions of features that lead to those class labels.

In decision analysis, a decision tree can be used to visually and explicitly represent decisions and decision making. In data mining, a decision tree describes data but not decisions; rather the resulting classification tree can be an input for decision making. This page deals with decision trees in data mining.

General[edit]

A tree showing survival of passengers on the

Titanic ("sibsp" is the number of spouses or siblings aboard). The figures under the leaves show the probability of survival and the percentage of observations in the leaf.

Decision tree learning is a method commonly used in data mining.[1] The goal is to create a model that predicts the value of a target variable based on several input variables. An example is shown on the right. Each interior node corresponds to one of the input variables; there are edges to children for each of the possible values of that input variable. Each leaf represents a value of the target variable given the values of the input variables represented by the path from the root to the leaf.

A decision tree is a simple representation for classifying examples. Decision tree learning is one of the most successful techniques for supervised classification learning. For this section, assume that all of the features have finite discrete domains, and there is a single target feature called the classification. Each element of the domain of the classification is called a class. A decision tree or a classification tree is a tree in which each internal (non-leaf) node is labeled with an input feature. The arcs coming from a node labeled with a feature are labeled with each of the possible values of the feature. Each leaf of the tree is labeled with a class or a probability distribution over the classes.

A tree can be "learned" by splitting the source set into subsets based on an attribute value test. This process is repeated on each derived subset in a recursive manner called recursive partitioning. The recursion is completed when the subset at a node has all the same value of the target variable, or when splitting no longer adds value to the predictions. This process of top-down induction of decision trees (TDIDT) [2] is an example of a greedy algorithm, and it is by far the most common strategy for learning decision trees from data.

In data mining, decision trees can be described also as the combination of mathematical and computational techniques to aid the description, categorisation and generalisation of a given set of data.

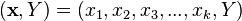

Data comes in records of the form:

The dependent variable, Y, is the target variable that we are trying to understand, classify or generalize. The vector x is composed of the input variables, x1, x2, x3 etc., that are used for that task.

Decision trees used in data mining are of two main types:

- Classification tree analysis is when the predicted outcome is the class to which the data belongs.

- Regression tree analysis is when the predicted outcome can be considered a real number (e.g. the price of a house, or a patient’s length of stay in a hospital).

The term Classification And Regression Tree (CART) analysis is an umbrella term used to refer to both of the above procedures, first introduced by Breiman et al.[3] Trees used for regression and trees used for classification have some similarities - but also some differences, such as the procedure used to determine where to split.[3]

Some techniques, often called ensemble methods, construct more than one decision tree:

- Bagging decision trees, an early ensemble method, builds multiple decision trees by repeatedly resampling training data with replacement, and voting the trees for a consensus prediction.[4]

- A Random Forest classifier uses a number of decision trees, in order to improve the classification rate.

- Boosted Trees can be used for regression-type and classification-type problems.[5][6]

- Rotation forest - in which every decision tree is trained by first applying principal component analysis (PCA) on a random subset of the input features.[7]

Decision tree learning is the construction of a decision tree from class-labeled training tuples. A decision tree is a flow-chart-like structure, where each internal (non-leaf) node denotes a test on an attribute, each branch represents the outcome of a test, and each leaf (or terminal) node holds a class label. The topmost node in a tree is the root node.

There are many specific decision-tree algorithms. Notable ones include:

- ID3 (Iterative Dichotomiser 3)

- C4.5 (successor of ID3)

- CART (Classification And Regression Tree)

- CHAID (CHi-squared Automatic Interaction Detector). Performs multi-level splits when computing classification trees.[8]

- MARS: extends decision trees to better handle numerical data.

ID3 and CART were invented independently at around same time (b/w 1970-80), yet follow a similar approach for learning decision tree from training tuples.

Formulae[edit]

Algorithms for constructing decision trees usually work top-down, by choosing a variable at each step that best splits the set of items.[9] Different algorithms use different metrics for measuring "best". These generally measure the homogeneity of the target variable within the subsets. Some examples are given below. These metrics are applied to each candidate subset, and the resulting values are combined (e.g., averaged) to provide a measure of the quality of the split.

Gini impurity[edit]

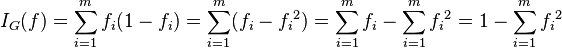

Used by the CART (classification and regression tree) algorithm, Gini impurity is a measure of how often a randomly chosen element from the set would be incorrectly labeled if it were randomly labeled according to the distribution of labels in the subset. Gini impurity can be computed by summing the probability of each item being chosen times the probability of a mistake in categorizing that item. It reaches its minimum (zero) when all cases in the node fall into a single target category.

To compute Gini impurity for a set of items, suppose i takes on values in {1, 2, ..., m}, and let fi be the fraction of items labeled with value i in the set.

Information gain[edit]

Used by the ID3, C4.5 and C5.0 tree-generation algorithms. Information gain is based on the concept of entropy frominformation theory.

Decision tree advantages[edit]

Amongst other data mining methods, decision trees have various advantages:

- Simple to understand and interpret. People are able to understand decision tree models after a brief explanation.

- Requires little data preparation. Other techniques often require data normalisation, dummy variables need to be created and blank values to be removed.

- Able to handle both numerical and categorical data. Other techniques are usually specialised in analysing datasets that have only one type of variable. (For example, relation rules can be used only with nominal variables while neural networks can be used only with numerical variables.)

- Uses a white box model. If a given situation is observable in a model the explanation for the condition is easily explained by boolean logic. (An example of a black box model is an artificial neural network since the explanation for the results is difficult to understand.)

- Possible to validate a model using statistical tests. That makes it possible to account for the reliability of the model.

- Robust. Performs well even if its assumptions are somewhat violated by the true model from which the data were generated.

- Performs well with large datasets. Large amounts of data can be analysed using standard computing resources in reasonable time.

Limitations[edit]

- The problem of learning an optimal decision tree is known to be NP-complete under several aspects of optimality and even for simple concepts.[10][11] Consequently, practical decision-tree learning algorithms are based on heuristics such as the greedy algorithm where locally-optimal decisions are made at each node. Such algorithms cannot guarantee to return the globally-optimal decision tree.

- Decision-tree learners can create over-complex trees that do not generalise well from the training data. (This is known as overfitting.[12]) Mechanisms such as pruning are necessary to avoid this problem.

- There are concepts that are hard to learn because decision trees do not express them easily, such as XOR, parity ormultiplexer problems. In such cases, the decision tree becomes prohibitively large. Approaches to solve the problem involve either changing the representation of the problem domain (known as propositionalisation)[13] or using learning algorithms based on more expressive representations (such as statistical relational learning or inductive logic programming).

- For data including categorical variables with different numbers of levels, information gain in decision trees is biased in favor of those attributes with more levels.[14]

Extensions[edit]

Decision graphs[edit]

In a decision tree, all paths from the root node to the leaf node proceed by way of conjunction, or AND. In a decision graph, it is possible to use disjunctions (ORs) to join two more paths together using Minimum message length (MML).[15]Decision graphs have been further extended to allow for previously unstated new attributes to be learnt dynamically and used at different places within the graph.[16] The more general coding scheme results in better predictive accuracy and log-loss probabilistic scoring.[citation needed] In general, decision graphs infer models with fewer leaves than decision trees.

Alternative search methods[edit]

Evolutionary algorithms have been used to avoid local optimal decisions and search the decision tree space with little a priori bias.[17][18]

It is also possible for a tree to be sampled using MCMC in a bayesian paradigm.[19]

The tree can be searched for in a bottom-up fashion.[20]

See also[edit]

Implementations[edit]

- Weka, a free and open-source data mining suite, contains many decision tree algorithms

- Orange, a free data mining software suite, module orngTree

- KNIME

- Microsoft SQL Server [1]

- scikit-learn, a free and open-source machine learning library for the Python programming language.

- R, an open source software environment for statistical computing which includes several CART implementations such as rpart, party and randomForest packages.

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Rokach, Lior; Maimon, O. (2008). Data mining with decision trees: theory and applications. World Scientific Pub Co Inc.ISBN 978-9812771711.

- Jump up^ Quinlan, J. R., (1986). Induction of Decision Trees. Machine Learning 1: 81-106, Kluwer Academic Publishers

- ^ Jump up to:a b Breiman, Leo; Friedman, J. H., Olshen, R. A., & Stone, C. J. (1984). Classification and regression trees. Monterey, CA: Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole Advanced Books & Software. ISBN 978-0-412-04841-8.

- Jump up^ Breiman, L. (1996). Bagging Predictors. "Machine Learning, 24": pp. 123-140.

- Jump up^ Friedman, J. H. (1999). Stochastic gradient boosting. Stanford University.

- Jump up^ Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., Friedman, J. H. (2001). The elements of statistical learning : Data mining, inference, and prediction. New York: Springer Verlag.

- Jump up^ Rodriguez, J.J. and Kuncheva, L.I. and Alonso, C.J. (2006), Rotation forest: A new classifier ensemble method, IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 28(10):1619-1630.

- Jump up^ Kass, G. V. (1980). "An exploratory technique for investigating large quantities of categorical data". Applied Statistics 29(2): 119–127. doi:10.2307/2986296. JSTOR 2986296.

- Jump up^ Rokach, L.; Maimon, O. (2005). "Top-down induction of decision trees classifiers-a survey". IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C 35 (4): 476–487. doi:10.1109/TSMCC.2004.843247.

- Jump up^ Hyafil, Laurent; Rivest, RL (1976). "Constructing Optimal Binary Decision Trees is NP-complete". Information Processing Letters 5 (1): 15–17. doi:10.1016/0020-0190(76)90095-8.

- Jump up^ Murthy S. (1998). Automatic construction of decision trees from data: A multidisciplinary survey. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery

- Jump up^ Principles of Data Mining. 2007. doi:10.1007/978-1-84628-766-4. ISBN 978-1-84628-765-7. edit

- Jump up^ Horváth, Tamás; Yamamoto, Akihiro, eds. (2003). Inductive Logic Programming. Lecture Notes in Computer Science2835. doi:10.1007/b13700. ISBN 978-3-540-20144-1. edit

- Jump up^ Deng,H.; Runger, G.; Tuv, E. (2011). "Bias of importance measures for multi-valued attributes and solutions". Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks (ICANN). pp. 293–300.

- Jump up^ http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu/oliver93decision.html

- Jump up^ Tan & Dowe (2003)

- Jump up^ Papagelis A., Kalles D.(2001). Breeding Decision Trees Using Evolutionary Techniques, Proceedings of the Eighteenth International Conference on Machine Learning, p.393-400, June 28-July 01, 2001

- Jump up^ Barros, Rodrigo C., Basgalupp, M. P., Carvalho, A. C. P. L. F., Freitas, Alex A. (2011). A Survey of Evolutionary Algorithms for Decision-Tree Induction. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Part C: Applications and Reviews, vol. 42, n. 3, p. 291-312, May 2012.

- Jump up^ Chipman, Hugh A., Edward I. George, and Robert E. McCulloch. "Bayesian CART model search." Journal of the American Statistical Association 93.443 (1998): 935-948.

- Jump up^ Barros R. C., Cerri R., Jaskowiak P. A., Carvalho, A. C. P. L. F., A bottom-up oblique decision tree induction algorithm. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications (ISDA 2011).

External links[edit]