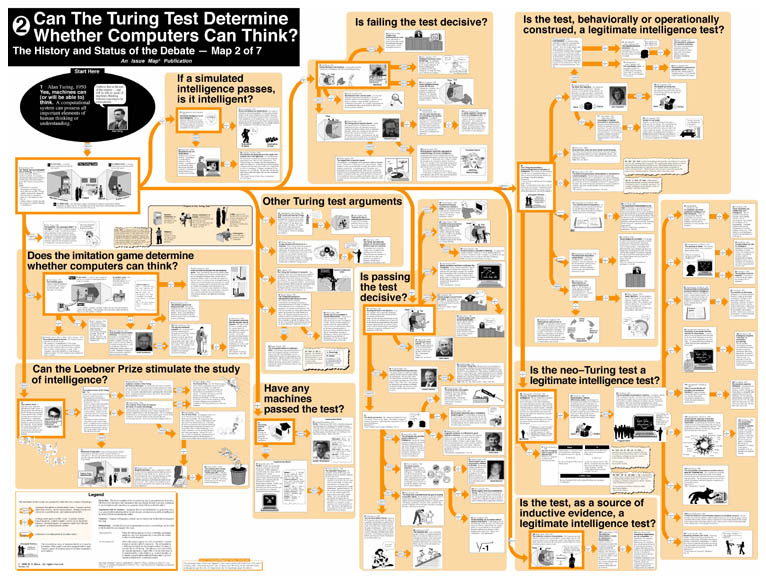

Can the Turing Test determine this? [2]

Is the Turing Test—proposed by Alan Turing in 1950—an adequate test of thinking? Can it determine whether a machine can think? If a computer passess the test by persuading judges via a teletyped conversation that it's human can it be said to think?

[[

A full-sized version of the original can be ordered here.

The questions explored on Map 2 – Can the Turing Test determine whether computers can think? are:

- Is failing the test decisive?

- Is passing the test decisive?

- If a simulated intelligence passes, is it intelligent?

- Have any machines passed the test?

- Is the test, behaviorally or operationally construed, a legitimate intelligence test?

- Is the test, as a source of inductive evidence, a legitimate intelligence test?

- Is the neo-Turing test a legitimate intelligence test?

- Does the imitation game determine whether computers can think?

- Can the Loebner Prize stimulate the study of intelligence?

- Other Turing test arguments

]]

Background

Turing argued that the question "can machines think?" is too vague—that it cannot be decided by asking what these words commonly mean, because that reduces the question of machine intelligence to a statistical survey like the Gallup Poll.

Hence the question "can machines think?" should be replaced by the more precise question of whether they can pass the Turing test.

"I propose to consider the question, 'Can machines think?' This should begin with definitions of the meaning of terms 'machine' and 'think'. The definitions might be framed so as to reflect so far as possible the normal use of the words, but this attitude is dangerous. If the meaning of the words 'machine' and 'think' are to be found by examining how they are commonly used it is difficult to escape the conclusion that the meaning and the answer to the question, 'Can machines think?' is to be sought in a statistical survey such as a Gallup poll. But this is absurd. Instead of attempting such a definition I shall replace the question by another, which is closely related to it and is expressed in relatively unambiguous words"

Turing, A.M. (1950, p,40) "Computing Machinery and Intelligence" in Boden. M. ed. The Philosophy of Artificial Intelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Turing goes on to describe the imitation game, which has evolved into what is known as the Turing Test.

The Turing TestIn the standard version of the test, an interrogator in one room (observed by judges and a referee, engages in teletyped (computer) conversation with a human control contestant in a second room and a machine contestant in a third room. If the machine can trick the interrogator and the judges into thinking it is a human, the machine has passed the Turing Test.

The Players

Authors differ in whether they take the Turing Test to establish 'thinking' or 'intelligence'.

Other variations of the test are possible.